May 2020

Sarasota Film Festival – Q&A with Lynne Sachs on Film About a Father Who

Lynne Sachs discusses her feature documentary “Film About a Father Who” with Harrison Bender of the Sarasota Film Festival.

May 2020

Sarasota Film Festival – Q&A with Lynne Sachs on Film About a Father Who

Lynne Sachs discusses her feature documentary “Film About a Father Who” with Harrison Bender of the Sarasota Film Festival.

Screening of Film About a Father Who and Q&A with Lynne Sachs

Available May 16, 8:00 AM – May 17, 4:00 AM, 2020] Watch now in our online Virtual Festival

https://watch.eventive.org/vailfilmfestival/play/5ea61530e5745b0029223a20

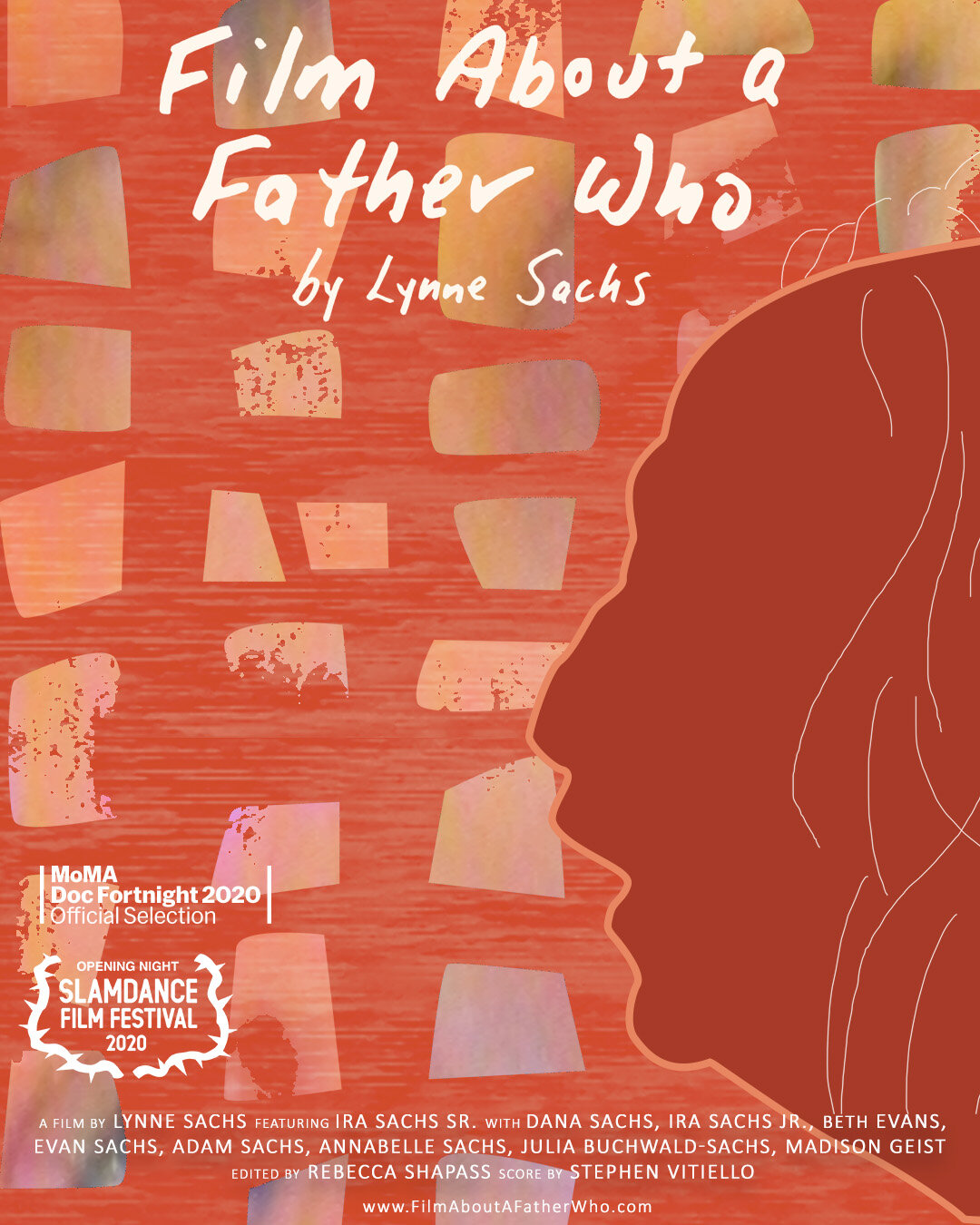

Film About a Father Who (USA, 74minutes)

Director: Lynne Sachs

From 1984 to 2019, filmmaker Lynne Sachs shot film, videotape and digital images with her father, Ira Sachs, a bohemian businessman from Park City. This film is her attempt to understand the web that connects a child to her parent and a sister to eight siblings, some of whom she has known all of her life, others she only recently discovered. With a nod to the Cubist renderings of a face, her film offers sometimes contradictory views of one seemingly unknowable man who is always there, public, in the center of the frame, yet somehow ensconced in secrets.

“This divine masterwork of vulnerability weaves past and present together with ease, daring the audience to choose love over hate, forgiveness over resentment. Sachs lovingly untangles the messy hair of her elusive father, just as she separates and tends to each strand of his life. A remarkable character study made by a filmmaker at the top of her game– an absolute must see in Park City.”

—Michael Gallagher, Programmer

https://watch.eventive.org/vailfilmfestival/play/5ea61530e5745b0029223a20

May 2020

Competition Selection 2020

International Competition

The world’s oldest short film competition is a forum for experiments, unusual content and formats, and the place for cinematic discoveries. Every year, filmmakers from all over the world present themselves here.

The International Competition selection includes artistic contributions from all genres, explores the freedom of the short form, surprises and enriches the audience. The industry audience research new films here and a premiere screened in this competition is often a springboard for selection by other festivals – not least for the Oscar (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences).

The competition presents a selection of the most interesting works of the year and invites filmmakers from all over the world to present their work in person. In the International Competition, only German festival premieres are shown, including numerous world premieres. There is also a focus on works from countries outside the strong production infrastructures, especially from Eastern and South Eastern Europe and the African states.

The films selected by an independent committee from well over 6,000 submissions compete for prize money of 25,500 €. Prizes are awarded by four juries: the International Jury, the Jury of the Ministry of Culture and Science of North Rhine-Westphalia, the Ecumenical Jury and the FIPRESCI Jury.

Jury of the International Competition 2020

Frank Beauvais, filmmaker, France

Lerato Bereng, curator, South Africa

Dmitry Frolov, curator, Russia

Michał Matuszewski, curator, Poland

Brittany Shaw, curator, USA

Among the international competition films were works by

Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Santiago Álvarez, Lindsay Anderson, Roy Andersson, Kenneth Anger, Andrea Arnold, Yael Bartana, Neil Beloufa, Jürgen Böttcher, Walerian Borowczyk, Stan Brakhage, Vera Chytilová, Jem Cohen, Terence Davies, Khavn De La Cruz, Valie Export, Milos Forman, Robert Frank, Karpo Godina, James Herbert, Takashi Ito, Joris Ivens, Ken Jacobs, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Isaac Julien, Miranda July, William Kentridge, Jan Lenica, George Lucas, Dusan Makavejev, Jonas Mekas, Mike Mills, Kornel Mundruczo, Robert Nelson, Yoko Ono, Adina Pintilie, Roman Polanski, Laure Prouvost, Alain Resnais, Pipilotti Rist, Martin Scorsese, Cate Shortland, John Smith, Michael Snow, Alexander Sokurov, Jan Svankmajer, Eva Stefani, István Szabó, Matsumoto Toshio, François Truffaut, Gus Van Sant, Agnès Varda, Bill Viola, Apitchatpong Weerasethakul, Jia Zhang-Ke, Zelimir Zilinik

Australia

Cuckoo Roller, Paddy Hay, 2019, 15’10”, International Competition

The Echo, Michael Gupta, 2020, 02’30”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Austria

Heavy Metal Detox, Josef Dabernig, 2019, 12’00”, International Competition

Pomp, Katrina Daschner, 2020, 07’43”, International Competition

Austria/Germany

The Institute, Alexander Glandien, 2020, 13’00”, German Competition

This Makes Me Want to Predict the Past, Cana Bilir-Meier, 2019, 16‘05‘‘, German Competition

Belgium

Le Poisson fidèle, Atelier Collectif, 2019, 07’40”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Belgium/Georgia

Da-Dzma, Jaro Minne, 2019, 15’36”, International Competition

Brazil

Baile, Cíntia Domit Bittar, 2019, 18’00”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

