By Jonathan Marlow

January 7, 2026

https://www.hammertonail.com/interviews/lynne-sachs/

Some filmmakers are known for their documentary works. Others for their narrative films. Still others—the better filmmakers (for me), generally—do not fit comfortably into either category. Or any category whatsoever.

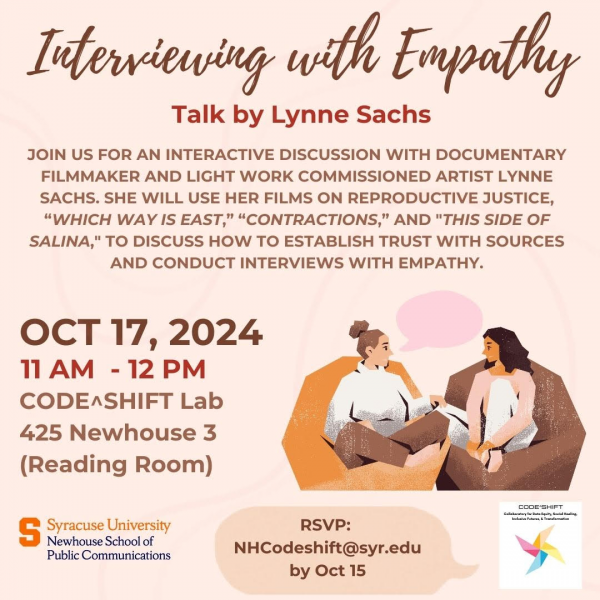

Poet / artist / filmmaker Lynne Sachs is one of the later. During a brief tour of Northern California for a variety of events (partially illustrated below), Jonathan Marlow, SV Archive [Scarecrow Video] Executive Director, took an opportunity to meet at a small café in the East Bay (recommended by former Pacific Film Archive programmer Kathy Geritz and former Views from the Avant-Garde programmer Mark McElhatten, a short stroll from their home).

[Individuals referenced (in order-of-appearance): Lynne Sachs. Jonathan Marlow. Kathy Geritz. Mark McElhatten. Kathleen Quillian. Gilbert Guerrero. Betty Leacraft. Meryl Streep. Bradley Eros. Robert Beck. Brian Frye. Jeanne Liotta. Mark Street. Dan Rowan. Dick Martin. Hansel. Gretel. Jerome Fandor. Fernando Pessoa. Ira Sachs. Peter Hujar. Bette Davis. Dana Sachs. Marguerite Duras. Chantal Akerman. Louis Massiah. Angela Haardt. Heinrich Heine. Walter Benjamin. Lawrence Brose. Oscar Wilde. Matt Wolf. Paul Reubens. G. Anthony Svatek. Maya Street-Sachs. Noa Street-Sachs. Boris Torres. Kirsten Johnson. Viva. Felix. Rae Wright. Lori Felker. Werner Herzog. Heddy Honigmann. Adam Curtis. Stephen Vitiello. Emily Packer. Ana Siqueira. Claire Lasolle. Gunvor Nelson. Carolee Schneemann. Barbara Hammer. Dorothy Wiley. Robert Nelson. William Wiley. Lonzie Odie Taylor.]

[conversation already in progress in Oakland, California, 2025 November]

Hammer to Nail: Do go on about Shapeshifters, a very wonderful place! A very wonderful family enterprise.

Lynne Sachs: It is also a really good place for a performance (which is basically what Kathleen [Quillian]* and I were doing). She even was in costume! The whole conceit was built around lint. I’ve done a few book readings like this, always tailored to the space. This was probably the eighth. I discovered that she was into lint. I love the idea of lint because it comes from the hair on our bodies, little bits of skin, some fabric. She collects it because she is a sewist.

*[ed. Proprietor of Shapeshifters with Gilbert Guerrero, a remarkable microcinema / microbrewery in Oakland.]

HTN: You both have that in common. At the conclusion of EVERY CONTACT LEAVES A TRACE, you’re in the midst of needlework renderings of your drawings. There must be a show at some point of those pieces?

