https://lalumierecollective.org/2024/the-film-makers-cooperative-experimental-rituals/

07.11.2024 | 7:30

7080, rue Alexandra, #506 Montréal, QC Canada

16mm & HD

Achats en ligne

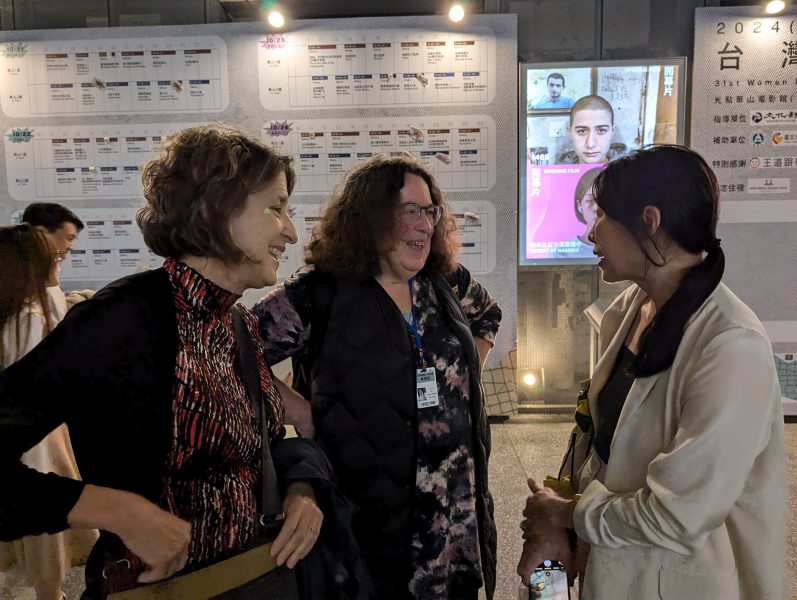

En présence de Jeremiah M. Carter, Sarah Viviana Valdez, Emily Singer

PROGRAMME

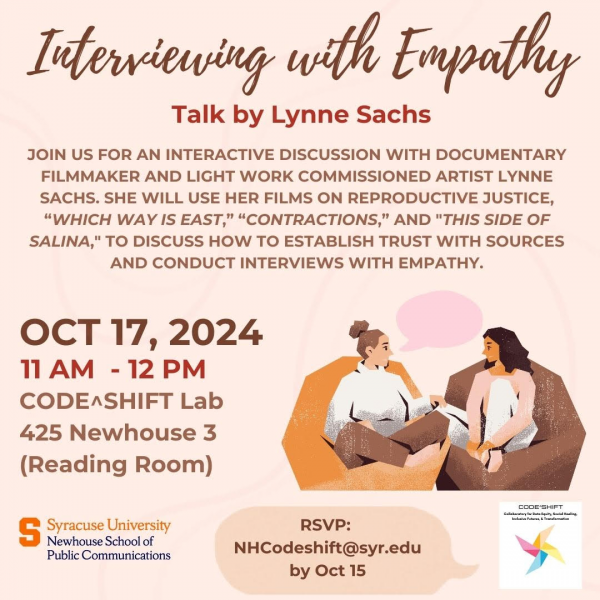

Proposed by Emily Singer, board director, this program showcases six films from The Film-Makers Cooperative, offering a fresh perspective on the Cooperative’s legacy by highlighting works beyond the well-known « greats. » These films represent a diverse range of voices and experimental approaches that push the boundaries of storytelling, exploring the complexities of womanhood, identity, and personal transformation. Through innovative uses of symbolism, surrealism, and poetic imagery, the filmmakers reimagine how female protagonists grapple with their inner worlds—struggling with guilt, desire, and societal expectations—while crafting narratives that blend the intimate with the universal. This selection underscores the Cooperative’s ongoing influence in expanding the language of cinema to explore more nuanced and marginalized experiences.

Each film in this program reflects a distinct, bold approach to experimental filmmaking, weaving together personal, cultural, and historical contexts. Whether engaging with themes of spiritual obsession, daily ritual, or self-reflective critique, these works challenge conventional narratives by offering deeper meditations on the female experience. By embracing abstraction, surrealism, and non-linear storytelling, the filmmakers create a space where emotion, identity, and transformation take center stage.

The Film-Makers’ Cooperative/New American Cinema Group (FMC/NACG) was founded in 1961 for the distribution of avant-garde film.

