01/2020

Grasshopper Film

Single Take: Lynne Sachs on Jean-Luc Godard

Having just completed her new documentary, Film About a Father Who, Lynne Sachs reflects on the decades-long impact Godard has had on her creative process, recalling first-time viewings of Vivre Sa Vie, Notre Musique, and others, in this Single Take.

As much I call myself a cinéphile, there are certain times in my filmmaking process — be it the production or post-production phase — when I try not to watch anything that is not going to help me strategize on how to solve a particular obstacle in front of me. Once I’ve found a solution to the problem at hand, I hop back into theaters with anticipation and abandon.

When I read Martin Scorsese’s “The Dying Art of Filmmaking” in The New York Times this past November, I felt I’d come upon an awkwardly realized epiphany, the fraught words of a man who had reached the pinnacle of critical and commercial success, only to recognize the blanket banality of the nirvana on which he had landed. “Cinema is an art form that brings you the unexpected. In superhero movies, nothing is at risk,” he laments. It’s not just the characters who should be on an adventure. It’s the filmmaker as well. Whether in front or behind the camera, Scorsese seems to be saying that you must have the sensation of being fragile, caught in the conundrum of possible failure.

With this said, I choose to write about the enfant terrible, the angry old man, the sixty-year trendsetter for all things cinema, Jean-Luc Godard. The first Godard film I remember seeing was his 1962 episodically constructed fiction film Vivre Sa Vie. It was the mid-1980s, and I was in graduate school in the Cinema Department at San Francisco State University, shooting my first 16mm film, Still Life with Woman and Four Objects (1987). In that mysterious way that great teachers can connect with their students, a professor loaned me his VHS copy of Godard’s film. He simply informed me that he thought I would like it, and he was right. At its crux, this is why we go to graduate school, to find those kindred spirits who claim to know us better than we know ourselves. I watched this brazen yet delicate narrative film on a young mother who gives up her husband and family to find her independence, moving from acting to retail work to prostitution, and in the process immersing herself in her own epistemological inquiries. While I quickly realized that Godard as director was simultaneously constructing and destroying Nana’s place in the world in which she lives, I saw in his radical methodologies a language that offered viewers the opportunity to examine the meaning of the images and sounds in a film in new, revealing ways. In my four-minute Still Life, I too wanted to deconstruct (a popular word at that time) the apparatus of cinema. Ambitious, heady, and scared, I experimented with using fiction and documentary simultaneously. Unbeknownst to Monsieur Godard, he had given me a kernel of artistic confidence. Risk became my task and not my nemesis.

On a November morning in 2002, I sat down to read The New York Times. To my shock, I came across the story of an Israeli filmmaker and teacher who was killed along with her two sons on a kibbutz near the West Bank. In so many ways, her work and life paralleled my own as a filmmaker and new mother. I immediately contacted a former film student of mine, an Israeli, explaining to him that I wanted to make a movie about this woman but that I was not in a position to fly to the Middle East to shoot the project. My reasons were two-fold. First of all, I was disturbed by Israeli political actions in the West Bank and wanted to follow the exigencies of French feminist Hélene Cixous: “I am on the side of Moses, the one who does not enter…. ‘Next year, in Jerusalem’ makes me flee.” Second, having lived in New York City during September 11, 2001, and its aftermath, I still felt too unsettled to travel to another place on the globe where violence seemed to run rampant. I was scared. This was a physical risk I was not yet prepared to take. My 2005 States of UnBelonging was propelled by my effort at making an anti-documentary. Unlike most people in the field, I didn’t want to see, hear, or smell for myself. I wanted to rely on my imagination and on the mediation of others, be they amateur or professional.

During the last few months of editing this film, I watched Godard’s Notre Musique (2004) at New York City’s Film Forum. This film is an expansive, essayistic cinémeditation on the seemingly never-ending antagonism between Palestinians and Israelis. Throughout his epic political treatise — fraught with ambiguity, anguish, and outright anger – Godard dares to infuse his exposition on war with abstracted, richly colored, high-contrast images. These gestural arabesques transform the geographic specificity of his discussion into a choreographed dreamscape. As a viewer sitting in the dark, I felt a free-floating delight that I had never before experienced. While the “subject” was harrowing, the sensations were joyous; and yet I knew that this departure from the gravitas of the film’s thematic anchor was complicated. Once again, my “mentor” was giving me license to take similar formal leaps in my own film. The first few minutes of States of UnBelonging comprise highly solarized fragments from mainstream news material shot at and near the infamous wall dividing the Palestinian Territories from Israel. I used mostly primary colors that seemed to erase skin differences, making it almost impossible to tell which bodies were associated with a particular side of the controversy. For a moment, viewers don’t know which “side” they are on, politically or geographically. In this context, ambiguity itself becomes unsettling and, perhaps, risky.