LS: I didn’t really go very far with the sewing. As a kind of trope or a connection—when we’re pulling the thread out—it creates a tactile trajectory, from her back to me and me back to her. But Betty [Leacraft, in the film and in life]…

HTN: …she is a captivating character!

LS: She is. She is a force of nature! She really, really, really wanted to come to Amsterdam [for the premiere of EVERY CONTACT LEAVES A TRACE at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam/IDFA]. It would be difficult for her to get around there. Whenever I find out where the U.S. premiere will be, she’ll be there for that.

HTN: What is evident—from not just this film but all of your work—is that you’re very interested in making the seams of filmmaking fairly apparent. In this instance, you’re directing her actions (and those direction remain in the documentary). “You need to put your hand in the frame.” She was resisting every part of it.

LS: She even says, “I’m not Meryl Streep!” Streep is mentioned twice in the film. When she says her name, that actually led me to think about all of the different things that a documentary expects of a subject. To be as charismatic as an actor. Performing as a character. There is a paradigm in documentary—which I don’t follow at all, really—that says you have to build your narrative. That is not a word I use often. You build [a narrative] around a character people can identify with or people feel appalled by.

HTN: That goes back to a whole formula of literature. I love literature but I don’t believe that literature needs to impose itself on us or our work. You definitely hold elements of literature throughout your films. The written word comes through consistently [and, occasionally, literally]. Not traditional storytelling, with a notion of a conflict and then a resolution. There is prose and then there is poetry. Poetry seems to be a stronger influence in your work.

LS: Totally. Yes.

HTN: Clearly, within the structure of EVERY CONTACT LEAVES A TRACE, you introduce a whole array of possibilities and then you narrow those possibilities. I have to admit, if I could ever be as effortlessly charming as Bradley Eros [another interviewee in the film], I would aspire to be that sort of person.

LS: I am so happy you said that. Absolutely.

HTN: Anytime I go to Anthology [Film Archives], he is there. He is a welcoming presence.

LS: Does he take your ticket?

HTN: The last time that I was there, he did! He was there. Jeanne Liotta was there that evening as well. A pleasant surprise.

LS: The thing about Bradley is that he breaks the mold! The idea that a [business] card is a distillation of who you are… A card doesn’t epitomize “who you are” but it is “how you want to present yourself.” Everything is represented. The way that you dress. The way that you act. It is all a performance of some sort.

HTN: The card is the piece that you take away. Everything leaving a trace, part of you is still there within the card. The process of handing the card to someone else, you’re basically giving a piece of yourself to that person.

LS: Exactly. I get that energy when I hold a card. It brings all that back. I remember this person. I believe they work as mnemonic devices. The thing about Bradley, I’d said, “I’d like to talk to you about this film.” The way that these pieces of paper can become the essence of a person. I didn’t even know if he had a card! I just thought he might have some ideas around them. I get to his house and he has a lifetime of cards from other people. Then he disrupts them in collages. He shoots holes through them. He becomes them! He breaks up everything about the model of a card. That was exciting to me. It was far beyond what I would’ve expected.

HTN: We initially met at the Robert Beck Memorial Cinema [which wasn’t a cinema but a series at Collective Unconscious], along with his then co-conspirator / co-host / co-programmer Brian Frye. I could certainly relate to their impulse to exhibit otherwise nearly-impossible-to-see work and share that work with other people.

[ed. Both Sachs and Marlow are on the Board of the Canyon Cinema Foundation with Frye.]

LS: I didn’t even live in New York at that time. We [Sachs and filmmaker Mark Street, one of the cinematographers on EVERY CONTACT LEAVES A TRACE] lived in Baltimore. We would come up and go to the Robert Beck Memorial Cinema. It was like going to see [Dan] Rowan and [Dick] Martin.

HTN: Eros and Frye, in their introductions, were opposites.

