Interview: OBSERVE AND SUBVERT

BY INNEY PRAKASH

December 2021

https://metrograph.com/observe-and-subvert/

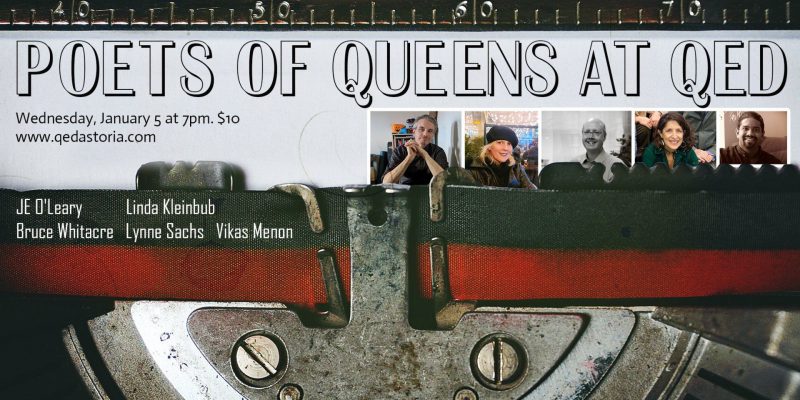

An interview with experimental documentary filmmaker Lynne Sachs.

Our Lynne Sachs Series plays at Metrograph December 10–12.

Several of her films are currently available to watch on the Criterion Channel

Whether portraying artists, historical figures, family members, or strangers, filmmaker Lynne Sachs has always found rivetingly indirect methods of representing her subjects. The San Francisco Weekly called her 2001 film Investigation of a Flame, about the Vietnam War and the Catonsville Nine, a group of Catholic activists who burnt draft files in protest, an “anti-documentary.” Sachs herself now uses the phrase “experimental documentary” as shorthand for describing the formal elements that constitute her particularly idiosyncratic and collage-like cinematic vernacular, notable in work like the decades-in-the-making Film About A Father Who (2020).

Rooted in her days in San Francisco’s experimental scene, Sachs’s concerns are deeply material; they regard the matter that makes up the world as inextricable from the technology that reproduces it. Her investigation of New York City laundromats, The Washing Society (2016), co-directed with playwright Lizzie Olesker, struck me as an apt departure point for our wide-ranging discussion about and around this material awareness, as well as the larger concerns that bridge the gap between her films as works of art and Sachs’s advocacy for worldly change.

I WANT TO START WITH A WEIRD QUESTION.

I like weird questions.

WHAT ARE YOUR THOUGHTS ON LINT?

I have been thinking about lint so much over the last few years. It started with my thinking about skin, and the epidermis, and about clothing being a second layer of our skin—which means that when we collect lint out of the dryer, we’re also catching aspects of our bodies. Sometimes it’s our own bodies, sometimes it’s the bodies of people we love. Sometimes it’s the bodies of people whose clothes are being washed in a transactional way…Iin that flow, you collect something most people think of as detritus. But I actually think of it as material, in the way that Joseph Beuys was really interested in wax and felt. So, lint is material for sculpture, and for an examination of our bodies. When that comes together, I find it very compelling.

I AM, OF COURSE, REFERRING TO A COUPLE OF SPECIFIC SHOTS FROM THE WASHING SOCIETY, WHICH EMPHASIZE SENSUOUSNESS, WHICH IS NOT A WORD I EVER WOULD’VE PREVIOUSLY USED TO DESCRIBE LINT.

That attention to the microscopic aspects that are residue of the much larger social relationships around service, hygiene, and the exchange of money for someone who performs something for somebody else—lint represents all those things.

IT MAKES ME THINK OF THE WASHING SOCIETY AS AN EXTENSION OF YOUR CAREER-LONG PREOCCUPATION WITH MATERIAL FILM, EVEN THOUGH IT WAS SHOT DIGITALLY.

When we look at traditional 16mm film, we see scratches and hair, like we see in lint. It’s not that different. Because lint collects through the months or ages, it collects aspects of the world. Film does the same thing; it is changed by its journey in time.

My co-director, Lizzie Olesker, and I wanted to figure out ways to examine the interplay between economics, aesthetics, and politics. You look at the form of cinema and you say, “I want to create ruptures. I want to create a radicalization of the way images are represented.“ But it’s also important to look not just at the way the camera reproduces our reality, but what is produced by the reality that might be dismissed or ignored. … Lint is not invisible, but it’s about as close to invisible as it gets. It moves from clothing to the trashcan in a kind of rote way. By breaking up that [journey], we’re trying to look at the mechanisms of labor.

