Monira Foundation In Collaboration with Film Diary NYC presents:

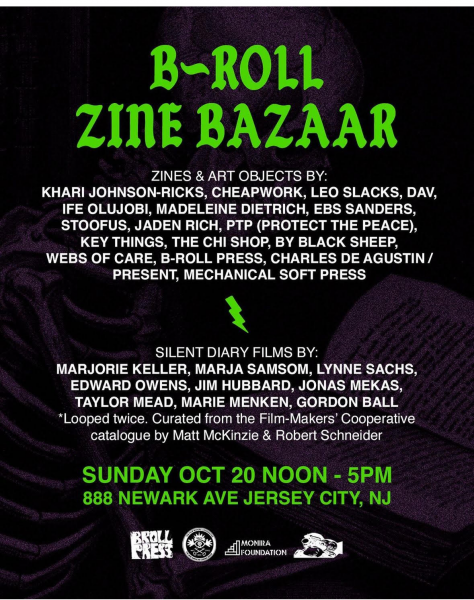

B-Roll Zine Bazaar

October 20, 2024 12-6pm

1st Floor Cinema, 888 Newark Ave

B-Roll Zine Bazaar will feature a curated selection of artists and book-makers offering zines, prints, and ephemera. The bazaar will take place in the Mana Legacy cinema room on the first floor of Mana Contemporary, with a 6-hour long screening of silent diary films happening simultaneously. Vendors and filmmakers TBA in early October.

About B-Roll Press & Zine Bazaar

B-Roll Press is a micropress founded by Saint Piñero and Sage Ó Tuama in 2020, publishing zines by photographers and filmmakers who focus on the personal and poetic from the fringes of society. B-Roll is one facet of Saint and Sage’s shared curatorial practice which also encompasses Film Diary NYC.

The first edition of B-Roll Zine Bazaar will be an experiment that merges our film curation with our interest in self-publishing.

Places, Politics, Performances: Diaries from the Film-Makers’ Cooperative

Curated by Matt McKinzie and Robert Schneider for B-Roll Press’ Zine Bazaar, organized by Saint Piñero and Sage Ó Tuama

Join us at Mana Contemporary on SUNDAY, OCTOBER 20th, at 12pm, for a program of silent diary films from the FMC’s collection, curated by Matt McKinzie and Robert Schneider for B-Roll Zine Bazaar, organized by Saint Piñero and Sage Ó Tuama of Film Diary NYC!

PROGRAM:

I. Diaries of Performance:

She/Va, Marjorie Keller, Super 8mm-to-digital, 3 minutes, 1973

How a Sculpture Eats a Painting, Marja Samsom, Super 8mm-to-digital, 5 minutes, 1975

Picnic, Marja Samsom, Super 8mm-to-digital, 3 minutes, 1975

Hoover, Marja Samsom, Super 8mm-to-digital, 3 minutes, 1977

II. The Personal is Political:

The Jitters, Lynne Sachs, 16mm-to-digital, 3 minutes, 2023

Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts, Edward Owens, 16mm-to-digital, 6 minutes, 1966

Elegy in the Streets, Jim Hubbard, 16mm-to-digital, 30 minutes, 1989

III. Out of the City and Into the Countryside:

Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Jonas Mekas, 16mm-to-digital, 16 minutes, 2003

Home Movies / NYC to San Diego, Taylor Mead, 16mm-to-digital, 13 minutes, 1968

Sidewalks, Marie Menken, 16mm-to-digital, 6 minutes, 1966

Lights, Marie Menken, 16mm-to-digital, 6 minutes, 1966

Excursion, Marie Menken, 16mm-to-digital, 5 minutes, 1968

Notebook, Marie Menken, 16mm-to-digital, 11 minutes, 1962

Farm Diary, Gordon Ball, Super 8mm-to-digital, 64 minutes, 1964

Total Run Time: 174 minutes.

*To be screened twice during the zine bazaar.

Notes by Matt McKinzie and Robert Schneider:

The Film-Makers’ Cooperative is honored to present a three-hour program of silent diary films for B-Roll Press’ Zine Bazaar at Mana Contemporary, organized by Saint Piñero and Sage Ó Tuama of Film Diary NYC. One of the oldest and largest distributors of avant-garde films, video, and media art in the world, the Film-Makers’ Cooperative (FMC) was founded in New York City in 1961 by a group of 22 experimental moving image artists aiming to cultivate an alternative space for filmmakers working outside of the mainstream. With works like Walden (1969) and Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972), FMC co-founder Jonas Mekas helped pioneer the “diary film,” defined by Film Diary NYC as “experimental, autobiographical films that capture the personal history and daily experiences of the filmmaker.” In presenting this collection of diaristic work, we hope to echo Mekas’ and Film Diary’s mission of championing art that illuminates its makers’ interiorities, observations, day-to-day experiences, and the spaces and communities in which they live and work.

