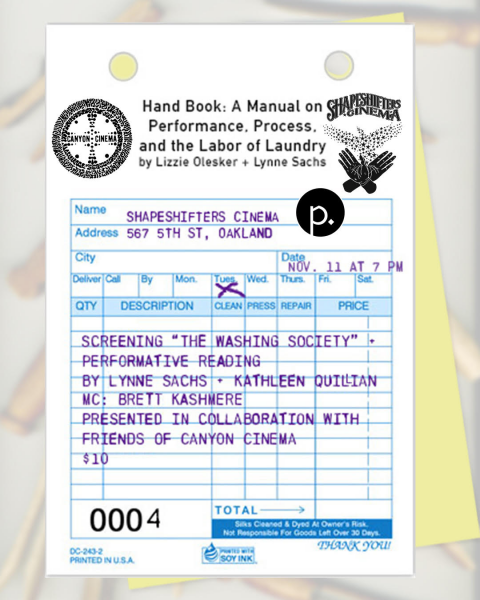

Lynne Sachs – The Washing Society + Hand Book: A Manual on Performance, Process, and the Labor of Laundry

7pm Tuesday, November 11, 2025

Shapeshifters Cinema, Oakland

https://canyoncinema.com/2025/10/14/lynne-sachs-the-washing-society-hand-book-a-manual-on-performance-process-and-the-labor-of-laundry-shapeshifters-cinema-nov-11-2025/

Co-presented by the Friends of Canyon Cinema

Admission: $10 (discount for Shapeshifters members; free for Friends of Canyon)

Event tickets here

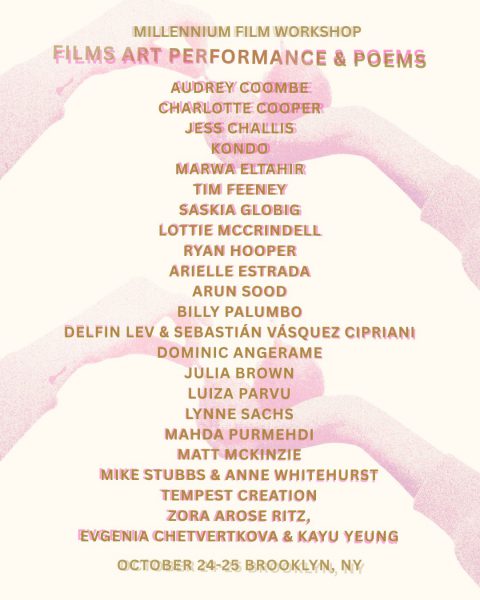

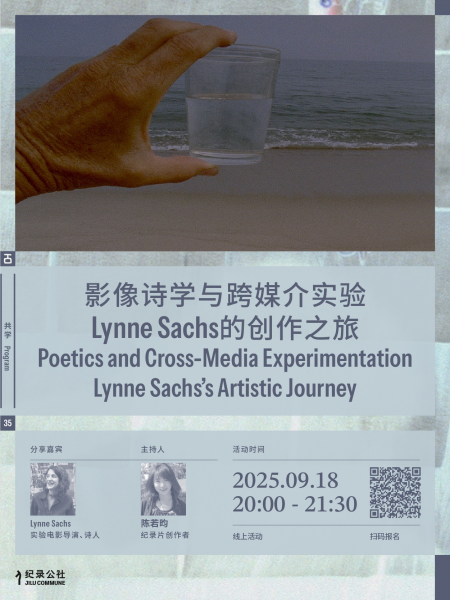

NYC-based filmmaker Lynne Sachs joins us for a deep, poetic dive into laundry—an area of focus she has examined over the past decade, through her film The Washing Society (co-directed with Lizzie Olesker) and a new book, Hand Book: A Manual on Performance, Process, and the Labor of Laundry, just released by Punctum Books.

Along with a screening of The Washing Society, Lynne will present a performative reading, with Shapeshifters Programming Director Kathleen Quillian, of excerpts from Hand Book as well as engage in a discussion about the book, film, and process with Canyon Cinema Executive Director Brett Kashmere.

Copies of the book will be available for purchase and can be signed by the artist after the event.

SHAPESHIFTERS CINEMA provides a venue and support for contemporary artists working with experimental and artist-made film, video, sound, music and other types of mediated performance. We host screenings and performances by local and visiting artists in our intimate 40-seat theatre and offer workshops on a variety of experimental and DIY moving image and sound production. Our storefront shop specializes in print publications, DVDs, sound recordings and other kinds of media made by artists who have screened or performed in our venue.

SHAPESHIFTERS BREWERY makes a variety of small-batch, seasonal, hand-crafted beers, brewed on-site in a space right behind the cinema. These are served (to 21+) at all our events as well as some off-site events. Find out more at shapeshiftersbrewery.com

SHAPESHIFTERS CAFÉ, is right next door to our cinema! We offer freshly-made salads, sandwiches, coffee, tea, pastries and more. Open Monday-Friday 6am-2pm and every Saturday 10am-2pm. Find out more at shapeshifterscafe.com