THE WASHING SOCIETY FEATURES ACTUAL LAUNDRY WORKERS AND ACTORS. WHAT IS IT ABOUT THIS ASPECT OF PERFORMANCE THAT FASCINATES YOU AS A DOCUMENTARIAN?

It occurred to me about a year ago that every single film is a document of a performance. Even a fiction film, which is a bunch of people doing this crazy thing—to reinvent themselves, pretend that they’re different from who they are—we film it, and it’s called a fiction film, but it’s actually a documentary of a group of people together.

What’s started to interest me in the last year is that woven quality that takes seriously that anyone in, for example, a documentary film is performing an aspect of who they are. As soon as they turn their head and they see the camera, they’re performing. And there’s this, you could call it a leash, or an invisible thread [that runs] between my eyes and the eyes of any human being in front of the camera. They’re always looking to the director for some kind of affirmation, like, “Yes, you’re doing a good job.“ It’s the same in documentary. If you actually recognize that this is a form of exchange, then you can try to subvert it. People who are supposed to be ‘real’ become performers, or we have performers who open up about their lives . And so, obscure that rigid differentiation. That’s why I’m not really happy with the term ‘hybrid’ yet. Because it’s saying that this ontological conundrum doesn’t really exist, and that we have to create another category that says, “That’s ambiguously real and that’s ambiguously fiction.“

IN TERMS OF REAL-LIFE SUBJECTS VERSUS HIRED PERFORMERS, HOW DID YOU APPROACH WHO WOULD EXPRESS WHAT IN THE WASHING SOCIETY? THERE ARE TIMES, ESPECIALLY EARLY ON, WHEN IT ISN’T NECESSARILY CLEAR WHO IS WHO.

With filmmaking, there’s always two answers. There is the production answer: we tried one thing and it didn’t work, so we decided to go another way. And then there’s the more theoretical, maybe conceptual answer.

I WANT BOTH ANSWERS. I’M HUNGRY FOR ANSWERS.

Okay, the conceptual answer first. We wanted to research the experience of what it is to wash the clothes of another person. Particularly in a big city, where people and workplaces can be taken for granted. Lizzie comes out of playwriting, and this notion that you observe the world in which you live, and then you re-create characters who inhabit those experiences you’ve witnessed, or those interactions that confuse you, and that you’re trying to grapple with. And I come out of experimental filmmaking, with documentaries. So you observe and then you subvert.

She asked me if I would help her to investigate laundry workers in New York. We started, and we got really hooked, but most of the people who do this kind of service work in America are also immigrants, and many don’t have the formal paperwork to give them the freedom to be on camera, to talk about the struggles of their workplace or their bosses, who they’re supporting, all those things. So we would have very informal conversations, but we couldn’t record and we couldn’t film.

Our answer was not to give up, but to listen really actively, and then to write the characters, or to write three characters who appear in the film as composites of these conversations. So, there’s Ching Valdes-Aran, Jasmine Holloway, and Veraalba Santa. They’re all performers—the film started as a performance called Every Fold Matters, which we did live in laundromats in Brooklyn and in New York City, and at places like University Settlement, The Tank.

But then, okay, the answer to the conceptual side is that, even though I’ve been making work that you could call reality-based or documentary-based for a long time, I’m always questioning this notion of asking people to open up their lives for me. That’s why I made Film About a Father Who, because I felt like it was my turn to be in that vulnerable position.

One thing I’ve done for years now, I always pay people [who appear] in my films. That’s kind of anathema in documentary. People don’t do that. Especially journalists, which I do understand… But why shouldn’t you pay them the way you would pay an actor?

Often we measure the success of a documentary by how real it is, by the spontaneity of the reveal of information; “I can’t believe you got in that door.“ Or, “I can’t believe you got those people to say that for you with your camera on.“ There’s a lot of registers of success that have to do with the people in front of the camera letting it all hang out, and that’s an awkward exchange… I wanted to have people who felt confident in their place in the world, to speak from that position. If people didn’t feel confident, then we listened, and we tried to embrace their sentiments and struggles in a fictionalized way.