O Jardim Fantástico, Fábio Baldo/Tico Dias, 2020, 20’30”, International Competition

Canada

Le mangeur d’orgues, Diane Obomsawin, 2019, 01’19”, International Competition

Oursons, Nicolas Renaud, 2019, 09’10”, International Competition

Canada/Portugal

The Initiation Well, Chris Kennedy, 2020, 03’30”, International Competition

Chile

Extrañas Criaturas, Cristina Sitja/Cristobal Leon, 2019, 15’00”, International Competition/Children’s and Youth Film Competition

China

I Am the People_I, Li Xiaofei, 2019, 25’00”, International Competition

Phoenix, Su Zhong, 2020, 07’27”, International Competition

Colombia

PLATA O PLOMO, Nadia Granados, 2019, 04’19”, International Competition

Ramón, Natalia Bernal Castillo, 2020, 07’10”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Croatia

Porvenir, Renata Poljak, 2020, 12’15”, International Competition

Strujanja, Katerina Duda, 2019, 16’10”, International Competition

Cuba

Las Muertes de Arístides, Lázaro Lemus, 2019, 16’10”, International Competition

Czech Republic

Apparatus as a Goal of History, Zbyněk Baladrán, 2019, 13’52”, International Competition

Milenina píseň, Anna Remešová/Marie Lukacova, 2019, 09’01”, International Competition

Finland

Patentti Nr. 314805, Mika Taanila, 2020, 02’16”, International Competition

Talvinen järvi, Petteri Saario, 2019, 15’00”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Finland/Hungary

Crossing Paths, Éva Freund, 2019, 09’55”, International Competition

France

Cœur Fondant, Benoît Chieux, 2019, 11’20”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Esperança, Cécile Rousset/Jeanne Paturle/Benjamin Serero, 2019, 05’25”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Never look at the Sun, Baloji, 2019, 05’16”, International Competition

Mat et les gravitantes, Pauline Penichout, 2019, 26’00”, International Competition

Moutons, loup et tasse de thé…, Marion Lacourt, 2019, 12’10”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Sous la canopée, Bastien Dupriez, 2019, 06’38”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Têtard, Jean-Claude Rozec, 2019, 13’40”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Un lynx dans la ville, Nina Bisiarina, 2019, 06’48”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

France/Argentinia

Aquí y allá, Melisa Liebenthal, 2019, 21’41”, International Competition

France/China

Nan Fang Shao Nv (She Runs), Qiu Yang, 2019, 19’32”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

France/Germany

Sans plomb, Louise Groult, 2019, 08‘00‘‘, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

France/Morocco

Sukar, Ilias El Faris, 2019, 09’00”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

France/South Africa/Germany

Shepherds, Teboho Edkins, 2020, 27’00”, German Competition/International Competition

France/South Korea

Boriya, Min Sung Ah, 2019, 17’13”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Georgia/Germany

Scenes from Trial and Error, Tekla Aslanishvili, 2020, 32’00”, German Competition

Germany

Abgelaufen, Roman Schaible, 2019, 04’39”, MuVi Award

AQUA IMPROMPTU, Ebba Jahn, 2019, 13’12”, German Competition

attractions, Patrick Wallochny, 2019, 04’16”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Beasts Of No Nation, Krzysztof Honowski, 2019, 09’28”, German Competition

Becky’s Weightloss Palace, Bela Brillowska, 2020, 08’00”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Berzah, Deren Ercenk, 2020, 26’22”, NRW Competition

Causality and Meaning, Martin Brand, 2020, 09’17”, German Competition

Chico Crew I, Christine Gensheimer, 2020, 2’17”, MuVi Award

Das war unsere BRD, Ariane Andereggen/Ted Gaier, 2019, 10’01”, MuVi Award

Der natürliche Tod der Maus, Katharina Huber, 2020, 21’34”, German Competition

Die sehen ja nur, die wissen ja nichts, Silke Schönfeld, 2020, 26’58”, NRW Competition

Dunkelfeld, Marian Mayland/Patrick Lohse/Ole-Kristian Heyer, 2020, 17’35”,German Competition

Eurydike, Zaza Rusadze/Andreas Reihse, 2020, 03’45”, MuVi Award

Freeze Frame, Soetkin Verstege, 2019, 05’00”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Ganze Tage zusammen, Luise Donschen, 2019, 23’00”, German Competition

If there is love, you will take it, Daniel Hopp, 2020, 10’41”, German Competition

Im toten Park, Moritz Liewerscheidt, 2019, 08’00”, NRW Competition

Introspektion, Hamid Kargar, 2019, 04’14”, MuVi Award

Jona, Jonathan Schaller, 2019, 16’12”, NRW Competition

Kunst, Dietrich Brüggemann, 2019, 03’57”, MuVi Award

L’Artificio, Francesca Bertin, 2020, 23’00”, German Competition

Labor of Love, Sylvia Schedelbauer, 2020, 11’30”, German Competition

Mad Mieter, M + M (Weis/De Mattia), 2019, 06’09”, German Competition

Nackenwirbel, DIE GLITZIES/Nina Werner/Simon Quack/André Siegers/Bernd Schoch, 2020, 05’53”, MuVi Award

Passage, Ann Oren, 2020, 12’48”, German Competition

Phoenix, Florian Felix Koch, 2020, 13’32”, NRW Competition

Play Me That Silicon Waltz Again, Rainer Knepperges, 2019, 03’41”, NRW Competition

schichteln, Verena Wagner, 2019, 21’28”, German Competition

Shadowbanned, Jan Lankisch, 2020, 03’28”, MuVi Award

Semiotics of the City, Daniel Burkhardt, 2020, 04’00”, NRW Competition

SUGAR, Bjørn Melhus, 2019, 20’30”, German Competition

there may be uncertainty, Paul Reinholz, 2020, 28’58”, NRW Competition

Vicious, Lucie Friederike Mueller, 2019, 02’35”, MuVi Award

VIVE LA LIBERTÉ, Dieter Reifarth/Vollrad Kutscher, 2019, 05’32”, German Competition

Wer sagt denn das?, Timo Schierhorn/UWE, 2019, 03’00”, MuVi Award

Germany/India

them people, Nausheen Javed, 2020, 05’37”, NRW Competition

Germany/Jordan

The Ghosts We Left at Home, Faris Alrjoob, 2020, 21’00”, German Competition

Germany/Latvia

Klusā daba, Anna Ansone, 2020, 22’00”, NRW Competition

Germany/Turkey

Letters from Silivri, Adrian Figueroa, 2019, 15’50”, German Competition

Onun Haricinde, İyiyim, Eren Aksu, 2020, 14’00”, German Competition

Germany/Ukraine

Nolove, Sergii Kushnir, 2020, 03’27”, MuVi Award

Germany/USA

Sketch Artist, Loretta Fahrenholz, 2019, 03’44”, MuVi Award

Ghana

King of Sanwi, Akosua Adoma Owusu, 2020, 07’18”, International Competition *

Greece

BELLA, Thelyia Petraki, 2020, 24’30”, International Competition

Hungary/Armenia

What We Still Can Do, Nora Ananyan, 2019, 14’34”, International Competition

India

Bittersweet, Sohrab Hura, 2019, 13’48”, International Competition

Ireland

Christy, Brendan Canty, 2019, 14’17”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Receiver, Jenny Brady, 2019, 14’36”, International Competition

Japan

Chinbin Western, Kazoku no Hyosho (Chinbin Western, Representation of the family), Chikako Yamashiro, 2019, 32’00”, International Competition

yumemi banani utsutsu (Dreaming Away), Yuta Masuda, 2019, 09’38”, International Competition

Kyrgyzstan

Abzel, Aizhamal Akchalova, 2019, 11’47”, International Competition

Ayana, Aidana Topchubaeva, 2019, 20’44”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Latvia

MAN, Yulia Timoshkina, 2020, 11’45”, International Competition

Malaysia

Camera Trap, Chris Chan Fui Chong, 2019, 09’40”, International Competition

Mexico

( ( ( ( ( /*\ ) ) ) ) ) (ecos del volcán), Charles Fairbanks/Saul Kak, 2019, 18’15”, International Competition

Dresden Codex, Colectivo los ingrávidos, 2019, 04’59”, International Competition

Nepal

Junu Ko Jutta, Kedar Shrestha, 2019, 13’02”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Netherlands

Elf, Luca Meisters, 2019, 12’52”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

En route, Marit Weerheijm, 2019, 10’09”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

L’eau Faux, Serge Onnen/Sverre Fredriksen, 2020, 15’30”, International Competition

Zachte Krachten, Julia Kaiser, 2019, 20’56”, International Competition

Norway

Cuojnasat, Ann Holmgren, 2019, 02’34”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Philippines

