“Insurgent Articulations”

Curated by Ekin Pinar

Canyon Cinema Discovered Programs

September 27, 2022

https://canyoncinema.com/2022/05/03/announcing-the-canyon-cinema-discovered-programs/

“Insurgent Articulations”

Essay by Ekin Pinar

How to protest

1. Create a clear message

2. Make noise

3. Occupy a significant space

4. Engender fear through the sudden movement of a large mass of people, for example a march

How to celebrate carnival

1. Create a costume with a clear identity or message (…)

2. Make noise

3. Occupy a space significant to the community

4. Create a spectacle through the movement of a large mass of people, for example a parade. 5. Protest joyfully.

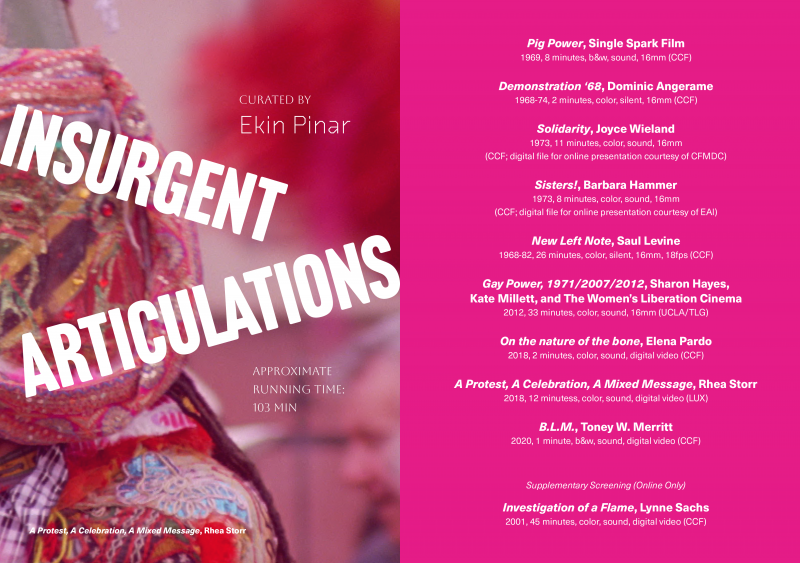

—Rhea Storr, A Protest, A Celebration, A Mixed Message, 2018

The opening voice-over of A Protest, A Celebration, A Mixed Message (Rhea Storr, 2018) outlines the dissenting, performative, affective, and public nature of protest events. While Rhea Storr poses a clear message as the prerequisite of protesting, the form and organization of the social event articulates the un-straightforward substance of protest. The film begins with this claim and challenges it through its course in a manner that mirrors protest events’ process of expression. Insurgent Articulations examines this parallel between protest as a cinematic subject matter and protest as determining the form and organization of film.

Focusing on the aesthetics of socio-political protest, the program showcases experimental films that reconstruct demonstrations, rallies, marches, and sit-ins in formally reflexive ways. In doing so, Insurgent Articulations explores cinematic reconstruction, reenactment, and the fictional fabrication of protest. These methods emphasize the productive tensions between on-site recording, retrospective consideration, and creative invention of political events. At the same time, these cinematic articulations of insurgent acts resist injustice, exclusion, and repression in ways that resonate with the challenges of protesters’ congregating bodies as they claim the right to express themselves in public space.