LS: One was very tall, the other not. They were kind of foils for each other in a way. They were sweetly glib and charming.

HTN: It wasn’t an affectation. They weren’t trying to be different. They just were different. Similar things were happening in San Francisco and Brooklyn and Vancouver and Seattle and Chicago and elsewhere with ambitious individuals creating nontraditional spaces to screen work. I’ve exhibited films in all of those cities (and others), as have you. This way of talking about time and space(s) has much to do with your documentary.

LS: You don’t know that you’re in an era until it is actually ends.

HTN: You hardly know that it was even a phase of your life.

LS: A turning point. A chapter, until you can finally look back at it. The cards gave me that chance to think about the passages of time in which I was doing something consistently. Or maybe a period of time in which health issues were overwhelming. Or another period of time where I was traveling a lot or when I had young children. The cards are like little punctuation marks for all of that. The thing is that they are only punctuation marks for the most part. They’re not whole personal epochs. They’re little moments in time. People talk about Hansel and Gretel and their little crumbs. The thing is that I didn’t leave them behind. I brought them with me.

HTN: I should admit at this point that I was very nervous watching the film because I knew that I was included in those stacks of cards. I have given you various cards over the years—for Fandor and San Francisco Cinematheque, in particular—at some point. The moments that were particularly enlightening for me was seeing assorted cards in there for individuals whom I know or once knew. That brought up extension within the film and memories of folks I haven’t thought about in quite a while.

LS: I am glad that happened to you because I’m really intrigued by a film that can do that. Films that take you to another space. It takes you along my trajectory but, in the end, you walk out thinking about your own.

HTN: Not everyone wants that from a film. Although I don’t know how else you would move beyond a project that is theoretically about one person to a film that is ultimately about all people.

LS: Characters could have various different personas and identities. It reminds me of The Book of Disquiet where Fernando Pessoa says, “Everything that surrounds us is part of us.” That was very meaningful to me.

HTN: To me as well.

LS: Both experientially and, in this case, what it is to have a shared consciousness with another person, even in a fleeting way. That was very important for me to understand.

HTN: Why do you think it is? I had felt it was a strange synchronicity that your brother [Ira Sachs] was visiting the Bay Area at the same time.

LS: Actually, he is not here. He was supposed to be here yesterday.

HTN: At the Roxie screening [of PETER HUJAR’S DAY].

LS: I think he did the discussion on Zoom because of COVID. He was here spiritually even though he should’ve been here in body. We didn’t know of the overlap until [mutual friend] Kathy Geritz told us!

HTN: Two different threads! Simultaneously. Why do you think it is that you and your brother both became filmmakers?

LS: I will tell you that I’m the older one, by four years. When we were growing up, we didn’t both think, “I want to be a filmmaker!” Definitely not the term “filmmaker” or even to make movies. He was really involved in the theater world. He was also the kind of kid who watched Bette Davis movies and things like that. I was a kid who liked to write poetry and I did that for years. I was probably more into photography and drawing and things like that.

HTN: You’re both very artistic. That doesn’t come from your parents, necessarily.

LS: Definitely not. Not at all. My mother said that she gave us a pretty nice box of crayons.

HTN: There is a sister in-between.

LS: Dana [Sachs]. She is a writer. We’re all drawn to the arts! We are. Our parents were not. My mother would say, “Well, I would take the kids to museums!” She wasn’t obsessive about that. I love art history and I can talk a lot about different artistic periods. When I took art history classes, people were memorizing dates and looking at slides. I thought that was oppressive. I think Ira probably feels the same way. But we drank it up.

HTN: Were you exhibiting your photographs before you started making films? Or was this happening in parallel?

LS: I was very involved with painting. In college, I did a lot of painting and then I was in the more academic world. Then I went to live in France for my junior year abroad. I saw a few films by Marguerite Duras and [Chantal] Akerman. It was a total switch! I found that you could bring in photography, you could work with people, you could write poems and they can all go in the same vessel. That was incomprehensible to me before that.