Escape Velocity, Jon Lazam, 2019, 02’00”’, International Competition

We still have to close our eyes, John Torres, 2019, 13’00”, International Competition

Poland

Śnię o Rosji, Evgeniia Klemba, 2020, 08’50”, International Competition

Portugal

Six Portraits of Pain, Teresa Villaverde, 2019, 25’02”, International Competition

Singapore

The Smell of Coffee, Nishok Nishok , 2019, 11’38”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

South Korea

Front Door, Ye-jin Lee, 2019, 03’12”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Spain

Grietas, Alberto Gross, 2019, 12’23”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Profecía, Julieta Juncadella, 2020, 13’11”, International Competition

Sweden

En film, Mårten Nilsson, 2019, 04’14”, International Competition

Jamila, Sophie Vukovic, 2019, 13’02”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Switzerland

Alma Nel Branco, Agnese Làposi, 2019, 24’50”, International Competition

Der kleine Vogel und die Bienen, Lena von Döhren, 2020, 04’30”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Gira Ancora, Elena Petitpierre, 2019, 22’09”, International Competition

Warum Schnecken keine Beine haben, Aline Höchli, 2019, 10’44”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Switzerland/UK

Getting Started, William Crook, 2019, 02’01”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Taiwan

Wan Ru Yan Huo (Like Fireworks), Ting-wei Chang,, 2019, 15’00”, Kinder- und Jugendfilmwettbewerb

Thailand

I’m Not Your F***ing Stereotype, Hesome Chemamah, 2019, 28’59”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Turkey

Ahtapot, Engin Erden, 2019, 12’26”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

MAMAVILLE, Irmak Karasu, 2019, 20’46”, International Competition

UK

A Thin Place, Fergus Carmichael, 2019, 12’16”, International Competition

Amaryllis – a Study, Jayne Parker, 2020, 07’00”, International Competition

Dungarees, Abel Rubinstein, 2019, 05’30”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Hacer Una Diagonal Con La Musica, Aura Satz, 2019, 10’20”, International Competition

Hard, Cracked the Wind, Mark Jenkin, 2019, 17’18”, International Competition

Our Largest, Marcus Forde, 2019, 05’32”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Turning, Linnéa Haviland, 2019, 01’50”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

UK/Germany

Junkerhaus, Karen Russo, 2019, 07’30”, International Competition

USA

A Song Often Played on the Radio, Raven Chacon/Cristobal Martinez, 2019, 23’25”, International Competition

A Month of Single Frames, Lynne Sachs, 2019, 14’12”, International Competition

Furthest From, Kyung Sok Kim, 2019, 18’58”, Children’s and Youth Film Competition

Hampton, Kevin Jerome Everson/Claudrena N. Harold, 2019, 06’00”, International Competition

Isn’t it a Pity, Heather Trawick, 2019, 07’50”, International Competition

South Korea/USA

Latency/ Contemplation 6, Seoungho Cho, 2020, 06’51”, International Competition

Vietnam/Taiwan

không đề #2 (untitled #2), Nguyen Anh Tu Pham, 2019, 03’02”, International Competition

* Not running as part of the online festival.

https://www.kurzfilmtage.de/en/festival/competition-selection/

https://www.kurzfilmtage.de/en/festival/sections/international/

May 2020

We Are Moving Stories

Sarasota Film Festival 2020 – Film About a Father Who

We Are Moving Stories is the world’s largest online community for new voices in film. We have introduced more than 2500 films to new audiences! We broadcast, embrace and support new voices in drama, documentary, animation, web series, women’s films, LGBTQIA+, POC, First Nations, scifi, horror, environmental and world cinema. We also connect films to causes, audiences, producers, distributors, sales agents, buyers, film festival directors and media. And here’s a good news story – over 50%+ of our contributors are women. Our profiles describe the passion, strength and intelligence filmmakers need for their films to reach an audience.

Between 1984 and 2019, filmmaker Lynne Sachs shot a film with her father, a bohemian businessman who sometimes chose to reveal less than was really there.

Interview with Director Lynne Sachs

Congratulations! Why did you make your film?

Since I began making films, I’ve been collecting material for a film about my father. It took me three decades to complete this film. Life goes on, and each day brings surprises, joys and disappointments. In 2020, I premiered Film About a Father Who at Slamdance and then at Documentary Fortnight at the Museum of Modern Art. This is the third film in my trilogy (including States of UnBelonging, 2005, and The Last Happy Day, 2009) of essay films that explore the degree by which one human being can know another. This film is a partial portrait of my father Ira Sachs, a bohemian businessman living in the mountains of Utah. My father has always chosen the alternative path in life, a path that has brought unpredictable adventures, nine children with six different women, brief marijuana-related brushes with the police and a life-long interest in doing some good in the world. It is also a film about the complex dynamics that conspire to create a family. There is nothing nuclear about all of us, we are a solar system comprised of nine planets revolving around a single sun, a sun that nourishes, a sun that burns, a sun that each of us knows is good and bad for us. We accept and celebrate, somehow, the consequences.

Imagine I’m a member of the audience. Why should I watch this film?

Over a period of 35 years between 1984 and 2019, I shot 8 and 16mm film, videotape and digital images of my father. Film About a Father Who is my attempt to understand the web that connects a child to her parent and a sister to her siblings. With a nod to the Cubist renderings of a face, this exploration of my father offers simultaneous, sometimes contradictory, views of one seemingly unknowable man who is publicly the uninhibited center of the frame yet privately ensconced in secrets. In the process, I allow myself and my audience inside to see beyond the surface of the skin, the projected reality. As the startling facts mount, I, as a daughter, discover more about my father than I had ever hoped to reveal. Over the last few months since the film’s Slamdance Premiere, I have had some of the deepest most intense interactions of my career as a filmmaker with people in my audiences. These conversations have allowed me to see the ways in which this film stirs viewers into thinking about the imprint their own fathers and mothers have had on who they are in the world today.

How do personal and universal themes work in your film?

Weighing the importance of the personal in relationship to the universal was an absolutely critical aspect of the editing process for this film. I had to search for a universality from my particular experience while weeding through 35 years of film, video and digital material. This was a critical journey to finding a way to tell this story. When I finally brought artist and editor Rebecca Shapass into my process, I found a way to convey the story of my family to a new person who knew nothing about us, had no expectations, prejudices or affinities. Through her sensitive, compassionate listening ear, I was able to carve out the kind of distance that allowed me to see that this was not really a character-driven portrait of one man but rather an investigation into the way that “family” is really just a term describing the intricate, sometimes heart-breaking series of relationships that hold a group of people together in a cosmos.

How have the script and film evolved over the course of their development?

In 2017, I gathered all nine of my siblings together for the first time. We shot for four hours, and the experience was, for the most part, cathartic. But, as I looked through the footage I noticed that everyone was extremely aware of how I, in particular, responded to their words. It took me a year to accept that this singular, more contrived, scene was significant in terms of who was there in the same room but did not take the film to the place I needed it to go. Throughout 2018, I either flew my siblings to Brooklyn or went to meet them where they live. In almost every case, I convinced my sisters and brothers to go into a completely darkened space with me. We often sat in closets. It was weird and very intimate. As I recorded their voices, resonating through my headphones, I knew I was listening to them in a deeper way than I had ever done before. There in the dark, they each accessed something new about our father that they had never articulated before.

One of the biggest and most intimidating aspects of making this film was finding a way to translate my own interior thoughts – be they loving, rage-filled, compassionate or simply contradictory – about our father into a convincing, not too self-conscious voiceover narration. From the very beginning, I knew that Film About a Father Who would be an essay film that would include my own writing. One of the reasons the film took so long to make was that every time I sat down to put a pen to paper, I became intimidated by the process. During an artist residency at Yaddo, I plopped myself on my bed with a bunch of pillows, and began to speak into a microphone. Over a period of 10 days, I recorded hours of material – oral histories, in a sense – that were generated by me as daughter, artist and director. To my surprise, I was actually able to apply the newly discovered “in the dark” approach to recording with my siblings to the way that I listened to my own thoughts and this more spontaneous vocalized writing became the framework for the whole movie.

What type of feedback have you received so far?