Who Do You think you Are

Mary FIllipo | 1987 | 16mm | 10 mins

In Who Do You Think You Are (1987, 10 minutes) the main character, a filmmaker, investigates her own cigarette smoking habit while wishing she could make “a film about injustice.” She wishes, in other words to do something heroic. She has been seduced by the image of the cigarette-smoking hero, but an image is only an image.

She drank vinegar from the river

Jeremiah M. Carter & Sarah Valdez | 2023 | HD | 25 mins

Shot on beautiful super 16mm and loosely based on the life of Saint Rose of Lima, She Drank Vinegar From The River, is the journey through a young woman’s mind while her absentee father begins to express concerns over her obsessions with Christ and Penance.

Mujer De Mifuegos

Chick Strand | 1976 | 16mm | 15 mins

A kind of heretic fantasy film. An expressionistic, surrealistic portrait of a Latin American woman. Not a personal portrait so much as an evocation of the consciousness of women in rural parts of such countries as Spain, Greece and Mexico; women who wear black from the age 15 and spend their entire lives giving birth, preparing food and tending to household and farm responsibilities. MUJER DE MILFUEGOS depicts in poetic, almost abstract terms, their daily repetitive tasks as a form of obsessive ritual. The film uses dramatic action to express the thoughts and feelings of a woman living within this culture. As she becomes transformed, her isolation and desire, conveyed in symbolic activities, endows her with a universal quality. Through experiences of ecstasy and madness we are shown different aspects of the human personality. The final sequence presents her awareness of another level of knowledge.

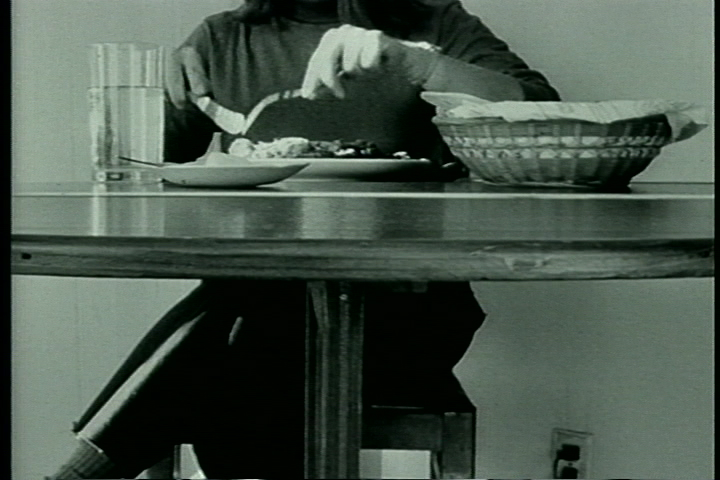

Still Life of Woman in Four Objects

Lynne Sachs | 1986 | 16mm | 4 mins

A film portrait that falls somewhere between a painting and a prose poem, a look at a woman’s daily routines and thoughts via an exploration of her as a “character”. By interweaving threads of history and fiction, the film is also a tribute to a real woman – Emma Goldman.

Tides

Amy Greenfield | 1982 | 16mm | 12 mins 25 secs

Camera: Hilary Harris; Performer: Amy Greenfield. The literary sources for TIDES came from Isadora Duncan’s « The Dance of the Future, » Maya Deren’s script for the unfilmed passages of Ritual In Transfigured Time, Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra. « TIDES is a cinema-dance dealing with the theme and image of woman and ocean. The entire film was shot with a high speed camera, creating action from two to twenty times slower than normal speed. Because of this extreme slow motion, the surge and flow of the woman’s nude body and the waves becomes intensely felt, continually moving cinematic imagery. « TIDES alludes to the very romantic confrontation of the human being and the elements as participants in a centuries-old drama. The film is introduced by a quote from Isadora Duncan’s ‘The Dance of the Future,’ and proceeds to visualize the woman – the filmmaker herself – first rolling into the heart of the wave, then moving with, against, under, into the waves, until, at the end of the film, her whole body shouts with joy. » – 16th Edinburgh International Film Festival Exhibition: London Film Festival, 1982; Edinburgh Film Festival, 1982; Museum of Modern Art, NY, 1983; NY Shakespeare Public Theatre, 1983.