HTN: What did you see, specifically?

LS: GOLDEN EIGHTIES!

HTN: Appropriate.

LS: I never finished with the Streep story! She is mentioned in two places. There is the one with [shape-shifter of textiles] Betty Leacraft. Louis Massiah asked me to teach a class on film and performance in Philadelphia. Only two people took it and she was one of them! I got to know her. It was meant to be. Years later, I wanted to find her. I actually had to hire a kind of make-believe detective that Louis helped me find because none of the phone numbers or emails on her card worked. You know, when you’re in this field, the more obstacles that come your way, the more that you say, “I’m meant to do this.” Because I make hybrid films, if I didn’t find her, I was going to invent her! Then I did find her with the help of the faux-detective. I went down to Philadelphia to talk to her about the first time that we’d met and about this notion of teachers and students. Yet I felt I’d learned more from her than she had learned from me.

HTN: The framing is fairly tight on her.

LS: We’re sitting there together and I said, “Could you use your hands this way?” The way you might direct an actor. Then she says, “I’m not Meryl Streep!”

HTN: You’re asking her to do things that probably felt unnatural for her.

LS: She said, “I’m not going to be anybody but myself.” She invokes Meryl Streep because she is the epitome of someone who can transform herself. But she comes up again in the film in a totally different place. There is a woman in the film named Angela Haardt. You might know her.

HTN: She used to run [Internationalen Kurzfilmtage] Oberhausen. When her voice is first heard in the film, I thought, “I know this voice!” She is a wonderful person.

LS: She is a really, really, really special person. They all are! Angela and I talk about the Holocaust. She was a child during the Holocaust in Germany and we talked about the fact that she didn’t really understand what was happening around her when she was growing up. I’m using the word “Holocaust” here but—when I was growing up—we didn’t use the word. We talked about World War II and we talked about concentration camps. But there wasn’t one word that invoked everything. I was wondering why that word came to me later in life—as a teenager—but my parents and grandparents were not using that word. Where did it come from? I did some research and there was a television miniseries called THE HOLOCAUST and Meryl Streep was the star! The series popularized it. Then it became the Shoah.

HTN: This goes back to what you were saying before about the notion that the era you’re in gets defined later.

LS: That is exactly right. Exactly. One way to think of it is in terms of copyright. We wait for the copyright to lapse in order to reinterpret work. In poetry, that idea that something can’t be touched until some period after it has been in the world for a while [doesn’t really exist]. We can engage with it now. It is what was happening with Heinrich Heine and other poets of that era. Folks were immediately inspired to take these ideas and adapt them and use them in different ways. Angela Haardt reads THE SILESIAN WEAVERS [in the film, about the Weavers’ Revolt in 1844, the same year that the poem was written].

Angela is a very erudite person. A person who knows about cinema and many, many more things. She is someone who enlarges my worldview. That is one of the reasons that we enjoy reading and meeting new people. They make you think about things in new ways. The next afternoon, after we filmed, I am on the subway underneath Berlin and I am going with her through Heinrich-Heine-Platz. Seeing it with an audience [in Amsterdam], I will be very interested to see their reaction to this section about the Holocaust. Like Walter Benjamin’s idea of the “angel of history” where you’re moving forward but you’re always looking back. I am thinking about Gaza and my own culpability. What is it to be a Jewish person today? All those things went through my mind [during this scene].

HTN: You decided to include an individual where you’re conflicted about things you have discovered about them. Those decisions are part of the running narration of the film, to decide whether to remove their story and potentially leave them and their story on the cutting-room floor.

LS: If I decided to remove them, then why am I even doing this? Whether it is misinformation, am I then not allowing this person to speak for themselves? If I’d engaged in removing it, I’d be preventing them from telling their side of a story. A story that other people are using anecdotally or for whatever ends they might have.

HTN: In the context of your references to the Holocaust, some who died in the concentration camps are often excluded from the conversation.