This film has probably generated some of the most interesting, deeply felt responses I have ever received for my work. Here are a few, I would like to share:

“The film is bookended with footage of Lynne Sachs attempting to cut her aging father’s sandy hair, which — complemented by his signature walrus mustache — is as long and hippie-ish as it was during the man’s still locally infamous party-hearty heyday, when Ira Sachs Sr. restored, renovated and lived in the historic Adams Avenue property that is now home to the Mollie Fontaine Lounge. ‘There’s just one part that’s very tangly,’ Lynne comments, as the simple grooming activity becomes a metaphor for the daughter’s attempt to negotiate the thicket of her father’s romantic entanglements, the branches of her extended family tree and the thorny concepts of personal and social responsibility.” – John Beiffus, Memphis Commercial Appeal

“A Film About a Father Who is also remarkable for its terrific synthesizing of the wealth of archival material. Given the breadth of the narrative span, it’s extraordinary that the director fits the story into a compact length of just 73 minutes, yet, masterfully, she does. Given her extremely personal connection to the story, it’s astonishing how deeply she investigates the good and the bad in a person she clearly loves. This gripping documentary, the opener of the 2020 Slamdance Film Festival, speaks its truth and speaks it beautifully. Let it be heard.” – Christopher Llewellyn Reed, Hammer to Nail

“Film About a Father Who is simply a masterpiece. Ultimately, a parent’s legacy is found in their children and the worth of Ira Sachs Sr. is found in his “tribe” of talented, artistic offsprings.” – Nina Rothe, E. Nina Rothe.com

“In this compelling and genuine documentary, [Sachs] has…taken the audience on a hypnotic and profound journey.” – Alexandra Hidalgo, Agnès Films

“Lynne’s newest, Film About a Father Who, brings that unflinching honesty to a new level. Because this is a personal story told by the children forced to come to terms with his behavior, preserving that ambiguity also, as Lynne herself puts it, preserves the truth. Both Lynne and we are perhaps no closer to understanding Ira Sr. by film’s end, but we at least know him as his children do and all things considered, that’s nothing short of miraculous.” – Mariso Carpico, The Pop Break

Has the feedback surprised or challenged your point of view?

Even during the film’s years-long protracted post-production, I was always scared and somehow motivated by my awareness that there would be extremely strong reactions to my film. My portrait of my father is one that includes my own rage and forgiveness, and finding the balance between the two was integral to expressing my own experience through the film’s images and voice-over narration. There have been a surprisingly large number of people who have written about the film or written to me directly about the film who have had similarly complex and fraught relationships with their own parents. It seems that watching “Film About a Father Who” gave them some new insight and perspective. There have also been other people who felt that I, as a woman, gave my dad too much of a break, that I was too kind to him when he only considered his own needs and desires rather than those of others around him. This point of view is reflective of the sentiments that have grown out of the women’s movement and more recently the Me-Too Movement. I feel such allegiance to these emotions, and yet when it came down to expressing my own experience, I had to allow for the nuances of a daughter’s own evolving love for her father.

What are you looking to achieve by having your film more visible on www.wearemovingstories.com?

I would love for the visibility that We Are Moving Stories provides to lead to new conversations, surprising insights, future screenings and maybe a distributor!

Who do you need to come on board (producers, sales agents, buyers, distributors, film festival directors, journalists) to amplify this film’s message?

The film has quite a few upcoming festival screenings including Sarasota Film Festival, Indie Memphis, Sheffield Doc Festival in the UK, Montreal Documentary Festival, and Oxford Film Festival, but the pandemic has, of course, slowed everything down. I could definitely use some support from sales agents, buyers, programmers or distributor. Let’s talk!

What type of impact and/or reception would you like this film to have?

While I have been making films for more than thirty years, each film I have made has led to a new relationship with a certain community. My film Your Day is My Night led me to the Asian and Asian-American community in the US, Canada and China and to a far deeper relationship with people living in Chinatown right here in NYC. My film Carolee, Barbara and Gunvor has led to amazing conversations around feminism, cinema and the avant-garde. We make films to lead us to new places, physically, artistically and emotionally. With Film About a Father Who I hope to go deep in conversation around family, rage, and forgiveness.

What’s a key question that will help spark a debate or begin a conversation about this film?

In light of the current Me Too debate around men in power and their influence on the lives of the women around them, how can we find a context by which we can discuss the place of rage, dignity, and forgiveness?

Would you like to add anything else?

Thank you for inviting me to be part of your cinema community.

What other projects are the key creatives developing or working on now?

Lynne Sachs is currently working on Oh Ida: The Fluid Time Travels of a Radical Spirit, an essay film that will trace the erasure and recent emergence (in the form of monuments) of the story of activist and 2020 Pultizer Prize winning journalist Ida B. Wells who spent her early years in my hometown of Memphis, Tennessee and committed her life to nurturing a spirit of liberation in the face of resounding oppression. In collaboration with historian and author Tera Hunter, I will produce a film using a hybrid form of cinematic time-travel that will examine Wells’s historical trajectory within the current controversies around American monuments by looking at their symbolic power, their historiographic influence on our collective consciousness, what they have been and what they could become.

We Are Moving Stories embraces new voices in drama, documentary, animation, TV, web series, music video, women’s films, LGBTQIA+, POC, First Nations, scifi, supernatural, horror, world cinema. If you have just made a film – we’d love to hear from you. Or if you know a filmmaker – can you recommend us? More info: Carmela

Film About a Father Who

Between 1984 and 2019, filmmaker Lynne Sachs shot a film with her father, a bohemian businessman who sometimes chose to reveal less than was really there.

Director: Lynne Sachs

Producer: Lynne Sachs

Writer: Lynne Sachs

About the writer, director and producer:

LYNNE SACHS makes films and writes poems that explore the intricate relationship between personal observations and broader historical experiences. Her work embraces hybrid forms, combining memoir, experimental and documentary modes. Recently, she has expanded her practice to include live performances.

Key cast: Ira Sachs Sr.

Looking for: sales agents, distributors, journalists, film festival directors, buyers

Facebook: Film About a Father Who

Twitter: @aboutafatherwho

Instagram: @lynnesachs1

Hashtags used: #filmaboutafatherwho

Website: www.lynnesachs.com/2019/12/19/filmaboutafatherwho/

Funders: Partially supported by an artist residency at Yaddo.

Where can I watch it next and in the coming month? The film is not streaming again in the coming month but it will be presented at Indie Memphis, Oxford Film Festival, Montreal International Documentary Festival, and Sheffield International Festival of Documentary Film.

http://www.wearemovingstories.com/we-are-moving-stories-films/2019/1/17/film-about-a-father-who

May 1, 2020

Chapter 16 – A Community of Tennessee Writers, Readers & Passersby

Book Excerpt: Year by Year

About Chapter 16

In response to the loss of book coverage in newspapers around the state, Humanities Tennessee founded Chapter 16 in 2009 to provide comprehensive coverage of literary news and events in Tennessee. Each weekday the site posts fresh content that focuses on author events across the state and new releases from Tennessee authors. In addition, Chapter 16 maintains partnerships with newspapers in each major media market statewide, and our content appears in print each week through the Memphis Commercial Appeal, the Nashville Scene, and the Knoxville News Sentinel. Through the site, social media, a weekly newsletter, and our newspaper partnerships, Chapter 16 reaches more than half a million readers on a good week.

When filmmaker Lynne Sachs turned fifty, she dedicated herself to writing a poem for every year of her life, so far. Each of the fifty poems investigates the relationship between a singular event in Sachs’ life and the swirl of events beyond her domestic universe.

In May 2020, Chapter 16 featured a “2010” from the collection of 50 poems.

In the eventuality that preparation for security advanced

signatures obtained life jackets confirmed permanent medical

records sealed pharmaceuticals delivered weather reported

batteries checked tires filled expiration avoided warnings

acknowledged wills signed if-and-only-ifs collected and still

no one anticipated the return of my brother-in-law’s cancer.

A friend forgot to send her payment — a single check

she never put in the envelope, hidden under

a stack of receipts, appointment cards, and electricity bills.

The check, never arrived. Her policy, cancelled.

She who had already given up her ovaries and come

face-to-face in the ring with illness, won that round.

Now no rope to hold onto, no pillows to fall back on.

We two friends of more than twenty years sit at a table

in a café talking of our homes, books we’ve read,

people almost forgotten, purses with zippers, jump

ropes, kitchen counters, projects abandoned.

I ask her about her health. She’s crossing her fingers

That’s all she has until they pass that bill.

https://chapter16.org/2010-2/?fbclid=IwAR2MzQODqLHB7begl6f87tkKXb2GgeTG7cAEGmTHJew-o8f-tVGO0qiGCko

“In Lynne Sachs’ FILM ABOUT A FATHER WHO she tries to piece together who her father really is…and makes some unexpected discoveries. An intriguing puzzle – so don’t let anyone who sees it reveal its secrets.”

Steve Kopian, Unseen Films

Watch Film About a Father Who here through May 10th!

There will also be a Q & A with the director online soon.

“Taking visual cues from modern art, and a title borrowed from Yvonne Rainer’s 1974 drama “Film About a Woman Who…,” Lynne Sachs compiles a film that’s as colorful, as complex, and sometimes as inscrutable as her father. She may not have unlocked the secret of her father’s heart, but the attempt reveals touching, humorous and painful insights about what we think a father is and what he should be.”

