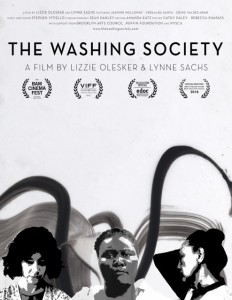

The Washing Society

a film by Lizzie Olesker and Lynne Sachs

44 min. 2018

When you drop off a bag of dirty laundry, who’s doing the washing and folding? THE WASHING SOCIETY brings us into New York City laundromats and the experiences of the people who work there. Collaborating together for the first time, filmmaker Lynne Sachs and playwright Lizzie Olesker observe the disappearing public space of the neighborhood laundromat and the continual, intimate labor that happens there. With a title inspired by the 1881 organization of African-American laundresses, THE WASHING SOCIETY investigates the intersection of history, underpaid work, immigration, and the sheer math of doing laundry. Drawing on each other’s artistic practices, Sachs and Olesker present a stark yet poetic vision of those whose working lives often go unrecognized, turning a lens onto their hidden stories, which are often overlooked. Dirt, skin, lint, stains, money, and time are thematically interwoven into the very fabric of THE WASHING SOCIETY through interviews and observational moments. With original music by sound artist Stephen Vitiello, the film explores the slippery relationship between the real and the re-enacted with layers of dramatic dialogue and gestural choreography. The juxtaposition of narrative and documentary elements in THE WASHING SOCIETY creates a dream-like, yet hyper-real portrayal of a day in the life of a laundry worker, both past and present.

Our collaborators include:

Laundry workers: Wing Ho, Lula Holloway, Margarita Lopez

Actors: Ching Valdes-Aran, Jasmine Holloway, Veraalba Santa

Cinematographer: Sean Hanley

Editor: Amanda Katz

Sound artist: Stephen Vitiello

Live Performance Producer: Emily Rubin, Loads of Prose

Criterion Channel streaming premiere with 7 other films, Oct. 2021.

Premiere

‘Punto de Vista’ International Documentary Film Festival, Pamplona, Spain

New York Premiere

BAMcinemaFest, Brooklyn Academy of Music; Indie Memphis Audience Award “Departures” (Avant-Garde) Category

Awards: Black Maria Film Festival Juror’s Stellar Award;

Festivals and Other Screenings: Sebastopol Documentary Film Festival; Athens Film and Video Festival; El Festival Internacional de Cine Documental “Encuentros del Otro Cine”, Ecuador; European Media Arts Festival, Osnabrück, Germany; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Anthology Film Archives, New York; Vancouver International Film Festival; Maine International Film Festival; Pacific Film Archive/ Berkeley Art Museum; Other Cinema, San Francisco; Queens World Film Festival; National Civil Rights Museum; Chicago Undergound Film Festival; Downtown Community Television; Scribe Video Center, Philadelphia; Cinema Parallels, Bosnia Herzogovina, 2021; Kinesthesia Festival, Birmingham, United Kingdom, 2021; Metrograph Theater, NYC, 2021.

University & College Screenings: Symposium on Black Feminist History, Carter Woodson Institute for African-American Studies, University of Virginia; University of Pennsylvania; Smith College; Mount Holyoke College; University of North Carolina; Dennison College; Amherst College; University of Buffalo; Tisch School of the Arts, New York University; Princeton University, Lewis Center for the Arts; Fashion Institute of Technology; University of California, Berkeley; University of Mississippi Center for the Study of Southern Culture; Yale University, African American Studies Dep’t.

Lynne’s co-director:

Lizzie Olesker is a writer, performer, and director in New York City where she creates theatrical works inspired by social and personal history. Her plays include Dreaming Through History; Verdure; A Kind (of) Mother; and Embroidered Past, seen at the Public Theater, Cherry Lane, Clubbed Thumb, Dixon Place, Here, and New Georges. Her solo performances include housework (St. Mark’s Church) and Infinite Miniature (Invisible Dog and Ohio Theater). Collaborations with other artists include the Talking Band (performing at La Mama and on international tour), Lenora Champagne (Tiny Lights) and upcoming with Louise Smith (Dorothy Lane). She’s received support from the New York Foundation for the Arts, Brooklyn Arts Council and the Dramatists Guild. She teaches playwriting at the New School and New York University where she’s active in the local UAW union for adjunct faculty.

Selected Press:

“Faced with the challenge of making a documentary for which the voices of undocumented immigrants were crucial, filmmakers Lynne Sachs and Lizzie Olesker had to push the boundaries of convention.” — “Bringing the Invisible to Light: Interview with Lynne Sachs and Lizzie Olesker” Cynthia Ramsay, Jewish Independent, Vancouver, BC, Canada, http://www.jewishindependent.ca/bringing-the-invisible-to-light/ )

“This is a slice of life, a celebration of humanity from the historic Atlanta washerwomen to the New York City workers of today in swirling brilliant color — color that comes from the flesh, hair and eyes of the workers, and the mountains of laundry they deal with every day, underwear, socks, sheets, shirts. One has to see it to believe it.” (J.P. Devine, Kennebec Journal, https://www.centralmaine.com/2018/07/16/j-p-devine-miff-movie-review-washing-society-charlie-chaplin-lived-here/ )

“An exercise in high-concept cinema to which Olesker and Sachs devote three quarters of an hour of film stock and many more quarters in tips, revealing the stains (of racism and classicism) on an American Dream that seems to want to scrub away every last trace of its own identity.” (Revolution in the Air & Theories of Weightlessness, Otro Cines Europa by Victor Esquirol, Punto de Vista International Film Festival, Pamplona, Spain, www.otroscineseuropa.com/aires-revolucion-teorias-la-ingravidez )

“Lizzie Olesker and Lynne Sachs’ film is a creative, often lyrical study of laundromat service workers in New York City – women who do a hard job for far too little money. Using a mixture of actors and real industry workers, the directors create a portrait of economic oppression and human resilience that provokes dismay and empathy in equal measure – and yet the hard dose of reality is leavened with poetic visual touches and a warm, humanist tone. What we hear – sometimes without subtitles – rings with authenticity, and it’s the details as much as the general situation of these workers that are alarming. One woman calculates that she washes around 1,000 articles of clothes a day; a “part-time” worker says she’s worked in laundromats for 45 years. How many socks is that? In voiceover, we hear that one of the goals the directors have is “calling attention to something that isn’t paid attention to – hidden labour.” On that score, their film is a success, but there is much else of value here besides journalistic advocacy; with their playful stylistic touches and creative approach to storytelling, Olesker and Sachs have turned politics into art – and vice versa.” Alan Franey, Vancouver International Film Festival, 2018.

THE WASHING SOCIETY has received support from Workers Unite Film Festival, New York State Council on the Arts, Brooklyn Arts Council, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Women and Media Coalition, Puffin Foundation and Fandor FIX Filmmakers.

For inquiries about rentals or purchases please contact Canyon Cinema or the Film-makers’ Cooperative. And for international bookings, please contact Kino Rebelde.

Post-Screening Conversation for

WASHING SOCIETY + CLOTHESLINES +A MONTH OF SINGLE

Metrograph, NYC

December 2021

Co-Directors Lynne Sachs and Lizzie Olesker with special guest feminist scholar Silvia Federici in a post-screening conversation. Hosted by Emily Apter.