LS: That is my own personal connection to what is happening in Gaza. These are the ways in which a huge Palestinian population within Israel are not included in this larger dialogue.

HTN: It is a very good question and there is a less-than-good answer for it. It is all terrible. Disproportionately terrible. Terrible in proportions difficult to fully comprehend.

LS: One of the things that I came to terms within this film is that when you’re working with reality—or you’re working in a documentary practice—sometimes things become difficult. They’re difficult logistically or they’re difficult emotionally. You’re traumatized by something and you say, “You know what? I’m just going to take that part out because I haven’t resolved that.” There is a man—Lawrence Brose—in the film who had been through an extremely traumatic legal case involving Homeland Security, accusing him of possessing child pornography. I had his card from thirty years earlier.

HTN: When you initially reached-out to Lawrence, were you fully aware of the case?

LS: I reached out to him because of this. I reached out to him because I couldn’t resolve how I felt. We make these conclusions based on impressions or facts. We also realize that the facts we thought we’d collected might be misinformed. Did he have child pornography or not? Why was it that his legal situation catapulted him into the public arena? Many people knew about the case. I had friends who said, “Well, he didn’t make the pornography.” Others immediately avoided him over these accusations. Then other people said he was accused of something that he didn’t even do at all. I kept wondering if it was my job as an acquaintance of his to resolve that. I decided that the harder it was for me to understand his life, the more I had to insist to include him in this film. I reached out to him during the early days of the pandemic and we did a series of Zoom conversations. Interviews for hours and hours, over several years.

HTN: Was it his choice initially to be in silhouette?

LS: I wanted to give him that option. Then he could just talk [without concern]. I said, “We’ll just use the audio.” He wasn’t sure whether he wanted to be visible. The more that I talked to him, the more I realized that he had been a victim of a state system that that was targeting people who were different. People who were gay. People who were artists. Then he also explained that it wasn’t even material he had downloaded. Nevertheless, I still was bewildered by my own ambivalence.

Then he started to articulate the parallels between his life and the life of Oscar Wilde. He had been targeted by the system and sent to prison. It essentially destroyed him. In Larry’s case, he was sent to Attica. He was punished for who he was rather than what he had [supposedly] done. We worked together on getting the story correct. Then, about eight months ago, I called him and I said, “I’ve finished the film. I’d love for you to see it before I show it anywhere.” He said, “You better bring it soon because I am going to die in a month.”

HTN: I noticed that acknowledgement at the end of the film.

LS: That was on a Friday. On Sunday, I flew to Buffalo and I showed him the film and he gave me his blessing, which was relief. We both had a cathartic moment. It was very profound to talk to him about the film. He was the first person to see it completed! He did die a month later.

HTN: Have you seen the documentary by Matt Wolf about Paul Reubens?

LS: Not yet.

HTN: A section of the film deals with similar issues of being railroaded for having child pornography. In his case, these were primarily artworks that he had purchased. The authorities came in and accused him of having naked photographs of young boys. They confiscated it all. Granted, this is a bit of an oversimplification.

LS: With Lawrence Brose, he knew how media works and the hierarchies of a filmmaker and their subject. He was constantly apologizing to me. He was saying, “Did you get what you want?” Whereas Betty Leacraft had a clear idea about who she is [and how she should appear in the film]. If you are going to be photographing her, she needs to define the terms. Different forms. Different grammars.

HTN: How do you feel about being a subject? Because you are often a parallel subject within your own film.

LS: You have more control over how you appear in your own work. It is interesting that you say that. I mean, I definitely grow older! There is an image of me in Germany in the late-1980s. The Berlin Wall is still up. Then there is an image of me in my sixties.

HTN: There was never any question that you would be the narrator? You were never concerned about distancing yourself from the telling?

LS: I could have. I could have distanced myself a little more by using the voice of someone else. I actually thought about writing in the third-person at times.

HTN: Or having your daughter(s) [Maya Street-Sachs and Noa Street-Sachs] as surrogate(s)?