Between 2007 and 2009, I watched a range of films including Rome, Open City by Robert Rossellini, The Garden of the Finzi Continis by Vittorio de Sica, Friendship’s Death by Peter Wollen, and Fanny and Alexander by Ingmar Bergman as research for the making of my 2009 film The Last Happy Day. While historically and thematically relevant to my film’s “subject,” none of these remarkable works helped me figure out one particularly challenging conundrum.

The Last Happy Day is an experimental portrait of Sandor Lenard, a distant cousin of mine whom I actually never met. During WWII, Sandor devised his own way to survive the traumatic world of Nazi-occupied Rome in the 1940s. As a struggling doctor with Jewish lineage, he worked for the United States Army reconstructing the bodies of soldiers killed by military explosions. After the war, Sandor, a brilliant stateless polyglot, ran as far as he could from the devastation of the war. He moved to Brazil where he taught Latin to children, and, in the process, threw himself into a seemingly ridiculous language experiment, the translation of the English Winnie the Pooh into the Latin Winnie Ille Pu. Surprisingly, the manuscript’s publication catapulted Sandor to a brief world-wide fame. Impressed as I might have been by his accomplishment, this was the part of his story that baffled me and prevented me from completing the film. I just could not connect with the so-called gravitas of Pooh/ Pu.

I once again turned to Godard, this time the 12-part television mini-series France/tour/detour/deux/enfants that he co-directed with Anne-Marie Miéville in 1977 and ‘78. Together, they produced an austere, ontological series of interview-style conversations with two children, a girl and a boy who appear to be about 10 years old. Watching these tapes reminds us that children are thinking, contemplative, confused, wise human beings who should be listened to from a very early age. After revisiting Godard and Miéville’s collaboration, with its low production values and bare-bones set, I was able to find a strategy for working with a children’s story that was at the center of my own film’s character but did not yet hold meaning for me.

Over a period of a year, I shot several cineme-verité style scenes with four children, including my own 10- and 8-year-old daughters and two of their friends. Together, they grappled with the challenge of putting on Winnie the Pooh as a play. In the process, each child searched for and excavated their own responses to Pooh — revelations that I, as an adult, had never been able to find on my own. In my The Last Happy Day, the inclusion of their considerations of, say, the meaning of death through the words of Eeyore the Donkey allowed me to locate the implicit paradoxes of my cousin’s own life, be it thwarted or nourished by the contradictions of his troubled times.

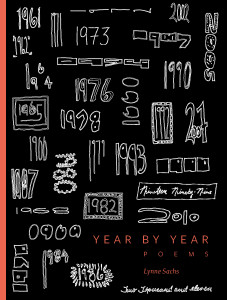

While making my 2017 feature-length essay film Tip of My Tongue, I tried to create a collective distillation of our times from the point of view of a group of friends and strangers from all corners of the globe. In the process, I gathered together eleven men and women born in the 1960s. One of my particular production challenges had to do with directing compelling scenes where people were delivering monologues, either to the camera or to another person. I wanted to activate the experience of listening as much as speaking. This time, Godard’s opening minutes from his 1965 Pierrot le Fou came to my rescue. In this simple yet extraordinarily memorable scene, actor Jean-Paul Belmondo plays a dapper father in the bathtub reading an art history tome on the paintings of Velasquez at the age of 50 to his young daughter. Clearly relevant to my film in terms of the artist’s age, the scene itself is poignant, profound and hilarious. After “studying” Godard’s own bathroom scene, I asked one of my film’s participants to draw some water, take off her shirt, get into bathtub, and tell her riveting story of athletic accomplishment and illness. The scene ultimately became the most talked-about and written-about scene from Tip of My Tongue. My gratitude to Jean-Luc abounds.

I recently completed Film About a Father Who (2020), which has its world premiere as the opening night movie at the Slamdance Film Festival this month and its New York City premiere in the Museum of Modern Art’s Documentary Fortnight in February. Over a period of 35 years between 1984 and 2019, I shot 8 and 16mm film, videotape, and digital images of my father. With a nod to the Cubist renderings of a face, my exploration of my father offers simultaneous, sometimes contradictory views of a man I should know pretty much everything about, but instead always find myself wondering. In the process of making this film, I allowed myself, my family, and my audience inside to see beyond the surface of the skin, his/my/our projected reality. As much as I might rack my brain to claim a debt to Godard in this, my most challenging movie so far, I must admit that I never actually found “Godardian” solutions to my decades-long list of obstacles to making Film About a Father Who. The only way I could finish this film was to take the obvious “risk” of going deep, deep inside.

https://projectr.tv/blog/single-take-lynne-sachs-on-jean-luc-godard