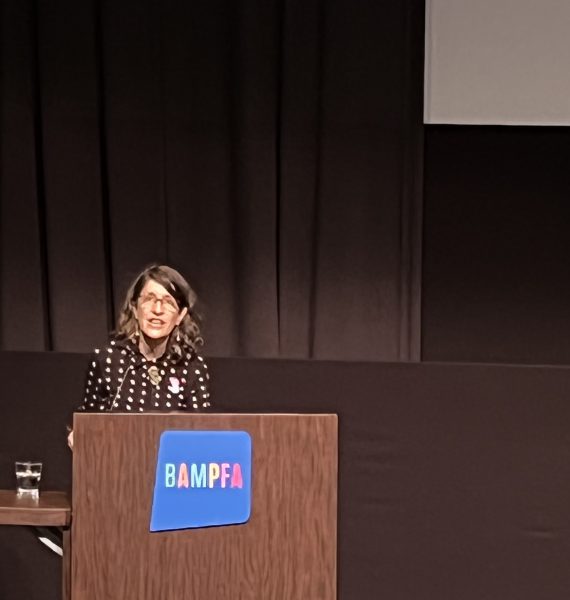

My I.O.U to the Real

2022 Les Blank Lecture

Berkeley Art Museum/ Pacific Film Archive

April 6, 2022

When Pacific Film Archive curator Kathy Geritz invited me to give the 2022 Les Blank Lecture, all of my experiences, challenges, obstacles and revelations regarding what constitutes the real came tumbling into my mind. I immediately confronted and embraced the life I’ve lead in the cosmos of the cinema, and more specifically my I.O.U, my gratitude, to that real for simply providing me with so much to think about and so much to record with my camera.

Tonight, I will share with you a selection of observations I have made in the course of creating approximately 50 films, installations, live performances and web art projects. Whether a 90 second ciné poem or an 83 minute feature, I learned early-on that my process of making films must push me to engage directly with the people with whom I’m working in a fluid and attentive way. I’ve never been truly comfortable with the term “director” or the hierarchical configuration of a movie set. I am a filmmaker who looks for other committed artists who are willing to collaborate with me in an adventure. These inventive souls are not my crew. We talk. We listen to each other. I pay them for their time and expertise. And then we set off on a journey.

Of course there are the people in front of the camera, what many documentary makers refer to as their subjects. In narrative film, these are the actors or, thinking in the aggregate, the cast. Again I find both of these monolithic terms anathema, an insult to their human presence. From my very first 16mm film “Still Life with Women and Four Objects” made in 1986, I asked the woman, the star in the film, to extract herself from “the objects” in order to shake things up for me. I wanted her to shift away from simply being a living, breathing prop. I invited her to bring something from her home that meant a great deal to her to our first day of shooting. She delivered a framed black-and-white photograph of early 20th century feminist-anarchist Emma Goldman. At the time, I had no idea who Emma was. I quickly learned. I, and with my four minute film, were forever changed. I’d claim for the better. I’ve been listening and learning from all the people involved in my films ever since.

This leads me to another perhaps more intricate form of entangling myself in the creative process. Between 2011 and 2013, I worked with seven Chinese immigrants between the ages of 55 and 80 living in the so-called “Chinatown” areas of NYC. Together, we made “Your Day Is My Night”, a hybrid documentary on their immigration experience and their lives in the place each of them calls home. Hybrid is the keyword here, for it was my interaction with these participants that sparked me to find a completely new approach to my documentary practice. I started this project with the intention of discovering more about these people’s lives through a series of one-on-one audio interviews. Then, I turned each of these conversations into a monologue that I gave back to each person so that they could perform their own lives by both memorizing their lines and also improvising, all in a dramatic context that gave them the freedom to express themselves, and a release from the intimidation and vulnerability of not knowing what would happen next. According to the seven people in my film, this in turn gave them the liberty to play with their spoken words with whim and impetuousness, not to feel indebted to the limitations of their own historic realities. At my performers’ insistence, we ultimately moved the hybrid nature of the piece one step further. As a group, they pushed me to search for a story beyond their lives. They wanted me to make their job of articulating their experiences more interesting so I brought in one “wild card”, a Puerto Rican woman actor who would move into their shared, filmic apartment. Her arrival transformed the piece into a story that embraced each person’s immigration experience without being confined by it.

Over a two year period, we took our live performance with film to homeless shelters, museums, universities and small theaters throughout New York City. I then turned our collective work into a film. From this experience, I learned that even a more conventionally narrative film is simply a documentation of a group of people making something together. My integration of a traditional observational mode with a more theatrical engagement gave me the chance to reflect on the work I had done over 25 years earlier, as the sound recordist on Trinh T. Minh-ha’s “Surname Viet Given Name Nam”. This film also challenges monolithic notions of documentary truth. Some of you saw it in this very room when Minh-ha gave the 5th Annual Les Blank lecture.