LS: Maybe that’ll be my next film.

HTN: I was thinking more in terms of the ways in which you have a kind of “rogues gallery” of collaborators these days. Consistent individuals involved in the shooting and editing. You keep pulling a reliable group on individuals together to collaborate. Does that then make you recent films variations on a theme?

LS: You noticed, for example, G. Anthony Svatek.

HTN: Indeed.

LS: You know him very well.

HTN: I adore Anthony!

LS: Do you want to know what footage he shot? It is very beautiful. He shot the footage at the end with the thread, the sewing.

HTN: That sequence is remarkable. Truly beautiful. The ways in which you’ve inserted the drawings throughout and then how these drawings are animated. The crafting of those drawings with the needlework is astounding.

LS: Like trajectories. I called them vectors. I was reading about what you’d call affect theory. I wish something on you and you create an emotional response in me. All of those come from this whole conversation.

HTN: Every relationship is some form of compromise. Friendships, couplings. Ideally, those compromises are equal. Sometimes they’re greatly out of balance. I either open up to you or I build a wall.

LS: I feel punctured by you or I feel enthralled by you. I think about all of those things. I wanted to say that and many of those things at the same time. I think the stand-ins for me—at another point in my life—were my niece and nephew.

HTN: Who are in the film, like a Greek chorus. They’re very charming.

LS: Those are Ira’s kids. Ira and [painter / artist] Boris [Torres].

[…and cinematographer / filmmaker Kirsten Johnson]

HTN: I was wondering. I presumed that they were relations but I didn’t know how they were related!

LS: They grow-up in the film because we started when they were around eight. They’re twins [Viva and Felix] and they’re very perceptive. But they challenge me.

HTN: They keep asking you questions about the purpose of your work.

LS: They’re absolutely the Greek chorus! They’re just these kids sitting on a bed, asking, “Why are you doing this? What are you thinking about this?”

HTN: Wise beyond their years, seemingly.

LS: They’re also silly about these interactions. They come up with these ideas for the cards that I never would’ve imagined. “Why don’t you put them in a bottle and throw it out to the ocean?” Felix says, “Why don’t you put them on the wall of your house and then open it up?” That is basically what I did! He understands time. There were things that came to my mind from watching a lot of movies with Ira [as a kid]. Putting cards in a bottle and throwing them out to sea. The message in a bottle. The idea of a house containing your whole history. Or putting the cards in balloons and then letting them float away. Then they become someone else’s property.

HTN: They propose the ending. [spoiler] The box goes back on the shelf.

LS: Thank you for noticing.

HTN: There is an element of you on that shelf. You and an assortment of folks that you’ve met.

LS: I’ve told people about this film and many have said, “Oh, I used to have a box of cards, too, but I threw them all out.” They don’t take up a lot of space! But you’re actually throwing out these stories.

HTN: It is difficult for me to let go of them primarily because there are so many people who are now gone. Either physically gone or they’re merely not a part of my life anymore.

LS: It constantly brings you back to that moment [of meeting].

HTN: What was the dialogue with that person where they felt that they wanted to continue this conversation? “Please stay in touch.” Many of them I remember completely. I remember the circumstances of our meeting. Others, I do not recall at all. The actor playing the therapist addresses this directly. She persists in interpreting the limited information you’ve given her.

LS: She says these things but very quietly. You could miss it! I wouldn’t have taken [what she said] literally. We’re always acting on camera [and off]. We are.

HTN: Did you prompt her to ask these questions?

LS: I told her a little bit about what had happened in my life when a therapist or maybe a nurse—I’ve conflated these two together—had said to me, “If you want to have a baby, just make it happen.” I was literal about it and that is not what she [Rae Wright, the actor playing the therapist] thought about that. She and I had a series of conversations about it and she really moved into a very reflective, therapeutic mode while we were making the film. She challenged me in really tough ways. I didn’t expect her to do that.

