Critic’s Pick! “[A] brisk, prismatic and richly psychodramatic family portrait.”

– Ben Kenigsberg, The New York Times

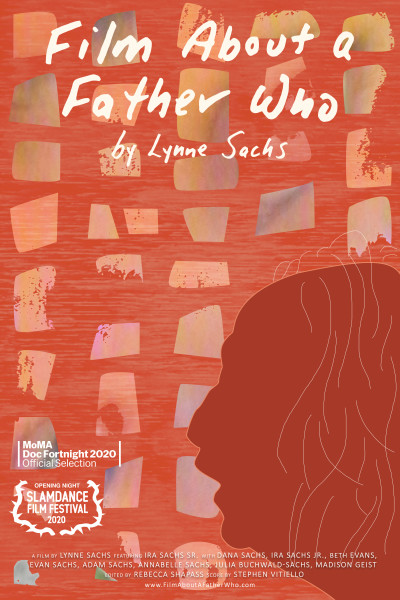

Film About a Father Who

74 min. 2020

Directed by Lynne Sachs

Feb. 17: one week link to film

Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/358398460

Password: FAAFW2021

Distribution:

http://www.cinemaguild.com/theatrical/filmaboutafatherwho.html

*World Premiere: Slamdance Film Festival 2020

Opening Night Film

https://slamdance2020.eventive.org/schedule/5dfd772e5f8abf00dc6dc0bd

Park City, Utah

Documentary Fortnight:

The Museum of Modern Art’s Festival of Non-Fiction Film

https://www.moma.org/calendar/events/6412

New York City

International Premiere:

Sheffield International Documentary Film Festival

https://sheffdocfest.com/films/6949

United Kingdom

Screenings:

Indie Memphis Opening Night Film 2020, Oxford, Sarasota, Rencontres Internationales du Documentaire Montréal (RIDM), DocAviv 2020, Israel; Gimli Film Festival, Canada; American Fringe Festival, Paris; Bend Film Festival, Oregon; DocLisboa, Portugal; San Francisco Jewish Film Festival; DocPoint Tallin, Estonia, 2021; Festival de Cine International Costa Rica, 2021; 57a Mostra Internazionale del Nuovo Cinema / Pesaro Film Festival 2021; Vox Feminae Festival, Zagreb, Croatia, 2021; Dead Center Film Festival 2021, Oklahoma; Athens Film and Video Festival 2021, Mimesis Documentary Festival, Boulder, Colorado, Opening Night 2021; Buffalo International Film Festival, 2021; Cine Documental Contemporáneo Realizado con Arhiva Doméstico, Bilbao Arte 2021, Spain; Centre Film Festival, Pennsylvania; A4 – Space for Contemporary Culture, Bratislava, Slovakia, 2021; Cinémathèque Français, Paris 2021; Festival International de Cine Contemporáno Camara Lucida 2021; Cork International Film Festival, Ireland Artist Focus presented by Artist and Experimental Moving Image; Metrograph Theater, New York City 2021.

“Film About A Father Who” was Featured on 9 Best Films of 2021 Lists:

• Roger Ebert: Selected by Simon Abrams & Matt Zoller Seitz

• The Film Stage: Best Documentaries of 2021

• Film Comment: Selected by Ela Bittencourt, Mackenzie Lukenbill, and Chris Shields

• Screen Slate: Selected by Anthony Banua-Simon, Nellie Killian, and Chris Shields

Criterion Channel streaming premiere with 7 other films, Oct. 2021.

Documentary Feature Award, Athens Film and Video Festival, Oct. 2021.

Best Feature Documentary Audience Award, Mimesis Documentary Festival, Jan. 2022

Selected Virtual Theaters:

Laemmle Theaters, Los Angeles; Roxie Theatre, Los Angeles; Philadelphia Film Society; The Belcourt, Nashville; Utah Film Center, Salt Lake City; Cleveland Cinematheque; Brattle Theatre, Cambridge, MA; Northwest Film Forum, Seattle; Facets, Chicago; Cine-File, Chicago; Austin Film Society; The Cinematheque, Vancouver, BC; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Maysles Cinema, NYC.

