Starfish Colossus

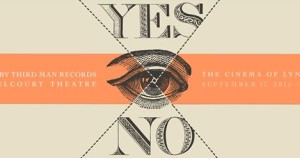

The Light and Sound Machine is at it again, bringing Nashvillians some of the most interesting experimental cinema, current and historical, screening anywhere in the Southeast. On Thursday, Sept. 17, L&SM welcomes veteran filmmaker Lynne Sachs for a program of works spanning her 30-year career, beginning with her first released film and ending with her latest.

Sachs is probably best known as an experimental documentarian, and the centerpiece of this program is one of her most widely screened films, the 45-minute featurette Investigation of a Flame. This 2003 work examines the legacy of the Catonville Nine, the anti-war protesters who in 1968 walked into the local offices of the Catonville, Md., Selective Service, stole their Vietnam draft files, and lit them on fire using homemade napalm. The group, led by radical priests Philip and Daniel Berrigan, became symbols of a different kind of war resistance, and Sachs’ film interviews those members of the Nine still living, intercutting the new material with file footage for a multi-perspectival approach.

Sachs’ earliest works are more “traditional,” if by this we mean operating in the recognizable vernacular of American avant-garde film. So for most viewers, they will seem quite unusual indeed. For example, “Still Life With Woman and Four Objects” (1986), Sachs’ first film, adopts a feminist approach common during the 1980s: Instead of offering a portrait of a woman per se, we are given mere fragments, and the promised objects of the title are either withheld or depicted in such an oblique manner as to make it likely that we will miss them. The upshot being: Any filmic subject, such as “woman,” is inherently too complex to adequately depict with straightforward means.

Similarly, Sachs’ four-image “Drawn and Quartered” (also 1986), is partly a self-portrait, partly a portrait of a man (presumably Sachs’ partner Mark Street), and partly a study of a shifting environment. The split image results from Sachs having shot in 8mm, but not having split the film in half (as was customary with regular 8, before Super 8 cartridges). So one gets a doubled, inverted image. The two double images play off one another in terms of form, direction and color. Their relationship is partly planned, but not entirely within Sachs’ control.

Two of Sachs’ films from the past decade focus on the filmmaker’s children, capturing moments of innocence and discovery. 2001’s “Photograph of Wind” is a brief portrait of Sachs’ daughter Maya as she runs and whirls in a circle. The silent black-and-white film shows the little girl surrounded by the centripetal streaks of spinning grass and trees, the runner and the camera going in and out of phase with one another. “Noa, Noa,” from 2006, depicts the young girl of the title playing dress-up in the woods, acting like a queen of the forest and exhibiting an enviable sense of self. Black-and-white and silent, like “Photograph of Wind,” “Noa, Noa” ends with a surprising coda in color with sound. It’s as if Noa’s world suddenly bursts into a new dimension of life.

Sachs’ latest, “Starfish Aorta Colossus” (made with Sean Hanley), is based on a poem by Paolo Javier. An eerie, fractured meditation on loss, the poem is visualized with another foray into multiplied imagery. Although formally “Starfish” echoes “Drawn and Quartered,” the new film features striking footage of the AIDS quilt, as well as partial, disrupted portions of bodies and landscapes. The structural play that enlivened Sachs’ film from 30 years ago is now mournful, staggered. This speaks not only to Sachs’ inevitable maturity as an artist, but no doubt to her assessment of the three decades we have collectively traversed to arrive where we are now.