I also wanted to share something about the exhibition of “Your Day is My Night” which adds another layer to our conversation around collaboration both within the film’s production structure and its exhibition. The first evening that we presented this piece to an actual audience, there was a rather typical post-screening Q and A. There I stood with all of the participants in the film. When members of the audience asked these seven Chinese immigrants to the US how they felt about working on this rather experimental film, they all became quiet, then they whispered together and a few minutes later, one spokesperson came forward to say simply “We do what Lynne tells us to do.” There was a hush in the room. No one knew what to say. Honestly, I felt embarrassed, at a loss for what to do. I put my microphone down, walked over to the group and explained that in the US it was okay for them to say whatever they wanted publicly, to express their feelings about their experiences without any punitive repercussions. At the next screening, they each energetically took the mic from me. With the help of a translator, they articulated their own interpretation of our shared creative process. Never before had they had the opportunity to talk so freely in public, in China or in the US.

The performers in “The Washing Society” which you will see tonight gave me another kind of gift in terms of their response to and expansion of my creative practice. In 2014 and ’15, playwright Lizzie Olesker and I traipsed around New York City trying to record interviews with laundry workers. Most of them were recent immigrants who did not yet speak English or have their legal documents for living in the United States. Neither their bosses nor their husbands wanted them to talk to us. Thus, they refused to be on camera. So the two us confronted this “production obstacle” head-on. We conducted a series of informal non-recorded interviews and then we wrote a play that used the stories we’d heard as source material for a live performance and film. We called it “Every Fold Matters”. We worked for over a year with four professional actors and dancers who were open to devising a strategy for making a site specific piece that would be performed in actual laundromats around the city. In the process, we borrowed from reality in order to create a new hybrid reality.

Veraalba, one of our performers, was formally trained as a dancer but also deeply influenced by the radical choreographic gestures of feminist thinker and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer. Through her physical investigations of folding laundry, the piece gained an exhilarating gestural vocabulary that gave our show and then our film its rhythm and its musicality.

Jasmine, an actor in the film with traditional theater experience, embraced our whole, inclusive process so profoundly that she transformed herself from an eager, responsive actor into a generative contributor. One day during our rehearsals, she texted me with the words “I’ve been living with my grandmother Lulabelle all of my life but she never told me she had worked in a laundry from 1968 to 1998 until I started working with you all on this show.” A few days later, we were filming with Jasmine and her grandmother while she conducted the first documentary interview of her life. She asked her grandmother about her collective actions for better wages and working conditions. The openness of our process gave her the chance to find out more about the woman with whom she’d lived all her life. In addition, this intimate cross-generational exchange between two women in a family gave a new layer to our film.

Now, I would like to take you on a journey through my aesthetic, material trajectory as an experimental documentary filmmaker. I need the word experimental here because it commits me to pursuing formal investigations of the medium. This is the only way that cinema can continually tackle, confront, even tickle my curiosity about the world. What is particular to me about cinema is its embrace of sound with, alongside, underneath and beyond image. In the late 1980s, I made my first longer format documentary “Sermons and Sacred Pictures”, a 30 minute portrait of Reverend L. O. Taylor, a Black Baptist minister who also shot 16mm film and collected sound recordings. At a certain point in the film, audiences are in total darkness while they hear the chatter of church congregants at a baptism in a river. At the time, this film was rejected for TV broadcast because the station producer assumed viewers would give up and turn off their televisions. Tonight I think about this film I made in my late 20s with a new perspective. I think at this moment about what theorist and poet Fred Moten calls “hesitant sociology”, and about the ways that we can integrate a propensity for abstraction into an endeavor to bring attention to a subject that might not have received its rightful place in history. Where do education and exposition end and aesthetic rigor begin? Do we necessarily lose the impact of the former when we give light to the later?

In “Which Way is East”, a diary film made in Vietnam in 1994, I begin with a series of richly colored Kodachrome brushstrokes juxtaposed with my own voice-over remembering what it was like to watch televised images of the war in the late 1960s. As a six year old child, I would lie on the living room couch with my head hanging upside down watching the screen, inverting the images, unintentionally abstracting them somehow. At that age, I just barely understood the dismal war statistics I was hearing. Within my film, I decided to make this oblique reference to the archival images of the Vietnam War rather than delivering actual illustrations from the time period. That was enough. I expected my audience to work hard to fill in this absence, a pointer to the horrifying collateral damage of the US involvement in Vietnam. Each viewer has to reckon with their own relationship to this history, as full or empty as it might be. At the time, I was cognizant of Belgian filmmaker Claude Lanzmann’s refusal to provide a visual proof in the form of archival footage from the concentration camps in his 1985 “Shoah”, an episodic series on the Holocaust. At that time in history, forty years after the end of World War II, he felt that that haunting power of those images would be even more searing if his audience had to rely on their internal repository. Just in the last year, I had the chance to read historian and theorist Tina M. Campt’s new book Listening to Images in which she prompts readers to look at archival footage in a way that forces us to hear what was never recorded, to bring our imaginations into the synthesis and recognition of a partial history that needs, at long last, a place in our communal consciousness. The lacunas are mended by my, your and our active modes of participation. Both Lanzmann and I resisted the inclusion of images of horror, cautious about our own complicity by including them, assuming their implicit power that comes from absence.