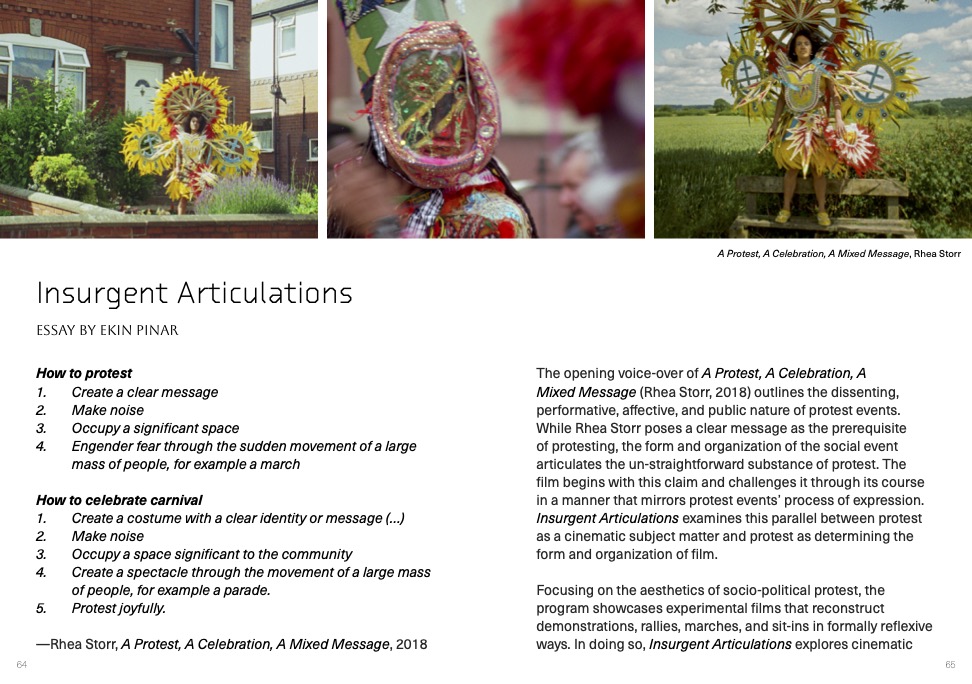

One of the many “turns” that have defined moving image culture in the last 25 years or so is documentary. Defined by a sustained and intense attention to the actual and fabricated Sisters!, Barbara Hammer archival, historical, and/or ethnographic documents, traces, and fragments of real and fictional events, beings, and objects, this tendency questions the authoritative, factual tone of conventional forms of documentary. Common strategies include re-enactments and re-stagings, essayistic modes, blurring of the factual and fictional, use of non-indexical media (especially animation), as well as aesthetic manipulation of the indexical documentation of the matters of the “real” world. As Hal Foster has noted, this documentary turn shifts documentary practice from deconstruction to reconstruction, engaging with the format as a critical and interpretative mode instead of a descriptive one. 1 Rather than claiming a direct mediation of the outside world, then, this mode approximates affective, corporeal, and situated/partial truths.

The documentary turn is unmistakably a reaction to the rise of digital media and the attendant proclamations of the “death of the indexical.” Yet, streaks of these self-reflexive documentary modes have existed in experimental film practices from the 1960s onwards. A strong interest in the social, political, and cultural aspects of our lifeworlds has been a significant part and parcel of experimental filmmaking practices. Yet, standard histories of experimental cinema outline a canon defined by subjective formal experimentations of the 60s that shifted in the 70s to a structuralist mode concerned with cinematic form. Because of this past focus on formal experimentation, the sociohistorical, cultural, and representational politics, ethics, and concerns of much experimental work remained unnoticed until more recently.

Insurgent Articulations puts contemporary work in dialogue with the histories of experimental documentary—highlighting correspondences of subject matter, representational strategies, and organizational modes. This retrospective assessment challenges the periodizing accounts of experimental film history by underlining the experimental film production’s persistent interest in the social and political events of the world. At the same time, the program invites viewers to reconsider the false binary between aesthetic experimentation and a political commitment to the actual world.

Experimental films that take protest as their subject provide an especially fecund ground for the examination of the tightly woven interchange between formal experimentation and political subject matter. In her discussion of protest, Hito Steyerl emphasizes two interrelated layers of expression: The first layer involves what is being protested and the discovery of an appropriate and effective verbal and visual language for the substance of protest. The second concerns how the assembly of people organizes itself for the purpose of protest and communicates this internal organization to the public. 2 The films in this program articulate both levels of articulation. They visualize assemblies of resistance, while also reflecting formal, structural, and organizational concerns that parallel the aesthetics of protest. Reflexively considering issues of witnessing, performance, assemblage, and the formation of counterpublics both in terms of aesthetic form and political content, the films highlight the fluid and complex relations between art and politics, and fact and fiction.