Download Press Kit PDF here:

Film About a Father Who Press kit 2020

Film About a Father Who website: www.filmaboutafatherwho.com

Synopsis

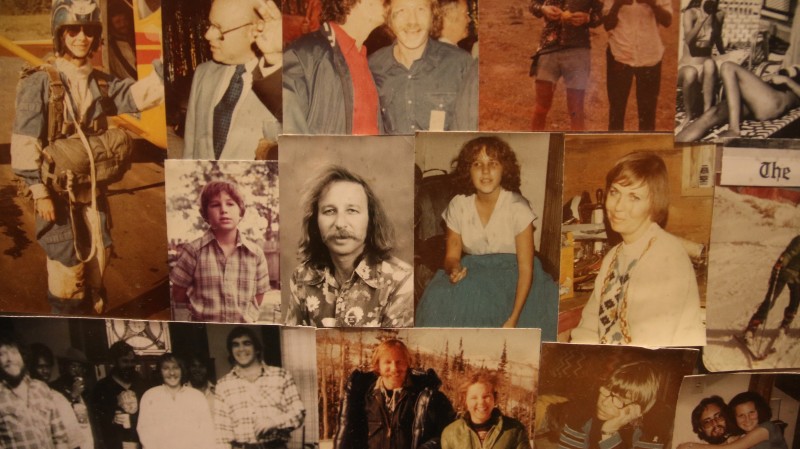

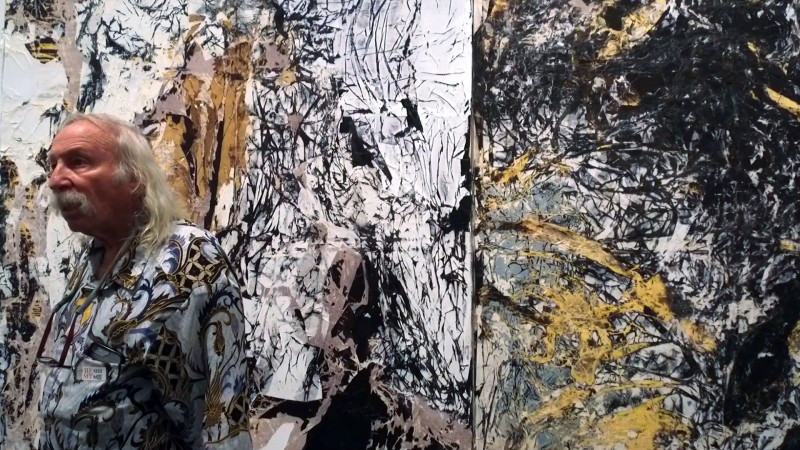

Over a period of 35 years between 1984 and 2019, filmmaker Lynne Sachs shot 8 and 16mm film, videotape and digital images of her father, Ira Sachs Sr., a bon vivant and pioneering businessman from Park City, Utah. FILM ABOUT A FATHER WHO is her attempt to understand the web that connects a child to her parent and a sister to her siblings. With a nod to the Cubist renderings of a face, Sachs’ cinematic exploration of her father offers simultaneous, sometimes contradictory, views of one seemingly unknowable man who is publicly the uninhibited center of the frame yet privately ensconced in secrets. In the process, Sachs allows herself and her audience inside to see beyond the surface of the skin, the projected reality. As the startling facts mount, Sachs as a daughter discovers more about her father than she had ever hoped to reveal.

“FILM ABOUT A FATHER WHO is a personal meditation on our dad, specifically, and fatherhood and masculinity more generally. The film is one of Lynne’s most searingly honest works. Very proud of my sister, as I have been since we were kids, and so deeply inspired.” – Filmmaker & brother, Ira Sachs, Jr.

Press Quotes

Sachs achieves a poetic resignation about unknowability inside families, and the hidden roots never explained from looking at a family tree.

—Robert Abele, Los Angeles Times

“Explores the complexities of a disparate family and a nexus of problems revolving around a wayward, unconventional, elusive patriarch…formidable in its candour and ambition.”

—Jonathan Romney, Screen International

“In Film About a Father Who … Sachs never seems to intimate that her perspective is universal but, rather, that having a perspective is.”

—Kat Sachs, MUBI Notebook

“Sachs goes to places that most … moviemakers avoid, undercutting the image of the past as simpler or more stable than the present.”

-—Pat Brown, Slant Magazine

“(Sachs’) own practice can be understood as a process of grammatical excellence; each thought, memory, scene, time and space given pause and punctuated by still more dancing light.” In Film About a Father Who, (she) admits that she is filming as a way of finding transparency. It is the ultimate in searching for cinematic veracity. She finds something beautiful and deeply moving, here…. Film About a Father Who is her greatest achievement yet.”