ARE THE ACTORS REPEATING TEXT THAT WAS SPOKEN BY ACTUAL LAUNDRY WORKERS OR WAS THAT TEXT WRITTEN BY YOU AND LIZZIE?

It’s both. We used parts of it, but often we wrote in a more free-form way. It’s really a composite, and there’s a freedom that comes from making a film like this. .. I call it the Maggie Nelson effect, [which is] this idea where you lay bare the research. In The Argonauts, she tells this personal story about her relationship, and she has these fantastic tangents, which are about her research, what she happened to be reading, letting all of that come in.

I can [also] say that we were influenced by Yvonne Rainer. She was such a visionary when it came to choreography, and a celebration of the body through dance. Because she looked at the quotidian, and she ‘deconstructed’— in the word of that period— how we move through the world. We took that approach to how we thought about the dance movements in The Washing Society, how we could re-examine the gestures of the everyday, and think about how they might be beautiful, in the way that Roberta Cantow’s film Clotheslines celebrates the beauty of laundry work. [Lizzie and I] wanted to think about recognising washing as a form of physical dance. Especially because there’s so much repetition, which dance also uses.

CLOTHESLINES HAPPENS TO BE PLAYING ALONGSIDE THE WASHING SOCIETY.

Clotheslines is fantastic. It’s giving attention, again, to urban life, and to things that people do that maybe they feel ashamed of doing but that they have to do. It’s interesting to look at Roberta Cantow’s film, because it’s a twist on the whole idea of being a feminist. Barbara Hammer did something similar; I think the term ‘feminist’ is evolving all the time.

What Roberta Cantow did in her work, I think, is say, “Let’s acknowledge the beauty of what mostly women do. But it doesn’t mean that they’ll become stronger women than when they don’t do it.” … I should add that today I had a conversation with Roberta Cantow. A woman she knew who organizes washerwomen in New York City told her about the screening. Anyway, she told me today that this whole group of organizers around washerwomen, 10 of them, are coming to Metrograph.

THAT’S EXTRAORDINARY.

Yeah. And I’m hoping [for] a group from the Laundry Workers Center, which is a union I’ve done a lot of work with, who organize workers in the small laundromats all over New York City… If they’re trying to shut down a laundromat or bring attention to conditions that are really, really bad—where people are required to work 12 hours, and they can’t look at their phones, or all the different rules that are had—[Lizzie and I] make videos for them sometimes.

DO YOU CONSIDER FILMMAKING AS A FORM OF ACTIVISM, OR ADJACENT TO IT? WHERE DO THE TWO INTERSECT?

I was thinking about this last night. I went to an event at E-flux, and I was listening to Eric Baudelaire, the filmmaker, talking about this too…. I don’t think I’ve ever made a film that had the ability to make someone act differently, or to push them in a direction. But I always hope it makes them think about who they are differently, or about how the world works in another way. Maybe the result of that would be an action. But if it’s just a thought, that’s pretty good too. I guess it has to do with results, how you measure your reach… I get very excited, like with Investigation of a Flame, by people doing things with passion, and pushing themselves to extremes from which they can never turn back. I mean, that actually goes to Barbara Hammer. [She] lived life to its fullest, and with so much conviction.

BEING IN DIALOGUE WITH OTHER ARTISTS, FILMMAKERS, OTHER PEOPLE, SEEMS SO ESSENTIAL TO ALL OF YOUR WORK.

Well, when I made Which Way Is East (1994), I didn’t at first understand that it really is about how we look at history, and how we analyze or reconstruct the past. That film is made from the perspective of myself and my sister. We were children who experienced the Vietnam War through television, mostly black-and-white images on a box in the living room. Being typical American, middle-class kids, our parents and their friends had not gone to war. The war was really far away… But you then grow up and you realize that it does touch you; you heard all the numbers of people who died, and you recognize that those statistics were always emphasizing the Americans, but what about the Vietnamese? How does war have an impact?

When we made the film, in the early ’90s, my sister, Dana Sachs, was living in Vietnam. I visited for one month, and, like a typical documentary filmmaker, you arrive in a place and you say, “I’m going to make a film.“ It came to me later that the film is a dialogue with history, but it’s also a dialogue between two women from the same family, who thought about that past in extremely different ways. She looked at Vietnam in this contemporary way, as survivors. Whereas I looked at Vietnam with this wrought guilt, trying to piece together an understanding of a war that still seemed to bleed. That’s what gave the film its tension, that our perceptions were so different. Ultimately the most interesting films are the ones that ask us to think about perception, that don’t just introduce new material.