-Sean P. Means, Movie Cricket

In response to popular demand from the Sarasota community and audiences across the country and around the globe for continued arts and storytelling, the 2020 virtual edition of the Sarasota Film Festival (SFF) has now extended its online edition to Sunday, May 10th. In conjunction with this extension, the festival has announced an additional feature film to the lineup 9/11 KIDS directed by Elizabeth St. Philip, Q&As for the upcoming weekend, and more visionary programming.

“The public has spoken and in an effort to continue providing dynamic and thoughtful entertainment, we are pleased to extend our programming for an additional week so that audiences can continue to enjoy these engaging films and celebrate independent storytellers that showcase the local Florida community,” said Mark Famiglio, Chairman and President of the Sarasota Film Festival.

SFF is presented with the generous support of various sponsors and partners from the Sarasota community including: The Famiglio Family, Amicus Foundation, 332 Cocoanut, Moon & Co Eyewear, Sage Restaurant, The Sack Family, Wallack Family Fund, Sarasota County Film & Entertainment Office, New College, Ringling College, Gates Construction, DSDG architects, BMW/Lamborghini of Sarasota, Embassy Suites-Hilton as well as granting organization Sarasota County Tourist Development Cultural/Arts and the Florida Division of Cultural Affairs.

EXTENDED DATE | SFF will now run through Sunday, May 10th, 2020.

May 5, 2020

Episode 4 – Experimental Lynne Sachs Takes the Mic

It was my pleasure to interview experimental filmmaker Lynne Sachs. Her body of work is not only vast, but her depth of knowledge of filmmaking and filmmakers is nothing short of phenomenal. Lynne is one of those rare filmmakers who you wish you could have known and worked with for the past 20 years. I love her films, her energy, and her enthusiasm for experimental film. Her work has screened at major museums. She has taught film at NYU. And her list of accolades, fellowships, collaborations, and experience rivals that of any of the now classic experimental filmmakers. You can see more of her work at lynnesachs.com.

In this episode, Lynne and I talk about several of her films, her work with Barbara Hammer, Carolee Schneemann, and Gunvor Nelson. We talk about her process, her cameras, and some specifics in her work. Once you listen to the podcast and check out her films, you’ll find out why I’m her newest (and perhaps biggest) fan.

http://experimentalfilm.info/episode-4-experimental-lynne-sachs-takes-the-mic

April 30- May 2, 2020

The 17th Annual Iowa City International Documentary Festival

The Iowa City International Documentary Film Festival (ICDOCS) is an annual event run by students at the University of Iowa. Our mission is to engage local audiences with the exhibition of recent short films that explore the boundaries of nonfiction filmmaking. We seek innovative new works of 30 minutes or less that both complicate and expand upon conventional approaches to nonfiction and documentary.

COMPETITIVE PROGRAM #6 – A Primal Scream

I Can’t / Lori Felker / US / 2020 / 5:00/ Silent – A roll of film is not a successful conduit for grief.

SIR BAILEY / Matthew Ripplinger / Canada / 2018 / 8:00 – A portrait of the filmmaker’s old friend. The film’s surgical cutting and state of decay symbolizes Bailey’s suffering of bone cancer, consisting of home made photographic emulsion, contact printing, and reticulation. Sir Bailey embarks on an existential journey through the shattering photo-chemical plane during his last day of life.

LIMEN / Kathryn Ramey / US / 2019 / 2:06 – Threshold. At the boundaries of perception. Between one state and another.

Ascensor / Adrian Garcia Gomez / US / 2019 / 8:02 – Ascensor is an exploration of grief, longing and mysticism through a queer lens. It documents a syncretic ritual that culls from the magical reverberations in Mexican culture to process the unexpected loss of a dear friend. The repetition of the ritual eventually leads to the transcendence of physical space, transforming unrelenting ache into shining resilience. Philip Horvitz 1960 – 2005

A Month of Single Frames / Lynne Sachs with and for Barbara Hammer / US / 2019 / 14:00 – In 1998, filmmaker Barbara Hammer had an artist residency in a shack without running water or electricity. While there, she shot film, recorded sounds and kept a journal. In 2018, Barbara began her own process of dying by revisiting her personal archive. She gave all of her images, sounds and writing from the residency to filmmaker Lynne Sachs and invited her to make a film with the material. Through her own filmmaking, Lynne explores Barbara’s experience of solitude. She places text on the screen as a confrontation with a somatic cinema that brings us all together in multiple spaces and times.

Pilgrim / Cauleen Smith US / 2016 / 11:00 – A live recording of an Alice Coltrane piano performance accompanied by a visual track that documents a pilgrimage across the USA taken by Cauleen Smith, tracing historic sites of creativity and generosity that were an inspiration to her: Alice Coltrane’s Sai Anantam Ashram; the Watts Towers; and the Watervliet Shaker Historic District.

https://icdocs.wordpress.com/icdocs-2020-copy/

By Andrew Key

Roland Barfs

April 14, 2020

https://rolandbarfs.substack.com/p/she-observes-herself-and-others-learning

A Year in Notes and Numbers (2017) is a 4 minute silent digital video work by the American experimental filmmaker Lynne Sachs, which consists of close-up shots of a few words from to-do lists and notes to self, mostly written on yellow ruled paper, with names, errands and artistic intentions written in various coloured inks, circled, crossed out, stained, creased, blotted: “Write Mom / to thank!”; “Vitamin D”; “FROGS”; “Make 2 shelves / Build 2 shelves”; “lightbulbs”. These lists are occasionally overlaid with medical terms and measurements: “Sodium / 138”; “Globulin / 2.6”; “eGFR / 86”. At one point a section from the production notes of what is probably one of Sachs’ other films is shown: “She observes herself / and others // learning”. The next shot: “Camera as extension of her body.” The next shot: “Fun of research.” We see the minutiae of a year in a life, the endless small tasks that demand to be completed, correspondence that needs to be written, plans and ideas for projects that might or might not be realised; we also see the medical quantification of the body which performs these tasks. There are personal reminders: “Write Barbara H” (Barbara Hammer, presumably); there are political reminders: “Get out the vote”. It ends with the word “Mom”, then the figure “125 LBS”, then a few seconds of swirling reds, yellows and greys.

A Year in Notes and Numbers relates to a strand in Sachs’ earlier work, which goes right back to one of her earliest films, Still Life with Woman and Four Objects (1986). These pieces are distinct from, but related to, the experimental documentaries about political history which Sachs has also made, and focus more closely on everyday life and its reproduction. In Still Life with Woman and Four Objects—a tribute to the anarchist and feminist Emma Goldman—a woman puts on a coat, peels and pits an avocado, suspends the stone above a glass of water to sprout it, eats a meal, and reads aloud a letter of Goldman’s. Food preparation, small acts of gardening, eating and anarcha-feminism all sit on the same level. This strand of Sachs’s work is perhaps best represented in a piece like Window Work (2000), a 9 minute sound video comprising of a single uninterrupted shot of a kitchen window in Baltimore, in which a women washes the windowpane, makes and drinks some tea, reads the newspaper. Two small frames within the larger image show miniature home-movies, which gesture towards personal memory and earlier media technologies: Super 8 film as the precursor to videotape. Window Work could be read as a kind of Jeanne Dielman (Chantal Akerman, 1975) in miniature; though where Chantal Akerman shows the drudgery and tedium of housework with an unflinching clarity, in Sachs’ film the accoutrements of domesticity are shown in shadow and used to evoke a dream-like atmosphere which encourages fantasy and reverie on the viewer’s part. Jeanne Dielman tries to make housework visible, or at least questions to what extent labour can be made visible through cinema, and in doing so, demands work from the viewer, who must pay attention, sitting through its lengthy run-time and long, slow takes. Sachs’ Window Work, on the other hand, is more playful with the concept of work—does the “work” in the title refer to the work of cleaning the window, in a fairly desultory fashion, or to the artwork we are watching? Is the work of this film a dreamwork?

In contrast to these earlier explorations of the everyday and domestic in Sachs’ oeuvre, A Year in Notes and Numbers is mundane on a different level. By showing names, tasks, numbers and stray thoughts completely devoid of any context, with no date or other clue as to what they mean, a year is condensed to a flurry of seemingly meaningless activity, combined with the equally decontextualised and slightly ominous medical statistics that appear intermittently on screen. Calcium: 9.6. Is this good or bad? Sinister or reassuring? What about Bilirubin 0.7? (According to Google, both of these figures are within the average range.) By reducing the representation of a body to written memoranda and biological measurements, this recent work by Sachs is somehow both more personal and more alienating than her earlier work dealing with similar topics. The body is reduced to a quantum of figures, abstracted into data, but not at the expensive of the person who that body is, who has family and friends to write to, lightbulbs to buy, DVDs to watch, interviews to listen to, films to make.