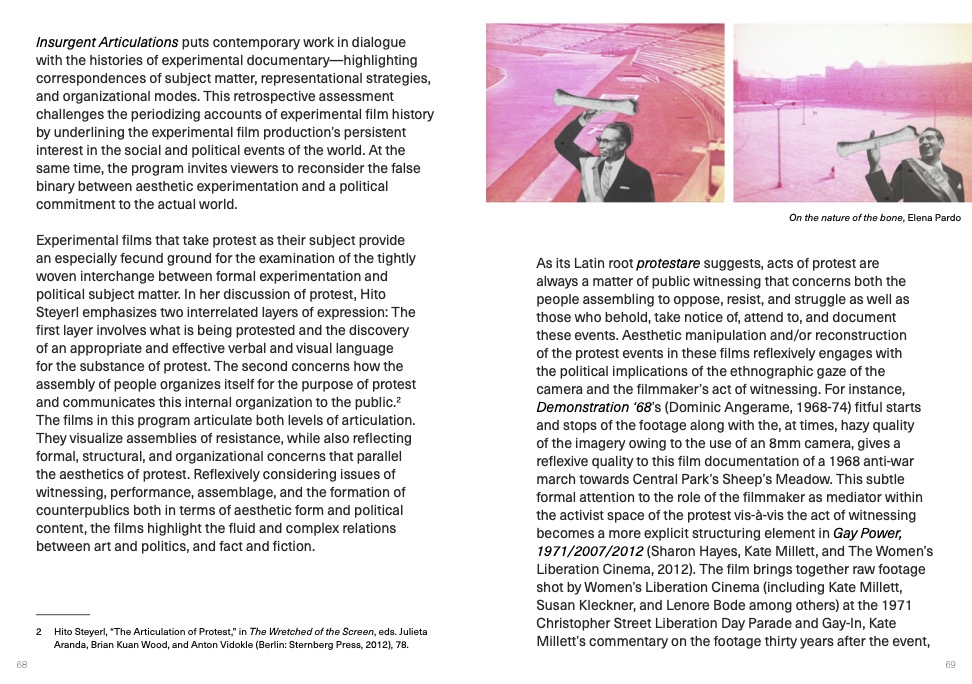

As its Latin root protestare suggests, acts of protest are always a matter of public witnessing that concerns both the people assembling to oppose, resist, and struggle as well as those who behold, take notice of, attend to, and document these events. Aesthetic manipulation and/or reconstruction of the protest events in these films reflexively engages with the political implications of the ethnographic gaze of the camera and the filmmaker’s act of witnessing. For instance, Demonstration ‘68’s (Dominic Angerame, 1968-74) fitful starts and stops of the footage along with the, at times, hazy quality of the imagery owing to the use of an 8mm camera, gives a reflexive quality to this film documentation of a 1968 anti-war march towards Central Park’s Sheep’s Meadow. This subtle formal attention to the role of the filmmaker as mediator within the activist space of the protest vis-à-vis the act of witnessing becomes a more explicit structuring element in Gay Power, 1971/2007/2012 (Sharon Hayes, Kate Millett, and The Women’s Liberation Cinema, 2012). The film brings together raw footage shot by Women’s Liberation Cinema (including Kate Millett, Susan Kleckner, and Lenore Bode among others) at the 1971 Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade and Gay-In, Kate Millett’s commentary on the footage thirty years after the event, Solidarity, Joyce Wieland and Sharon Hayes’s narration of her own reactions to this historical footage. The resulting complex, multilayered text puts various modes of witnessing in conversation with one another: through the lens of the camera (Women’s Liberation Cinema), as a retrospective act (Millett), and as a documentary spectator and reassembler (Hayes).

The presentational aspects of protest events directed at onlookers clearly produce a performative dimension. Replay, retrospection, and reenactment involved in the multilayered structuring of Gay Power simultaneously indexes these performative aspects of protest events. In its analogy between a carnival and a protest parade, A Protest, A Celebration, A Mixed Message also highlights this performative dimension at the Leeds West Indian carnival in Yorkshire, UK. The film emphasizes the racial dimension of the performance in its arrangement of white people as spectators and Black people as performers who are, at the same time, consciously defiant of the white gaze. Yet, a sudden shift to the calm countryside where Storr walks alone in her parade costume calls attention to a different spatial context that lacks an audience for a protesting/ performing rural, mixed-race body. In a similar vein, the editing tactics of Sisters! (Barbara Hammer, 1973) brings together footage from First Women’s March (Height Ashbury, San Francisco, 1973), a concert at the West Coast Lesbian Feminist Conference (UCLA, 1973), and several women performing putatively male labor in conscious address of the camera. In Investigation of a Flame (Lynne Sachs, 2001), the editing similarly alternates between different performative events: the archival footage of the Catonsville Nine burning draft records, military parades featuring children dressed up as soldiers, and Catonsville home movies in which addressing and playacting for the camera reign.