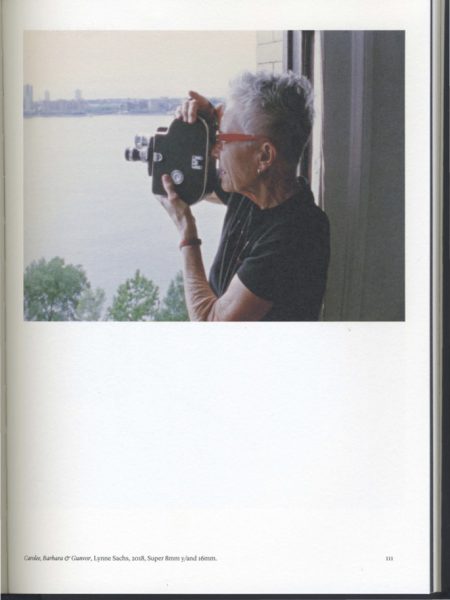

So that was a gift, to be in dialogue with my sister… Another way of looking at dialogue, [if] you’re in dialogue with [someone like] Jean Vigo, who’s not alive… then you’re creating a dialectic between the materials. In A Month of Single Frames, I’m in dialogue with Barbara Hammer literally, but I’m also in dialogue with her through the form of the film, and with the audience. That was intentional, to have this ambiguity.

In A Month of Single Frames, she also does something that’s not about activism, it’s about solitude… thinking about her place in nature. It’s all about being delicately and boldly in the landscape. When she cuts up little pieces of gel and puts them on blades of grass, she’s doing the opposite of what a feature film made in Cape Cod would… You’d have all these people stomping on the dunes, getting permission to shoot, to take over a whole house, you’d need light, electricity… She wanted to do everything with the least impact. It’s not a film that she probably announced as a celebration of the environment. But to me, it is so much about not leaving your footprint on the land, but being there. I really admire that work.

DID YOU BEGIN THE FILM BEFORE SHE DIED?

The last year of Barbara Hammer’s life, she gave footage to filmmakers and said, “Do whatever you want, and in the process use this material that I love but could not finish. Because I can see that my life will not last long enough to do so.“

She gave me footage from 1998, which she had shot in a residency on Cape Cod. I asked her why she didn’t finish this film and she said, “Because it’s too pretty, and because it’s not engaged, it’s not political.“ She felt that the fact that it delivered so much pleasure just in its loveliness made it problematic. It was this gorgeous landscape, and a woman alone in a cabin. She thought there wasn’t a rigor to it. So she had never done anything with it; it just moved around with her, and it was bothering her, of course: “Finish me. Finish me.“

She gave it to me, and I started to edit. On the second visit, I showed it to her, just without any sound. I asked if she did any writing while she was there, and she said, “I kept a journal.“ She’d forgotten all about it, so she pulled it out.

THAT’S THE DIALOGUE WE HEAR IN THE FILM?

She even writes about herself in the third person, which is fun, and different…

Everything was so pressured: she had to go to chemotherapy, she was trying to finish Evidentiary Bodies, a film that she was going to show at the Berlin Film Festival in 2019. It was one of the last things she did. So I had the material, and when she died… I needed to finish it. That’s when I wrote the text, because I needed to be in dialogue with her more than just editing the material. I needed to concentrate on that energy between us.

SO YOU COMPLETED A FILM YOU HAD BEGUN WORKING ON WHILE SHE WAS LIVING, AND THAT SHE DIED DURING THE MAKING OF. AND THEN YOU MADE A FILM IN DIALOGUE WITH SOMEONE WHO HAD ALREADY DIED, IN E•PIS•TO•LAR•Y: LETTER TO JEAN VIGO.