Unending Lightning (2015–ongoing) is a six-plus hour three-channel video installation by the Spanish artist Cristina Lucas which documents every aerial bombing over civilians since the development of manned flight. It visualises a database gathered by a large number of researchers and organisations, building on research begun in 2011, on the 75th anniversary of Guernica, arguably—thanks to Picasso—the most famous aerial bombing of civilians. Manned flight was made possible in 1903. By 1909, two people could fly in one aircraft. Aerial bombing began only two years later, in the 1911 Italo-Turkish war, a war over colonial control of Libya. Unending Lightning is an ongoing work, because it will only be complete when aerial bombing over civilians, including drone strikes, is a military strategy that has been abandoned. The central screen shows a map of the world with the locations of the bombings and the number of civilian casualties marked; the left screen shows the respective military forces responsible for dropping the bomb, the type of bomb dropped, the city bombed and the known number of casualties; the right screen shows archive and documentary videos and photography from the aftermath of the bombings. I saw it at Manifesta 12 in Palermo, where it was shown in the Casa del Mutilato, a hospital for wounded soldiers designed by the Rationalist (i.e. Fascist) architect Guiseppe Spatrisano in 1936: a large temple to fascism erected in honour of the Italian annexation of Ethiopia in the same year—a conflict which saw Italy using poison gas bombs on Red Cross hospitals. As Sven Lindqvist argued in A History of Bombing, in its first years aerial bombing was seen as a convenient and exciting answer to the question of how exactly European powers could exterminate entire populations without having to get their hands quite so dirty. The origin of this technology lies in colonial violence.

Unending Lightning is a magisterial work, one requiring a collaborative team of researchers and software engineers, the accumulation and maintenance of large amounts of historical data; it is open-ended and so almost unwatchable as a single piece, with a runtime which grows with each new drone strike in Afghanistan (almost 40 per day in September 2019 alone, according to The Bureau of Investigative Journalism). The visual aesthetics of Unending Lightning resemble nothing more than a PowerPoint presentation: bullet-pointed information presented in Helvetica on grey-blue backgrounds, grainy historical photographs gradually improving in quality as the work moves closer to recent bombings and the video and photography technologies which captured the aftermaths develop. While watching it, the viewer sees the unceasing global conflicts which have unfolded over the last century and more. Near the beginning of the film there are a few moments where days go by in which no aerial bombings take place, but soon it is every day, all over the globe, often accompanied by the phrase “unknown numbers of civilians killed”. Even with the enormous amount of research undertaken for the work, we will never be able to truly know through quantification the amount of death unleashed on the world by the advent of bombing from the air.

What does Unending Lightning have to do with Lynne Sachs? At first glance perhaps very little. But they operate at different ends of the same recent aesthetic tendency, exploring quantification and its limitations. In Lucas’ work, we watch something unfold which feels like an unending depiction of death and destruction, mostly of women and children; what necessarily gets left out of the work, and as such is brought concertedly to mind when we view the piece, are the actual everyday lives of the people who were killed by these bombs dropped from the air. In Sachs’ recent work, on the other hand, the abstraction of a life from a record of its daily activities asks the viewer to fill in the gaps, to imagine or project something into the space that is left open between the unfinished errands and the medical figures we are presented with. In very different ways both artists are concerned with the everyday, the way that developments in technology can start to feel familiar, natural, normal, until all of a sudden they don’t, and they erupt into the sphere of domesticity, whether that’s through the collection and retention of biological data by private healthcare companies, or the firing of a missile from a remote-controlled drone.

May 2022

https://rolandbarfs.substack.com/p/roland-barfs-film-diary-weeks-2021?utm_source=email&s=r

Lynne Sachs’ work mentioned in conversation with the work of Anne Haugsgjerd. You can watch her film “Life in Frogner” below:

As always, please consider subscribing, or buying me a coffee or commissioning me to write about a film. If you like the diary and you can’t support me financially at the moment, please share it with a couple of people you know who might like it. And feel free to get in touch if you want to talk about any of the films I write about, or want to tell me about some other films you think I might like. Thanks again!

+ Also: I recently appeared on a podcast, PRISMS, in Oslo, talking about the film diary, my thinking behind it, why I do it, how I feel about it, etc. You can listen to that here if you’re interested. +

roland barfs film diary weeks 20–21

terminal usa, life in frogner, oedipus rex, mission: impossible – fallout, vampyr, after hours

May 11. Wednesday. I have been having stomach issues for the last few days that show no sign of abating. I’ll spare you the details, gentle reader. I haven’t been eating very much and I have been avoiding caffeine and alcohol, those usual stalwarts, and I feel exhausted and run-down and fairly miserable. I worked from home yesterday but think I need to show my face in the office today, so I go in and have a few meetings, trying to ignore the waves of pain. I send some emails. I look at a lot of documents. After a few hours of this I decide I have been visible enough and I go home, where I immediately fall asleep for an hour. I wake up feeling a little better. In the evening I have an online safeguarding and boundaries training session, which is fine. After it’s over, Kate, Catherine and Tara come over for Film Club. L returns from work just after they arrive. It’s my choice of viewing. Earlier I spent some time trying to pick something but felt overwhelmed by both the endless choice of films available and by my sense of cinematic fatigue, which is still with me. I am not capable of watching a lengthy film this evening, so I end up choosing Terminal USA (dir. Jon Moritsugu, 1993).This is a sixty minute made-for-TV schlockfest that was a focal point of one of the semi-regular right-wing protests against taxpayer’s money being used to fund public television in the US: conservatives were disgusted that their constituents’ hard earned bucks were being spaffed away on garbage like this, which was funded by PBS. In fact, when the film was submitted to PBS for distribution, only two thirds of stations agreed to show it, because so many programmers and audiences found it beyond the pale. Of course, all this only adds to its allure for me, and I am delighted by Terminal USA, which is an accomplished work of 90s slacker black humour, a wholesale attack on the nuclear family and the idea of Asian-Americans as a model minority. It’s a combination of John Waters, Gregg Araki (who is thanked in the credits) and Dennis Cooper, exploring and revelling in a wide array of social bugaboos: drug abuse, male impotence, religious apocalypticism, teen pregnancy, pre-marital sex, unseemly voyeurism from pimply pizza delivery boys, queer erotic fantasies about musclar fascist skinheads stomping on your face, disrespect for the elder generations, sexually ambiguous bleach-blond perverts dressed as vicars and toting firearms, and the violation of the moral sanctity of cheerleaders. It is cheap and gross and stupid and sloppily made, it looks and sounds kind of half-assed and rushed, and the acting is so off-tempo and stoned that it feels like everyone present inhabits their own separate universe. It unravels into a complete shit-show, ending with the deus ex machina of a character being beamed up to an alien spaceship. At one point some skinheads (one of whom is played by Gregg Turkington) erect a burning cross in a family’s front yard, soundtracked by classic DC hardcore band Void. It’s a highly kitsch and camp punk film, which surely would have only been a source of frustration, bafflement and disgust for the majority of people who happened to catch it on TV in 1993. I really enjoy it. I’ve not seen anything else by Jon Moritsugu, but I’m very keen to check out more of his work, which includes delightful titles like Mod Fuck Explosion, Pig Death Machine, Sleazy Rider and, most winningly of all, Mommy Mommy Where’s My Brain, a short which is described as half AC/DC, half Derrida. Terminal USA is a joy: totally uproarious garbage. Well worth going out of your way to find a copy (I didn’t watch it there, but apparently it’s now available on the Criterion Collection, so you don’t even have to look too hard).