From the Ladies

Holly Fisher | 1978 | 16mm | 20 mins

Filmed in the multiple-mirrored women’s powder room of the NYC Holiday Inn: a space simultaneously seductive and vulgar, in which the most visible image was myself looking at myself with Bolex in-hand. Here is a room exclusively my own, and so the site for slippery play between myself as subject, object, maker, and woman. Slow pans in wide sweeping arcs, capturing anyone walking through, transform to an abstract swirl of motion and emotion. Filmmaker at play with the gaze…

BIOGRAPHIES

Emily Singer is a business strategist and filmmaker based in Brooklyn, NY. Her films focus on women’s history told by women, for women. As President of the board of directors for the Film-Makers Cooperative, she is committed to preserving experimental cinema and fostering spaces for coexistence that challenge normative ideals through community-driven efforts. With a background in policy, design, community development, and urban sociology, Emily brings a multidisciplinary approach to all of her work.

Mary Filippo’s work focuses primarily on the self and its relation to inequality. In Peace O’ Mind (1983), the characters try to stay safe at home, but become isolated and entrapped there. Images of a domestic space are connected with images of poverty “in the backyard” of this space to suggest the knowing of and hiding from this deprivation has entrapped the characters, physically and mentally, in their private, isolated, and disturbed spaces. In Who Do You Think You Are (1986) the main character, a filmmaker, investigates her own cigarette smoking habit while wishing she could make a film about injustice. She wishes, in other words, to do something heroic. She has been seduced by the image of the cigarette-smoking hero, but an image is only an image. With Feel the Fear (1990, 24 minutes) Filippo links images and ideas about television viewing, self-help therapy, alcohol use, acting, mimicry and social responsibility with metaphoric and formal similarities to imitate connections of cause and effect; but the suggestion of causal logic doesn’t hold up and becomes increasingly skewed. The film’s structure is a metaphor for the contradictions of the culture in which it was made.

Jeremiah M. Carter is a writer, director, and musician from Nashville, Tennessee working between Brooklyn, New York and Austin,Texas. After dropping out of community college while studying philosophy, Jeremiah has gone on to compose multiple albums released throughout the world and direct films.

Sarah Valdez is an art writer who lives in New York and Los Angeles. She was very active in writing about the artists featured in Beautiful Losers with a focus on the artists of the Mission School. Her work has been featured in magazines including Art in America, Paper, Garage, and ARTnews, among others. Sarah Valdez was interviewed July 11, 2005 in New York, NY.

Mildred « Chick » Strand (1931 – 2009) was an experimental filmmaker, known for blending avant-garde techniques with documentary.

Since the 1980s, Lynne Sachs has created cinematic works that defy genre through the use of hybrid forms and cross-disciplinary collaboration, incorporating elements of the essay film, collage, performance, documentary and poetry. Her highly self-reflexive films explore the intricate relationship between personal observations and broader historical experiences. With each project, Lynne investigates the implicit connection between the body, the camera, and the materiality of film itself.

Amy Greenfield (born 1950) is a filmmaker and writer living in New York City. She is an originator of the cine-dance genre and a pioneer of experimental film and video.

Holly Fisher has been active since the mid-sixties as an independent filmmaker, printmaker, teacher, and film editor. She was the editor of Christine Choy and Renee Tajima-Peña’s feature documentary Who Killed Vincent Chin? –– nominated for an Oscar in 1989, and added to The National Film Registry of Library of Congress, 2021. Her experimental short works and long-form essay films –– explorations in time,memory, trauma, and perception –– have been screened in museums and film festivals worldwide including Whitney Museum Biennials; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Film Forum, Japan; and two world premieres in The Forum of the Berlinale, Germany. Selected grants include The Jerome Foundation, NYSCA, CAPS, and The American Film Institute. Her silent film Rushlight won the Grand Prize in the 1985 Black Maria Film Festival, and her feature Bullets for Breakfast received “Best Experimental Film Award” at the Ann Arbor Film Festival. Her solo retrospectives include The Museum of Modern Art(1995) and more recently at Anthology Film Archives (2019), each entitled THE FILMS OF HOLLY FISHER. Her new feature Out of the Blue, completed during cover lockdown, was premiered weekend of the 9/11 20th anniversary at Anthology Film Archives, September 2021, together with A Question of Sunlight–– Fisher’s experimental doc linking 9/11 with the Holocaust via the telling of downtown artist José Urbach, who was witness to both.