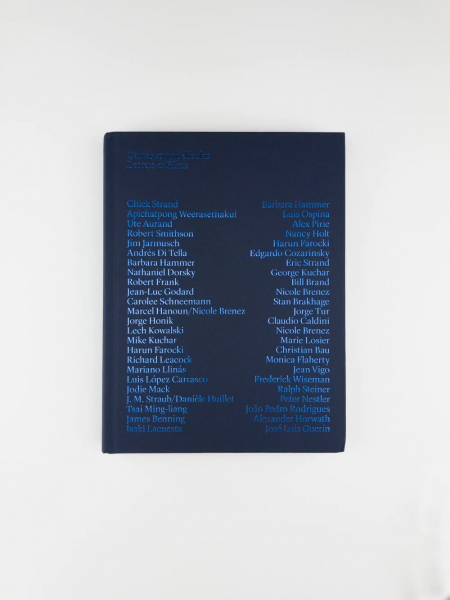

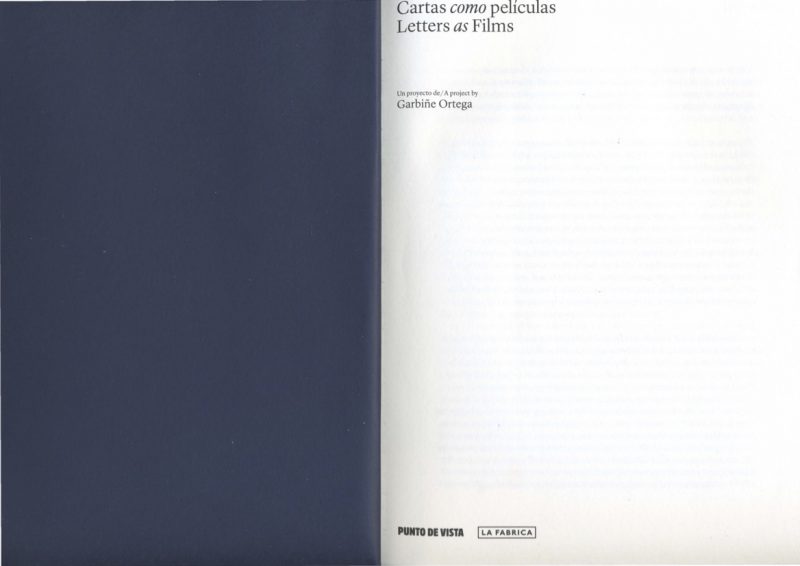

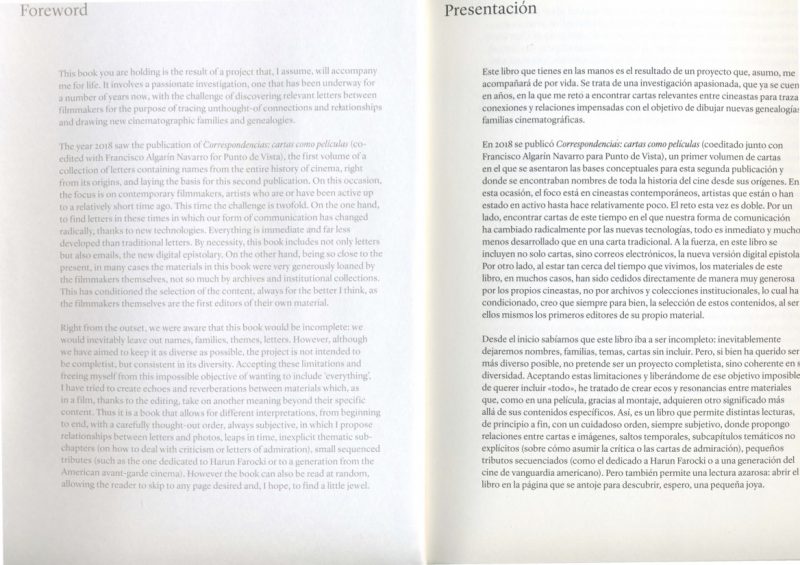

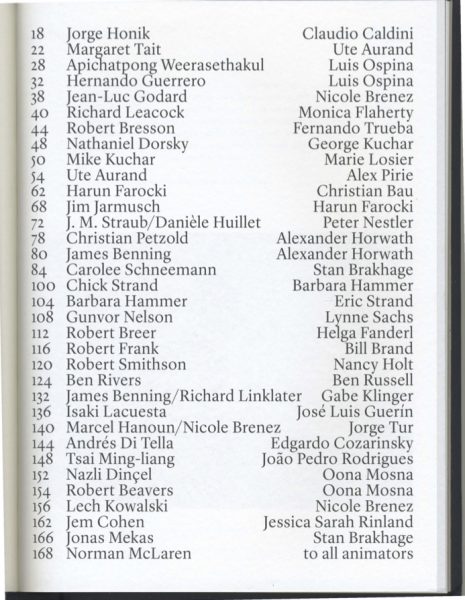

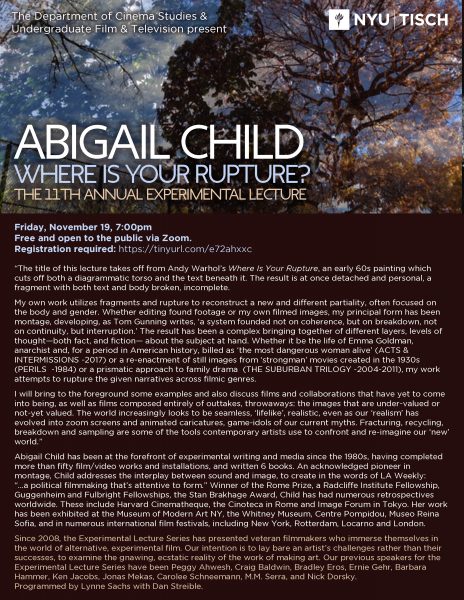

I’ll give you a little background. I’ve been on and off involved with the Punto de Vista Film Festival, which is a really interesting small festival in Pamplona, Spain, where they acknowledge and appreciate alternative ways of looking at documentary film practice. They asked 10 filmmakers to make a film in the form of a letter to a filmmaker who had influenced us.

I chose Jean Vigo; I love his film, Zero for Conduct (1933), because it is so much about rule breaking. It is so much about trying to exist in society, but knowing when there is a time to break the law. I had made my film Investigation of a Flame; I was interested in those moments where you have to turn inward and say, “This is wrong.“ And I wanted, again, to talk to a ghost. To talk to Jean Vigo.

Then, right at the beginning of this year, there was the attack on the US Capitol. A group of thousands chose to break the law, with absolute abandon in terms of the sacredness of other people’s bodies. I’m not even saying the US Capitol is sacred. But to go to a place of heinous destruction, that really disturbed me. I was already thinking about Jean Vigo, and I thought, “This is really complicated.” Because at what point do we learn to understand how to respect, how to have compassion, how to have empathy? That you can break rules, as in paint graffiti or burn draft files, but that once you start invading another person’s body— it’s a violation I couldn’t accept. And this space between anarchy and authoritarianism, and between compassionate rule breaking and violence was very interesting to me.

WHAT ABOUT REVOLUTION? WHAT ABOUT A FEMINIST SOCIALIST REVOLUTION?

Oh. Well I have to say, a feminist socialist revolution probably would come with a lot of compassion. I think, I hope. But I would never say that women… I don’t think that there’s anything innate.

