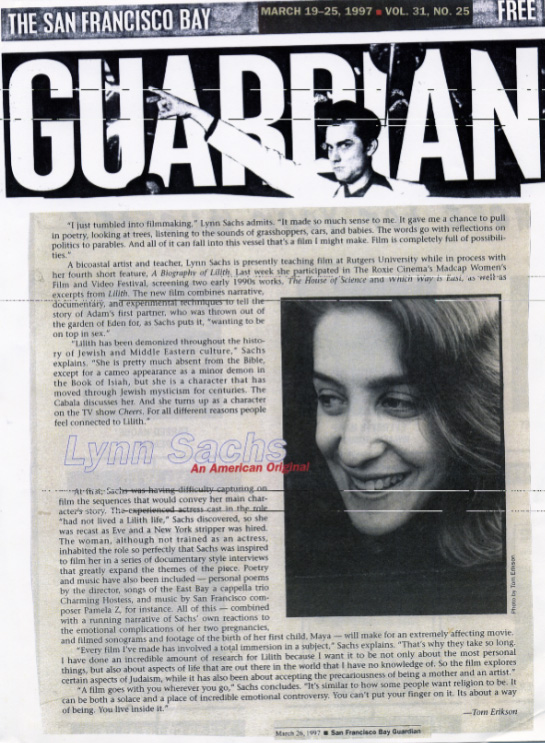

“Mary Moylan: 9 years underground” by Lynne Sachs

a multi-media biography using video, audio, postcards and artifacts

Premiere: Maryland Film Festival, Charles Theatre; Maryland Art Place Artist Residency

Mary Moylan, a 32-year-old registered nurse and midwife from Baltimore, was one of two women in the infamous 1968 anti-war group the Catonsville Nine. A feminist and a passionate critic of the Vietnam War, Moylan was sentenced to several years in prison for burning draft files with homemade napalm. From 1970-79, she lived underground, in disguise, traveling from city to city across America. During this time, Moylan –the felon on the lamb– created a fabulous wigged persona who wrote hilarious, yet strident letters to the world at large from her place “underground.” Mary Moylan: Nine Years Underground is a visual meditation not only on Moylan’s life as a woman in America in the 1970’s but also on the role of civil disobedience in American culture and politics.

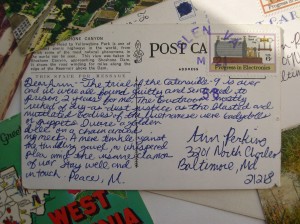

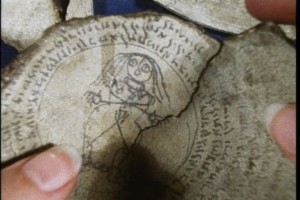

Entire piece measures 24’’ long x 24” wide x 24”high with simple electrical connections to TV/DVD ; all electronic appliances are hidden within purse and small suitcase. Gallery visitors listen to actress reading Moylan’s letters through headphones in purse. Small television images of a woman’s hands in handcuffs are under glass casing. Video and slide documentation give some idea of project, though set will no doubt change with the particulars of a space.

Below are excerpts from articles and interviews on Mary Moylan. Some of these texts are also under glass casing in the installation

Nine Catholic clergymen and laymen who oppose the war in Vietnam doused the Selective Service records of 600 draft-age men with napalm and set them afire yesterday in a cement lot behind the Catonsville draft board. …among the demonstrators was Mary Moylan, a 32-year-old registered nurse and midwife from Baltimore. The Baltimore Sun

May 18, 1968

A chipper Mary Moylan, the missing Catonsville Nine defendant who turned herself in to federal authorities after nine years in hiding, took the phone at the Women’s Detention Center today and gently refused to be interviewed.

“Where have you been these last nine years?” she was asked.

“Here and there,” Moylan answered, and laughed heartily.

“What have you been doing?”

“Oh, this and that.” The Baltimore Sun, June 20, 1979

Mary was so successful in her Orphic descent underground she lost contact with old comrades, friends and family. Some of the people who loved her most never saw her again. “She talked to me about things I would not have talked about,” remembers her sister Ella. “She didn’t go to our mother’s funeral in 1970 because she believed the FBI would be there. I think they were.” Mary Moylan died sometime in late April in Asbury Park, N.J. She was 59, alone and blind” The Baltimore Sun May, 1995

Below are authentic handwritten year-book style writings about Mary found on side panels of piece. These are thoughts by those who knew her before her life underground:

“I remember the bell she wore during the trial in Baltimore, a constant and wonderfully irritating tinkling throughout the proceedings.”

Bill O.

“After the action in Catonsville, we piled into the police van. I stared at Mary’s bright red hair and then noticed she was sliding her hands, ever so delicately, out of the cuffs.”

John H.

“She lay on the beach, a stack of trashy romance novels on her right side, Roszak’s The Making of a Counter Culture on the other.”

Willa B.

“She and the other members of Women Against Daddy Warbucks hurled 1000’s of draft files from an office building in Times Square.”

Bill O.

“She wouldn’t stay with families, the whole time she was underground. ‘Hon, it’s too damn dangerous,’ she told me. ‘If the FBI storms in looking for me, there’ll be gunfire. I can’t take that kind of risk with kids around.’”

Willa B.

“I met her on the boardwalk at Rehobeth. She was wearing a wig and stood a little hunched over.”

Brendan W.

“I think she died alone, somewhere in New Jersey, almost blind.”

Brendan W.