May 17. Tuesday. A warm day which I mostly spend indoors. My new schedule dictates that I should normally be at work today but, for reasons too boring to type out, I’m not. I have nothing pressing to do, and so I spend the day mostly in a state of anxious uncertain tension, trying to decide what to do with myself. I send some emails. I look out the window. I don’t really manage to concentrate on anything and feel the old muddy worry about squandering my life start to bubble away. At midday, I walk to the bank down the road and hand them the letter addressed to them which I found lying in the street yesterday. My good deed done, I scurry back inside. I eat some asparagus and a poached egg for lunch. L is marking. Mike sends me a link to the podcast about this diary that we recorded yesterday; I’m not in the right state of mind to listen to myself talk so I text Catherine and ask her to listen to it for me — she assures me that I come across well in it: ‘thoughtful’. Good enough for me. I’ve been trying to avoid social media recently because it’s been making me depressed, or compounding my recent spell of depression, or both, more so than usual anyway, but I sign in to share a link to the podcast, and then I get sucked into a few more hours of dreary procrastination. It clouds over outside and I feel a little better about being inside. Mid-afternoon, I decide that I’ve had enough of this state of mind and want to get on with something useful. I watch Life in Frogner (dir. Anne Haugsgjerd, 1986), which Mike has commissioned me to write about for PRISMS. This turns out to be perfectly suited to today’s mood of distraction and despondency, and it makes me feel a little less isolated in my procrastination, which is nice. It’s a short film, 22 minutes or so, about Anne Haugsgjerd’s efforts to sit down and write a script for a film about Frogner, the district of Oslo in which she lives. She sits at a typewriter, drinks some coffee, smokes, gets up, tidies her desk, sits back down, gets up again, cleans her windows, watches a woman sunbathing across the street, watches some people walking dogs on the street, sits back down, starts typing, stops typing, puts her head in her hands. This, I read, is Haugsgjerd’s first film, and I find this information very pleasing, satisfying in the familiar note of understanding it strikes. What better way to announce your arrival as an artist than by expressing your incapacity to create art? The doubts, the distractions, the lack of focus and the false starts, the blinding whiteness of the blank page, the struggle to just sit down and actually get on with it: surely the universal experience of the artist-manqué. Obviously, I’m sympathetic to this strategy of defeating the block by embracing the block, partly because I used it to get my own first novel written, and it seems to have worked well enough there. But Haugsgjerd’s exploration of her failure to move forwards in her work also speaks to the aesthetic strategies I’ve employed in writing this diary, and I feel gratified to have this part of myself reflected back at me. I am always reluctant to describe things as ‘relatable’ — doing so is cheap and easy and doesn’t say anything meaningful or interesting about the work, often merely serving to express the critic’s own narcissism — but I find Life in Frogner very relatable, narcissist that I am. There are a few stylistic elements that remind me of other films, of course — a couple of shots that make me think of Lynne Sachs, a little hint of Varda in some of the meta-textual humour of the film — but the style feels very assured and clear, particularly considering it’s a debut. The tension explored in the film between the observation of life and participation in it, the impossibility of simply being a spectator, and the anxieties and regrets that emerge from trying to mediate your whole life through an artistic practice: all of these feel particularly sharp for me, and I am impressed with the openness and vulnerability with which Haugsgjerd explores them.“Life is everywhere, life is outside your window. Life is pulsating there as you’re trying to write about life. … You should have lived that life instead of making film at all.” There’s a kind of wry, amusing edge to the film, a playfulness which stops it from feeling too heavy-handed or self-serious, which demonstrates an awareness that the writer struggling in front of their typewriter is, ultimately, a comic figure. And this tone makes the closing sentiment of the film, an expression of optimism in the face of artistic doubt, even more resonant for me: “I am both shy and an exhibitionist at the same time. That’s the conflict in me, but I think it’s about exposing yourself. I think if you do that you will always find someone out there that will understand.” It’s a risk, but there’ll be someone who gets it. Comforting words. You can find Life in Frogner on Vimeo. A really lovely little film.

Afterwards, I write the above entry. L goes to Lincoln. It starts raining. I engage in the shameful form of active time-wasting which has recently absorbed my life: playing The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild on the Switch that I’ve borrowed from Catherine. This is partly to blame for the last week or so of my not really watching any films, compounding the previous feeling of burnt out apathy. I haven’t played video games for a long time, other than fairly infrequent occasional grubby bursts of Civilisation V, which I think I’m now well and truly done with. Immediately with Zelda I feel fully immersed back into the atmosphere of sweaty compulsion and addiction. It is kind of horrendous how effective it is at sucking up time: two, three hours can pass without any sense of accomplishment or even pleasure. It’s weird and I feel very ambivalent about it. Tonight I manage to restrain myself to playing for 90 minutes. Then I pull myself together and watch Oedipus Rex (dir. Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1967). I’ve not seen it before and I watch it partly out of a stirring of the completionist urge towards PPP. I feel like this is one of the few Pasolini films which I very rarely see anyone saying very much about. Out of his other works it’s unsurprisingly closest to Medea in terms of style, employing a similar visual salmagundi of elements lifted from various exoticised and appropriated national folk cultures: like Medea, Oedipus Rex takes place in a past which can actually be located both nowhere and nowhen, which is appropriate for a reworking of a Greek myth which sits at the foundation of Western culture. That said, the beginning and ending of the film are very clearly located in Italy: the film begins with the birth of a child to a bourgeois woman who is having an affair with a soldier in 1920s fascist Italy, and it ends with the child, Oedipus, blind and destitute, being led around the industrialised post-war Italian landscape, with a bunch of shots that feel more like Antonioni than anything else I can remember seeing in Pasolini. It’s the middle section, the bulk of the film, which takes up the riot of colour and costume and various musical borrowings from cultural ethnographies that we also see in Medea. I think I like it a fair amount but probably not as much as I like Medea. It’s actually quite a challenging and uneven film and I feel more ambivalence about it than I usually do with Pasolini, who, in all honesty, I am usually pretty uncritically positive about. I don’t know if this is really a success or not, but it’s still worth watching. I think of a few other films while I’m watching it, neither of which is very similar at all to Pasolini’s Oedipus Rex, but which perhaps can help situate my experience of the film in a kind of Venn diagram: it’s somewhere between Buñuel’s Simon of the Desert and Piavoli’s Nostos: The Return, maybe. I’m very interested these days in reworkings and modernisations of Greek myth, thanks to my efforts to work on The Bacchae, and I feel like there is a lot here I find useful for that purpose. I don’t feel entirely satisfied when it’s over, but I think the problems I had with it — which, to be frank, have kind of dimmed in the few days between watching it and writing this — are actually generative in some way. One thing I particularly enjoy is the film’s total lack of interest in continuity: when Oedipus is still a baby he is depicted by at least four different children, who barely look alike at all, sometimes switched half-way through a scene. I love this. Who cares what the baby looks like, that isn’t the point of this film, a baby is a baby is a baby, this is a story of the universal psychological conflict which affects everyone whether they want to accept it or not. I feel like I should have more to say about Oedipus Rex, maybe something which takes advantage of the very ready-to-hand psychoanalytic engagements available to me, but I’m going to stop there. If you’ve read Freud and then you watch this it all feels pretty familiar and clear anyway. I’m glad to have gotten to it, but I don’t know if I’ll be rushing to watch it again any time soon.

May 21. Saturday. Will is visiting. Last night we went to the Rutland, where we met Kate, Catherine and L, who left us to go and watch Everything Everywhere All At Once. Will and I did not go to see it, but kept drinking and ended up having a long conversation with one of my ex-colleagues from the care home who I ran into by chance. Afterwards, L, Will and I stay up until 2:30 watching music videos on YouTube. Today we are not moving very quickly. We go get some croissants and coffee and sit outside for a bit. We go to Kollective for lunch with Kate and Catherine, and then go for a drink at the Dorothy Pax, next to the canal. Then we walk up the canal in the sun to Attercliffe, where we go to St Mars of the Desert; a new experience for everyone. It’s nice. The weather is pleasant. We spend the afternoon drinking and then get a taxi home. Kate and Catherine rejoin us after a brief hiatus, and we order pizza from Napoli Centro and then watch Mission: Impossible – Fallout (dir. Christophere McQuarrie, 2018). L and I saw this in the cinema when it came out; a 10am Sunday screening at Duke’s at Komedia in Brighton with a hangover, and it was a really excellent experience. We choose to watch this I guess partly because we’ve all seen Tom Cruise’s recent comments at Cannes being shared over and over: when asked why he feels the need to do all the stunts that he does, he replies, smugly, that nobody asked Gene Kelly why he danced. An incredible answer. I perhaps don’t really explore the depths of my feelings about Tom Cruise very often, but I really am starting to believe that he’s among the greatest actors alive. He’s not very versatile and he’s certainly never complex, but he has heroically embraced his limitations and understood his skills completely, and he’s never boring to watch, never mediocre or half-assed. Tom Cruise is always giving everything to his work, and I always enjoy watching him. The whole Scientology is whatever; I feel like we can move past that — we all know about it, and it’s fucked up, but he’s still a completely eccentric genius, whose strangeness only gets more intense the more actively he pretends that he’s in any way a remotely normal person. The Mission: Impossible franchise is some of his greatest work, and Fallout is a hugely entertaining piece of cinematic exuberance. Henry Cavill, who I generally think is hugely dull and tedious to watch, is perfectly cast here as a bland evil CIA agent who becomes Cruise’s antagonist. In the big climactic helicopter chase with which the film ends there are some great shots of Cavill just sitting staring blankly into space as Cruise tries to crash another chopper into him: the lack of any spark of intelligence or engagement with the world behind Cavill’s eyes, the deadened glaze of an animatronic plank of wood, are some of the funniest moments in a film which is filled with hilarity. Another great moment is right after Tom Cruise’s emotional reconnection with his ex-wife, when we get to see Tom sprinting away in the background, both arms pumping at full velocity. I would prefer if Simon Pegg wasn’t in this film but it’s quite useful to have such an easy target for any irritation I feel with the film: all blame for any lack in Mission: Impossible – Fallout can be placed at Pegg’s feet and then be forgotten about. It’s a riot. Everyone in the room is shrieking and yelling, we’re all having a nice time, it’s genuinely thrilling and exciting even though we’ve all seen it before. Tom Cruise is a genius. I think I’ve got a long-read about him bubbling away, so if anyone wants to commission that for a publication please let me know and I can give you 20,000 words of hagiography in less than a week.