Split into three sections, this lineup highlights work from the FMC’s holdings that spans from its inception in the early 1960s to as recent as 2023. The first section examines the role of performance and role-playing in personal filmmaking. In former FMC director Marjorie Keller’s Super-8mm found footage/home movie She/Va, a young dancer is “re-choreographed through film editing.” Subsequently, the Super-8mm self-portraits How a Sculpture Eats a Painting, Picnic, and Hoover find performance artist Marja Samson acting out micro-narratives in disparate everyday settings, in turn presenting a “conceptual museum fantasy,” a “Georges Méliès-influenced scene interrupted by a tiger,” and a “glamorous resistance on housekeeping.” That Samson’s and Keller’s films engage with gender roles and notions of femininity and performance feels pertinent considering they were made during the height of the second-wave feminist movement in the 1970s.

Lynne Sachs’ recent 16mm short The Jitters is classified by the artist as a “performance,” thereby bridging the first section with the second, which consists of diaristic work that exemplifies the adage “the personal is political.” In The Jitters, Sachs and her partner Mark Street “jitter” around their bedroom in the nude, as captured by Sachs’ Bolex. Sachs writes: “I wanted to create a film with my Bolex 16mm camera that reflects who I am at this moment in my life. I bought my camera in 1987, used. It has lived with me for four decades, and it has witnessed pretty much every aspect of my existence.”

Equal parts playful and revelatory, The Jitters is as much a performance as it is a radical celebration of bodies, intimacy, aging, and longevity — the longevity not only of Sachs’ and Street’s partnership, but of Sachs’ four-decade relationship with her filmic apparatus and its role in documenting her life and the lives of her friends and family.

Friends and family are recurrent in the work of Edward Owens, a Black, gay filmmaker who was, for decades, written out of the history of the American avant-garde despite being a key member of the New American Cinema movement and a protégé of both Jonas Mekas and Gregory Markopoulos. His mother and friends appear frequently in his work, though perhaps most indelibly in his 1966 evocation Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts. Made at the height of the Civil Rights movement, Owens’ intermingling of dreamlike footage of Black and white relatives and peers feels groundbreaking, as does the tender intimacy with which he conveys them. Owens’ footage of his mother in particular, engaging in quotidian activities at home (resting, conversing, smoking a cigarette, having a glass of water), offers a rare antidote to the images of suffering and subjugation experienced by Black people that were rife in mainstream American filmmaking throughout the 1960s.

While Owens does not explicitly contextualize these private moments from his personal life within a broader historical or political moment, Elegy in the Streets sees Jim Hubbard directly correlate home footage of his partner Rober Jacoby (who passed away due to complications from AIDS) with 16mm footage of AIDS marches, protests, and vigils in the 1980s. Hubbard notes: “The film attempts to create a filmic rendering of the elegiac form, utilizing a procession of mourners, a catalog of flowers, a visit to the underworld and other poetic techniques… The film is nearly 30 minutes long and silent… that is a lot to ask of an audience, but it is silent for several crucial reasons. First, it is a literalization of the phrase ‘Silence = Death.’ Second, I live in New York City, a very loud place to live and, for me, silence is a great luxury. Third, I believe that film is a visual medium and sound is typically used to manipulate and limit the emotional response of the audience. I want each member of the audience to experience the film uniquely and personally. Silence forces the viewer to really look at what there is to see.”

In addition to “exploring the AIDS crisis from both a personal and a political perspective,” Elegy in the Streets functions as a city symphony film — composed of images of New York City, its residents, and its infrastructure during a significant historical period. This designation bridges the second section of the program with the third and final one, which presents a suite of diary films exploring lived environments.

In effect, this section charts a filmic journey out of the city and into the countryside, beginning with Jonas Mekas’ Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which amalgamates footage Mekas shot while first living in Williamsburg in 1950 with footage of the same neighborhood that Mekas shot in 1972. Critic Max Goldberg describes the film (which was not assembled and placed into distribution until 2003) as a “pocket-sized city symphony” in which “bygone Brooklyn is richly evoked in the everyday life of the street: the elevated train, Lithuanian storefronts and especially in the faces of children surprised to encounter this man with a movie camera.” Similar to Mekas’ Williamsburg, Brooklyn is Taylor Mead’s Home Movies / NYC to San Diego, which takes the viewer on, as Mead himself described it, “The Grand Tour” through a “millennium of culture” and was shot on the “cheapest, littlest hand-held camera I could buy.”

Four shorts by Marie Menken follow, wherein the trailblazing avant-garde filmmaker documents (to quote John Hawkins) “the magic patterns in the pavements of a city” (Sidewalks) and abstractly renders displays of Christmas lights on a wintry nighttime stroll (Lights), before embarking on a sped-up boat ride outside of New York (Excursion) and landing in a sylvan environment of trees and leaves far beyond the metropolis (Notebook). Gordon Ball’s hour-long personal documentary Farm Diary (which concludes the program) continues that sylvan journey, and features “ghostly strangers” (among them: Peter and Julius Orlovsky, Candy O’Brien, and Allen Ginsberg) on Ball’s mountaintop farm during, to quote Ginsberg, “the archetypal first year back to the land.”