—Tara Judah, Ubiquarian

“This divine masterwork of vulnerability weaves past and present together with ease, daring the audience to choose love over hate, forgiveness over resentment. Sachs lovingly untangles the messy hair of her elusive father, just as she separates and tends to each strand of his life. A remarkable character study made by a filmmaker at the top of her game– an absolute must see in Park City.”

—Michael Gallagher, Slamdance Programmer

“Here we have a family. And most families have fall-outs. And the ruptured and the intense one in Lynne’s film—amazing documentary—reveals how far blood lines can stretch without losing connection altogether. Though this is an extremely personal film, and asks us several times to really choose between love and hate, she’s really exploring a universal theme that we all think about from time to time, which is the extent to which one human being can really know another. And in this case, it’s her dad.“

—Peter Baxter, President and co-founder of Slamdance speaking on KPCW Radio, Park City, Utah

“The film is bookended with footage of Lynne Sachs attempting to cut her aging father’s sandy hair, which — complemented by his signature walrus mustache — is as long and hippie-ish as it was during the man’s still locally infamous party-hearty heyday, when Ira Sachs Sr. restored, renovated and lived in the historic Adams Avenue property that is now home to the Mollie Fontaine Lounge. ‘There’s just one part that’s very tangly,’ Lynne comments, as the simple grooming activity becomes a metaphor for the daughter’s attempt to negotiate the thicket of her father’s romantic entanglements, the branches of her extended family tree and the thorny concepts of personal and social responsibility.”

—John Beiffus, Memphis Commercial Appeal

“’Film About a Father Who,’ whose title was inspired by Yvonne Rainer’s ‘Film About a Woman Who…,’ is a consideration of how one man’s easygoing attitude yielded anything but an easy family dynamic as it rippled across generations. The movie runs only 74 minutes, but it contains lifetimes.“

—Ben Kenigsberg, The New York Times

Photos

Poster

Film About a Father Who on 9 Best Films of 2021 Lists

RogerEbert.com

https://www.rogerebert.com/features/the-individual-top-tens-of-2021

The Film Stage

https://thefilmstage.com/the-best-documentaries-of-2021/

Film Comment

https://www.filmcomment.com/best-films-of-2021-individual-ballots/

Screen Slate Best Movies of 2021: First Viewings & Discoveries and Individual Ballots

https://www.screenslate.com/articles/best-movies-2021-first-viewings-discoveries-and-individual-ballots#sun

Press

- Film About a Father Who: Mimesis 2021 Best Feature Documentary Audience Award – Jan. 24, 2022

https://www.colorado.edu/center/cdem/2022/01/24/mdf-2021-review - Direct Link to Slamdance Listing for film

https://slamdance2020.eventive.org/schedule/5dfd772e5f8abf00dc6dc0bd - Screendaily – Dec. 18, 2019

“Slamdance 2020 to open with ‘Film About A Father Who”

https://www.screendaily.com/news/slamdance-2020-to-open-with-film-about-a-father-who/5145762.article - Deadline – Dec. 18, 2019

Slamdance Sets “Film About a Father Who” to Open 2020 Festival

https://deadline.com/2019/12/slamdance-2020-film-about-a-father-who-opening-night-1202812307/ - Salt Lake Tribune – Dec. 18, 2019

Park City Developer Ira Sachs, Sr. will be Profiled in Slamdance’s Opening Film

https://www.sltrib.com/artsliving/2019/12/18/park-city-millionaire/ - KPCW Local News Hour with Leslie Thatcher – Park City NPR

Jan. 3, 2020 Live Radio Interview with Lynne Sachs

https://www.kpcw.org/post/local-news-hour-january-3-2020?fbclid=IwAR3IapOdDy-ph-m1AlaGsmzf0qQSJkNboEU1N6EK6opd22RLqG5A6fgN9Po#stream/0 - Variety: Museum of Modern Art’s Doc Fortnight Lineup

Jan. 7, 2020

https://variety.com/2020/film/news/museum-of-modern-arts-doc-fortnight-lineup-includes-crip-camp-some-kind-of-heaven-exclusive-1203457929/ - KPCW – Morning News with Leslie Thatcher, Park City

20 min. Interview w/ Lynne Sachs begins at 20:18 – Jan. 5, 2020

https://www.kpcw.org/post/local-news-hour-january-3-2020#stream/0 - KPCW – Slamdance Opens with Documentary on Park City Denizen (close transcription of radio interview) – Jan. 7., 2020

https://www.kpcw.org/post/slamdance-2020-opens-documentary-park-city-denizen-ira-sachs#stream/0 - “Memphis writer, filmmaker Lynne Sachs returns this week with new book of poetry” by John Beiffus