Two weeks ago, I went to Berlin to shoot for a new film I am making called “Every Contact Leaves a Trace”. I spent several days talking with an 80-year old German woman about many things, including the moment when she first became aware of the concentration camp atrocities that had been committed by the Nazis, the everyday men and women who lived in her own town. She had the chance to watch archival footage of systematic killings and so much more in Alan Resnais’ 1956 documentary “Night and Fog”. It all became absolutely clear. Here was the proof. When I heard this woman speak of the potency of these images, I immediately asked myself if I had failed in my own work. I’d assumed the existence of an internal archive of the horrors of the Vietnam War. In fact, it might not have been there, at least to a younger audience. Had I failed in my own obligation to manifest a history that needed examination?

In addition to a deep involvement from my compatriots in front of and behind the camera, I have come to expect a parallel engagement with my audience. In order for a multi-layered cinematic experience to happen, there must be a “synaptic” event that transpires. Only through this internal occurrence can we register meaning. My awareness of the aperture inside the camera convinces me that we must find intimacy with light to accomplish this kind of charged flow from screen to eye. I have had the same Bolex 16mm camera since 1987. I know her well and feel as if she knows me.

As we sit here together in this room, I would like to share with you just five images from my entire career as a filmmaker. They are part of my IOU to light, the only continuous collaborator who has remained with me for all of these years.

This is an image from “Still Life with Woman and Four Objects” (1986) a film falls somewhere between a painting and a prose poem. It’s a look at a woman’s daily routines and thoughts, interweaving history and fiction. This is the film I mentioned earlier with the framed photo of Emma Goldman.

In this image of an avocado pit just peeled and prepared for growth, you see a slant of sunshine coming through a skylight in the ceiling. This is the first time that I truly learned how to transform – via an awareness of aperture and f-stops – what the eye sees into something only the camera can witness.

In “Window Work” (2001) a woman drinks tea, washes a window, reads the paper– simple tasks that somehow suggest a kind of quiet mystery. I am the performer!

Here, my hermitic, domestic space is ruptured by a backlit newspaper. It glows. As cinematographer and performer, I discover how to sculpt light through silhouette.

In, “Your Day is My Night” (2013) immigrant residents of a “shift-bed” apartment in the heart of New York City’s Chinatown share their stories of personal and political upheaval.

Here light transforms Mr. Tsui’s profile into a gently sloping landscape. He fills the frame completely and in the process conveys awareness and presence.

Over a period of 35 years between 1984 and 2019, I shot 8 and 16mm film, videotape and digital images of my dad. “Film About a Father Who” (2020) is my attempt to understand the web that connects a child to her parent and a sister to her siblings. Here, my father has photographed three of my siblings playing in the water in the early ‘90s.

This time worn image reveals my dad’s point of view. There is no detail. Only light and color affirm a quality of compassion and observation, simply through the texture.

This is one of the last shots from “Film About a Father Who”. It’s clearly a degraded piece of old video, having lost all of its color and detail. And yet, in its starkness, this high contrast black and white image evokes a pathos. After spending 74 minutes with me in the film, viewers are able to fill in what is missing.

In each of these light-sculpted images, I explore the concept of distillation which has always been at the foundation of my work. I am an experimental filmmaker and a poet. Thus I am far more interested in the associative relationship between two things, two shots or two words than I am in their cause and effect, or their narrative symbiosis. For me, a distillation is a container for ideas and energy, a concise manifestation of a multi-valent presence that does not depend on exposition. A distillation is not a metaphor; it’s more like metonymy and synecdoche, where a part stands in for a whole, and is just enough.

I once asked a student of mine why she wanted to make documentary films. She told me that she wanted to make gifts. Just that single word helped me to better understand the ways that this kind of practice can embrace so much about life. Working with and beside reality allows us to feel relevant but also gives us the chance to share something we love with others. Through his engaged, compassionate, ingenious approach to filmmaking, Les Blank gave us approximately 50 gifts. His vision of music, food, culture, and humanity came through every frame of film.

I too have made about 50 films, web art projects, performances and installations. Like Les, each endeavor reveals my curiosity and awe for the world around me, my I.O.U to the Real.