May 22. Sunday. Will is still here. We go get a sausage sandwich from the café in Endcliffe Park and then walk to the coffee van in Bingham Park. Will and I eat some cannoli on a bench. We come home and L and Will play video games for a little while. Then we walk into town and go to Showroom, where we see Vampyr (dir. Carl Theodore Dreyer, 1932). None of us have seen it before. I’m pretty sure I’ve not seen Dreyer’s Joan of Arc but something in the back of my mind is telling me that I watched it in a depressive funk in either 2017 or 2018, before I started the diary. Which would make sense, and perhaps having seen it and then forgotten everything about it is further justification for continuing this project, so I can keep track of what I watch in my various fugue states. Anyway, I have high hopes for Vampyr, although perhaps with a slight wariness: I am aware that I often find 1930s films, even the greatest films of the period, a bit of a tiresome slog, and I prepare myself to be a little bored. And maybe I fade in and out of attention a little but for the most part I’m pretty absorbed by Vampyr, which is much stranger and more uncanny than I’d anticipated. As Will points out afterwards, we’ve all seen the vampire myth explored on film a bajillion times, and there isn’t a huge amount here in terms of plot that isn’t very familiar, but with that taken for granted the viewer can focus their attention elsewhere: the extremely intense and odd visual style. This is a dream film, an unpleasant and jarring nightmare where images don’t always make sense in the way you would expect. There are a fair amount of visual effects which, despite being 90 years old don’t actually feel dated or overly familiar but really add to the feeling of uncanny nausea permeating the film. There are some shots filmed outside in a very very soft focus which are extremely grainy and quite challenging to make out any detail of the image and, rather than feeling like a kind of technical mishap, these feel like the kind of half-remembered half-recognised experiences that are otherwise only experienced in dreams. The use of doubling is particularly weird and disconcerting. The influence of these elements is absolutely transparent, particularly in the obvious surreal filmmakers like Buñuel and Lynch. Vampyr is not scary, exactly, but it is unnerving and confusing and unpleasant; the plot, freely adapted from a Sheridan Le Fanu text, is really just a canvas on which Dreyer and his cinematographers can create some very striking visual compositions. It’s an odd film. I suppose I feel a very clear divide during it between my deep and intense aesthetic enjoyment in the style and the cultivated boredom I feel about watching a 1930s horror film. But it’s good to see it, particularly in a cinema. At home I wouldn’t give it the attention it merits. I’m a little relieved when it’s over, and I probably would have liked it even more if I’d have a coffee before, but it feels like a very worthwhile experience: getting to see what horror was like before everyone had figured out what the genre should feel like. Apparently there was a riot when it first screened, with the audience demanding their money back because of how impenetrable it felt: clearly a sign of its brilliance.

After Vampyr we go for a beer at the Industry Tap and then walk home. I sit down and try to rattle off as much of this diary as I can in one hour. Then I cook an asparagus risotto. Afterwards we watch After Hours (dir. Martin Scorsese, 1985), which is a feel-bad yuppie nightmare film about a man having a very unpleasant evening in New York. It’s really good, in many ways a very uncharacteristic Scorsese picture, a mixture of noir, screwball comedy, psychosexual thriller and existential horror film. There are clear homages to Hitchcock’s style throughout and there’s also a really excellent moment that cites Kafka’s Before the Law, recast as a struggle to gain admittance to a nightclub playing Bad Brains. I read in Scorsese on Scorsese that the both the ending of After Hours, in which our bedraggled hero just ends up back at work the next morning, and the Kafka allusions were ideas that came directly from Michael Powell’s response to a preview screening at which the ending was fudged and unclear, and that Powell’s account of Kafka’s work really resonated with Scorsese because he had recently had a frustrating bureaucratic experience trying to get funding for The Last Temptation of Christ. Which is exactly the kind of coincidental and relatively meaningless trivia that I love. There’s also a great moment where the protagonist spends a while looking at some graffiti on a bathroom wall of a shark biting a man’s erection. It’s a film about emasculation and sexual neuroses, but it’s also a film about the intense lengths someone might go to in the hopes of encountering some kind of spontaneity and novelty in their drab life. Really one of the great New York films in the interplay we see between the unending potential of the city and the almost inevitable frustration and disappointment that results in the majority of the encounters we watch. It also feels a bit like a cocaine-addled downtown remake of The Exterminating Angel, another film about members of the bourgeoisie who just can’t quite make it home. It’s a fun watch; at times it feels as though it’s running the risk of getting bogged down and a little tiresome, but it has enough jubilant variety that it stays interesting and strange, equal parts hilarious and infuriating. Griffin Dunne, who I don’t really recognise from anything else, is a surprisingly good lead, perfect for an increasingly sweaty and abject man at the end of his tether. It’s the kind of film that makes you want to drink a regrettable cup of terrible filter coffee at 2am, or, at least for me, is the kind of film that — despite the horrible time everyone seems to be having — makes me wish I lived somewhere with multiple all-night venues and an atmosphere of there being an endless possibility for new forms of suffering available to nocturnal wanderers. I don’t really know why I haven’t seen this before; in many ways it’s an outlier in the Scorsese back catalogue, but a genuine miserable pleasure regardless.

Thanks for reading the film diary! If you enjoy reading the film diary, please consider financially supporting me, either through subscriptions, or through commissions, or just buying me a coffee. Please feel free get in touch if you have any thoughts or comments.

How do we negotiate the photographing of images that contain the body? What experiential, political or aesthetic contingencies do we bring to both the making and viewing of a cinema that contains the human form? If a body is different from our own—in terms of gender, skin color, or age—do we frame it differently? As a juror at the 58th Ann Arbor Film Festival, New York filmmaker Lynne Sachs will guide her audience through her own evolution as a filmmaker by sharing excerpts from her films, from 1987 to the present. She will explore the fraught and bewildering challenge of looking at the human form from behind the lens.

With selections from:

Drawn and Quartered (4min) San Francisco, CA | 1986 | 4 | 16mm

Sermons and Sacred Pictures: the Life and Work of Reverend L.O. Taylor (29min) Memphis, TN | 1989 | 29 | 16mm

The House of Science: a Museum of False Facts (30min) Tampa, FL/San Francisco, CA | 1991 | 30 | 16mm

A Biography of Lilith (35min) San Francisco, CA | 1997 | 35 | 16mm

Window Work (9min) Owego, NY | 2000 | 9 | video

Wind in Our Hair (Con Viento en el Pelo) (40min) Buenos Aires, Argentina | 2010 | 40 | 16mm and Super 8mm on video

Same Stream Twice (4min) Baltimore, MD/New York, NY | 2012 | 4 | 16mm

Your Day is My Night (64min) New York, NY | 2013 | 64 | HD video and live performance

And Then We Marched (3min) Washington, D.C. | 2017 | 3 | Super 8

A Year in Notes and Numbers (4min) New York, NY | 2017 | 4 | digital

Carolee, Barbara & Gunvor (8min) New Paltz, NY/ New York, NY/Kristinehamn, Sweden | 2018 | 8 | Super 8 and 16mm film to digital

The Washing Society (44min) New York, NY | 2018 | 44 | digital

Presented at:

• 58th Ann Arbor Film Festival – LIVE STREAM

https://prod3.agileticketing.net/websales/pages/info.aspx?evtinfo=671409~316d2c96-7be3-4c1b-82b1-d1a7143bdb35&epguid=38f27635-3533-4a5d-9ef7-ff186e949dd5&

• Punto de Vista Film Festival 2020 (Spain) – Cancelled due to COVID-19

http://www.puntodevistafestival.com/en/ultima_edicion.asp?Urtea=&IdSeccion=122&IdContenido=492

• Mana Contemporary (Jersey City, NJ) – Postponed due to COVID-19

https://www.manacontemporary.com/event/my-body-your-body-our-bodies-somatic-cinema-at-home-and-in-the-world/

• Shapeshifters Cinema (Oakland, CA)

See images from the film here: