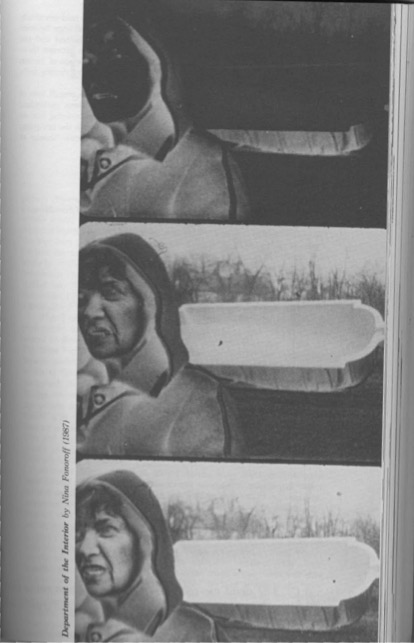

Department of the Interior

Lynne Sachs, Cinematograph Journal of Film and Media Art, 1988

“There is a shadow cast across Nina Fonoroff’s Department of the Interior. It is the shadow of the Founding Fathers, those luminous figures to whom we give credit for creating our laws, our language and our rational mode of thinking. Much to their possible chagrin, however, this office of the Executive Branch (which is given the responsibility of maintaining public land) is no longer completely intact. Instead, the irrationality of the Mother and the child has begun to take control.

Whether a relic of the state or the family, Fonoroff’s white wood panel suburban house leaves us with no more than a skeleton of a way of life.Through the apparatus of the camera lens, this sign of stability, propriety and happiness is read but never understood, visited but never entered. Time after time, I-as-a-spectator-am-brought-to-the-front-door-of-this-house. Yet I am excluded (as a woman?)from the very place I was told was mine to shape and to manage.I am left outside with my memories and my dreams.

•••

The hysteric, whose body is transformed into a theater for forgotten scenes, relives the past, bearing witness to a lost childhood that survives in suffering. (from The Newly Born Woman by Helen Cixous and Catherine Clement)

The various codes contained within the film tell us how to read practically every element involved in its construction as a text. The exchange between the music (Gian Carlo Minotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors) and the domestic banging around, for example, establishes a tension between those sounds created by culture and those that are natural expressions of human unrest. Eventually, the opera is destroyed – cut to pieces by ringing bells, furniture thrown to the floor, knocking.

There is a compelling, almost consuming quality to the overall tone of Department of the Interior. Perhaps it is the enigma of these particulars. Fonoroff deposits a curious array of clues into the floating, evolving box we call a film. Then we (as spectators or researchers) are left with the intriguing task of compiling these facts and creating a narrative, our own “theater of forgotten scenes’.’

Lynne Sachs is a filmmaker living in San Francisco. She is currently working on an experimental documentary based on the life of a minister from Memphis, Tennessee who made his own films in the 1930s and ’40s.”