One other thing about E•pis•to•lar•y: I really like all the syllables in epistolary, so I like that it sounds like bullets. And yet it’s about dialogue… It may be silent, but audiences are writing back in their heads. I think a lot about that in my filmmaking, all the sounds that go on in audiences’ minds.

ARE THE SUBJECTS OF INVESTIGATION OF A FLAME (2001), THE CATONSVILLE NINE, YOUR MODELS THEN OF RIGHTEOUS DISSIDENTS?

My interest in people who break the rules goes way back. I mean, I was protesting the implementation of imposing draft registration on American men when I was in high school. I’ve always been committed to trying to articulate a critique. But when I heard about the Catonsville Nine and this group of people who had nothing to gain by criticizing the US government’s presence in Vietnam, except that they were so upset that they felt they had to speak out against it…

They were Catholic antiwar activists: two priests in particular, Daniel and Philip Berrigan, and a nurse, and a sister, and others. But they broke the law in the most performative way. To take draft papers and burn them [with] napalm…. Napalm is not that different from lint. It’s just soap mixed with chemicals. You can make napalm at home. It’s domestically produced napalm, which was being used in Vietnam. But [the Catonsville Nine] wanted to make it and burn it symbolically. This, to me, was the ultimate art performance piece. Let’s burn files, photograph it, disseminate it, and say that these files represent bodies.

People said that they changed so much thinking. It was effective because it was an image that… You were asking about activism, that’s an image! To see priests burning draft files, that’s going to change things. That’s real activism on their part, and that happened in the 1960s.

FROM LINT TO NAPALM. THANK YOU, LYNNE.

I never thought… But it’s made with soap!

Inney Prakash is a writer and film curator based in New York City and the founder/director of Prismatic Ground.