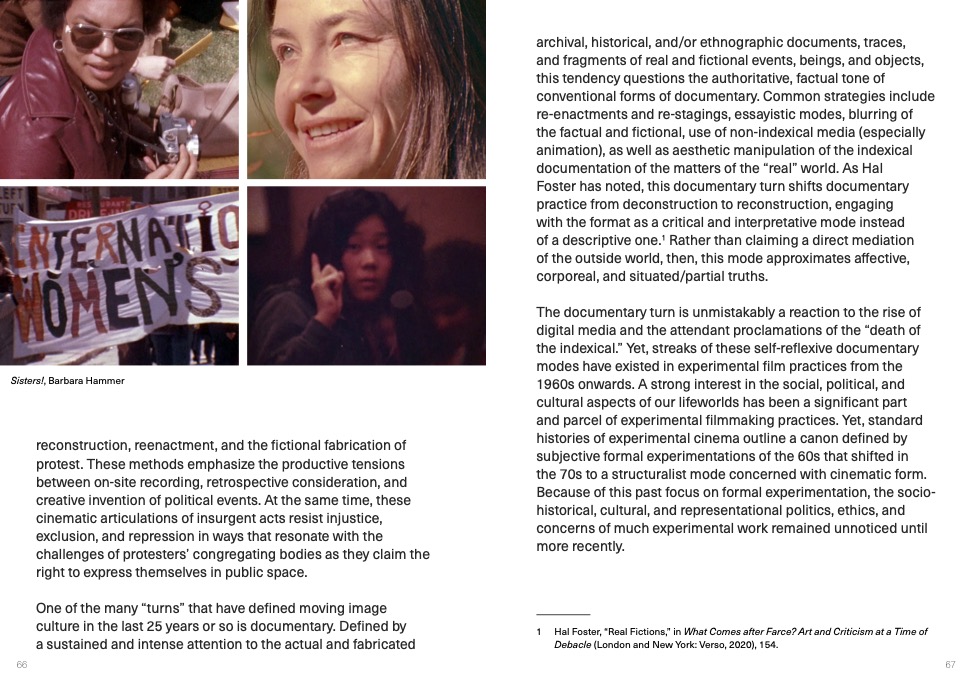

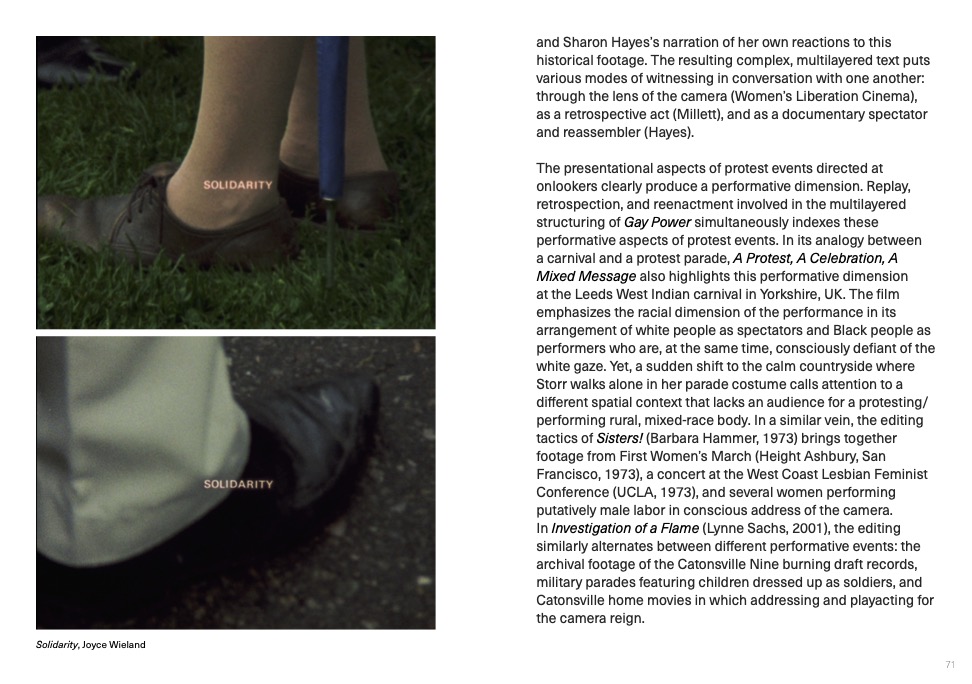

A protest event becomes a performative one to the extent that it is a bodily assembly of people enacting solidarity and resistance for others to take notice. Underscoring the distinction between the freedom of assembly and freedom of expression, Judith Butler describes how the corporeal, performative gathering of a group of people forms an extra layer of meaning beyond the verbal expression of the protest. 3 This distinction between verbal expression and bodily performance is exactly what configures the image-sound relations in Solidarity (Joyce Wieland, 1973). Focusing on a strike at the Dare Cookie Factory in Kitchener, Ontario, the film edits together the feet, shoes, and legs of marching and picketing workers with the organizer’s speech on the soundtrack. Despite the unified message on the level of verbal expression, the defamiliarization achieved by the unusual attention to the feet emphasizes the plurality in solidarity. Such a parallel between cinematic editing and the structuring of protest is the organizational principle of New Left Note (Saul Levine, 1968-82), which not only assembles bodies but also assembles events with different temporal registers. New Left Note articulates this intertextuality through its fast-cut editing of scenes from various protests by the Black Panthers and feminist and anti-war movements among others. On the nature of the bone (Elena Pardo, 2018) likewise establishes a link between the massacre of students in 1968 at the Tlatelolco Plaza and the current political atmosphere in Mexico. Through its juxtaposition of past and contemporary found footage, photographs, and drawings, the film offers an animated reenactment of history.

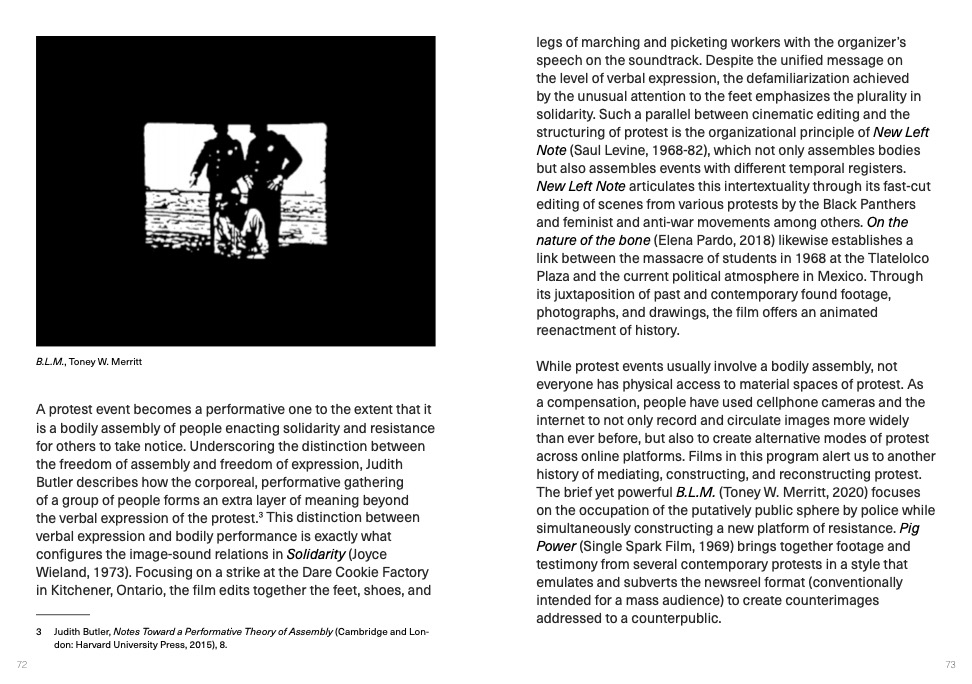

While protest events usually involve a bodily assembly, not everyone has physical access to material spaces of protest. As a compensation, people have used cellphone cameras and the internet to not only record and circulate images more widely than ever before, but also to create alternative modes of protest across online platforms. Films in this program alert us to another history of mediating, constructing, and reconstructing protest. The brief yet powerful B.L.M. (Toney W. Merritt, 2020) focuses on the occupation of the putatively public sphere by police while simultaneously constructing a new platform of resistance. Pig Power (Single Spark Film, 1969) brings together footage and testimony from several contemporary protests in a style that emulates and subverts the newsreel format (conventionally intended for a mass audience) to create counterimages addressed to a counterpublic.

The films in Insurgent Articulations establish spatial and temporal connections across multiple sites of protest. Doing so, these films also hint at the community-forming capabilities of the circulation and exhibition practices of experimental cinema in the form of co-ops and cine clubs (for instance, Canyon Cinema and The Film-Makers’ Cooperative in the US, Nihon University New Film Study Club in Japan, and Genç Sinema in Turkey, to name only a few). In their thematic, organizational, and formal interest in the significant social and political events that are shaped by and, in turn, constitute our shared lifeworlds, the works in this program go against the theoretical and historiographic traditions that have for so long associated avant-garde film practices with individualistic forms of expression. They suggest new ways of engaging with histories of experimental cinema that highlight resonances, continuities, and entanglements that challenge established periodizations and geographic boundaries. Across this rich tapestry of experimental representations of protest, we find another mode of resistance—one that defies easy historical categorization.

Edited by Tess Takahashi

_____________

1 Hal Foster, “Real Fictions,” in What Comes after Farce? Art and Criticism at a Time of Debacle (London and New York: Verso, 2020), 154.

2 Hito Steyerl, “The Articulation of Protest,” in The Wretched of the Screen, eds. Julieta Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood, and Anton Vidokle (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), 78.

3 Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2015), 8.