HTN: I could see that you were unprepared with how to respond to these questions. Which is why it doesn’t seem like she is acting [and she isn’t identified as an actor until the end-credits]. You have seen Lori Felker’s PATIENT?

LS: I have seen it.

HTN: It operates in a similar space where you don’t recognize that the people you’re watching are actors.

LS: Exactly.

HTN: They’re not what they appear to be. Your relationship with what you’re seeing changes the moment you realize that what you’ve just seen is not what you believed you were seeing. When I saw that in the end-credits [of EVERY CONTACT LEAVES A TRACE], I’d re-thought through your conversations with her. It was clear on first-viewing that your reaction was genuine. You weren’t complying but she was performing. Those interactions were extremely interesting.

LS: It changed everything. I wanted to include it [at the end] because I did not want to ruin that experience for the viewers. I sorted through all of that while making this film. I have come to see every narrative film as a documentary. A documentary of a bunch of people getting together, playing make-believe. Unless it is Candid Camera, most documentaries are forms of performance. There is a certain kind of contrived intention to it. There is a bit of a theater-game going on. We were playing a theater-game but she [the actor playing the therapist] was considerably more clever than I was.

HTN: Well… She is a professional actor!

LS: True. Not every actor likes to improvise.

HTN: Also true.

LS: Many do not. She had been recommended to me by a friend. She took a lot of risks and we spent months and months working together. She really becomes a therapist for the surgery. She transformed from being an actor to being the actual thing!

HTN: For the premiere [at IDFA, mid-November], it seems as if audiences there are more accommodating of films which intersect at the margins of nonfiction and quasi-documentary. [Perhaps even venturing into the “ecstatic truth” realms of Werner Herzog, Heddy Honigmann, Adam Curtis and others.]

LS: I am excited for these screenings!

HTN: Will there be others associated with the film in-attendance?

LS: [Composer] Stephen Vitiello will be there as well as [editor] Emily Packer. She is coming with her mother! The three of us will be together [to speak about the film]. You know who else is going to be there? Someone we both know: Ana Siqueira [of the Belo Horizonte International Short Film Festival].

HTN: I am immensely fond of Ana and the work she has done in Brazil! I was introduced to Ana at the same festival where I met Claire Lasolle [of FID Marseille]. Claire is among the cards pictured in your film! Connections! One of the catalysts for your visit to the Bay Area is a screening at BAMPFA of the work of [Swedish filmmaker and San Francisco Art Institute teacher] Gunvor Nelson which [Program III] includes your short CAROLEE, BARBARA & GUNVOR, along with RED SHIFT, TIME BEING and BEFORE NEED REDRESSED, her collaboration with Dorothy Wiley. Have you ever seen BLEU SHUT, their film with Robert Nelson and William Wiley?

LS: That is one of Bob’s films I’ve never seen.

HTN: It is one of my favourite shorts of all time!

LS: I will try to find it. I will be introducing the program and I have this fantastic document that she created for her students called “Notes on Editing.” I’ll send it to you when I get back [to Brooklyn]!

HTN: What was she like as a teacher [at SFAI]?

LS: I was looking at the notes from her and her handouts (which she hand-wrote in pencil along with other suggestions). In re-reading them, I realized how much of an effect she had on me. She did not like transparent cuts. She wanted you to notice negative space and she wanted these edits to be fierce. She wanted you to be in the world of the film, which definitely reflects the notion of “every content leaves a trace.” Each is a world for me. It is a period of time. I remember working on SERMONS AND SACRED PICTURES [about the life and work of Reverend L.O. Taylor], the final film for my degree, which I finished in 1989. I said [to Gunvor Nelson], “I have been working on this for two years. I really want to finish it!” She said to me, “You’re going to miss it!” It is interesting that projects like these are gifts of immersion. Gifts of totality.

HTN: All of them—each person, each project—leaves a trace.

– Jonathan Marlow (@aliasMarlow), SV ARCHIVE [SCARECROW VIDEO] Executive Director