Memphis Commercial Appeal, Jan. 8, 2020

https://www.commercialappeal.com/story/entertainment/arts/2020/01/08/lynn-sachs-memphis-year-by-year-poems/2832335001/ - WBAI 99.5 Radio in NYC & Pacifica Affiliates “Arts Express” (Global Arts Magazine) with Host Prairie Miller – start at 29 min. 22 sec. – Broadcast week of Jan. 13 and is archived here:

https://www.wbai.org/archive/program/episode/?id=9151 - Salt Lake Tribune: “Slamdance Festival’s Opening Film Features A Daughter Exploring Her Father’s Secrets” by Sean P Means, Jan. 19, 2020

https://www.sltrib.com/artsliving/2020/01/19/daughter-explores-her/ - Talkhouse: “In Celebration of the Darkness: What Can Happen When the Lights Go Out” by Lynne Sachs Jan. 22, 2020

https://www.talkhouse.com/in-celebration-of-the-darkness-what-can-happen-when-the-lights-are-out/?fbclid=IwAR05sbxtV_EGibdG6cnOk4xURvaNUYNNFgL6wS-uCjUYiTmHRXih9_yKzh8 - Park Record: “Park City’s Enigmatic Business Man Ira Sachs is Subject of Slamdance Opener” by Scott Iwasaki

https://www.parkrecord.com/entertainment/park-citys-enigmatic-businessman-ira-sachs-is-subject-of-slamdance-opener - Grasshopper Films “Transmissions – “Single Take: Lynne Sachs on Godard” – Jan. 23, 2020

https://grasshopperfilm.com/transmissions-sachs/ - Moveable Fest – “Lynne Sachs on a Subject Feeling Close Enough to Feel Far Away” by Stephen Saito – Jan. 23, 2020

http://moveablefest.com/lynne-sachs-film-about-a-father-who/ - Filmwax: Podcast Interview with Lynne Sachs by Adam Schartoff – Jan. 23, 2020

http://www.filmwaxradio.com/podcasts/episode-595/ - Salt Lake Dirt: Interview with Lynne Sachs by Kyler Bingham – Jan. 24, 2020

https://saltlakedirt.com/f/an-interview-with-filmmaker-lynne-sachs - Filmmaker Magazine: “‘Forgiveness is a Big Part of the Movie’ Director Lynne Sachs on her Slamdance Premiering Doc” by Daniel Egan – Jan. 24, 2020

https://filmmakermagazine.com/108861-forgiveness-is-a-big-part-of-the-movie-director-lynne-sachs-on-her-slamdance-premiering-doc-film-about-a-father-who/#.XitlJxd7kqJ - Unseen Films- Review of Film About a Father Who by Steve Kopian – Jan. 24, 2020

http://www.unseenfilms.net/2020/01/film-about-father-who-2020-slamdance.html - Hammer to Nail Review of Film About a Father Who by Christoper Reed – Jan. 26, 2020

https://www.hammertonail.com/reviews/film-about-a-father-who/ - The Fog of Truth, a podcast about documentaries, Jan. 29, 2020. Podcast “Episode 801: Slamdance 2020” – Chris Reed and Bart Weiss interview Lynne Sachs (Click “episodes” to Listen to the interview)

https://www.fogoftruth.com/current-news/2020/1/29/episode-801-slamdance-2020 - KCPW 88.3FM, The Daily Buzz & Bitch Talk, Jan. 30, 2020. Interview with Lynne Sachs hosted by John Wildman

http://kcpw.org/blog/daily-buzz/2020-01-30/the-daily-buzz-from-sundance-day-4-1-30-20/ - Directed by Women: Interview with Lynne Sachs, Feb. 3, 2020

https://directedbywomen.com/lynne-sachs-exploring-the-making-of-film-about-a-father-who/ - New York Times: “4 Film Series to Catch in New York This Weekend” by Ben Kenigsberg, Feb. 5, 2020.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/06/movies/nyc-this-weekend-film-series.html - Nina Rothe, Film, Fashion, Life: “This is not a portrait”: Lynne Sachs’ must watch ‘Film About a Father Who’ screens in NYC

https://www.eninarothe.com/movies/2020/1/24/lynne-sachs-film-about-a-father-who - This Week in New York: Review of Film About a Father Who by Mark Rifkin, Feb. 9. 2020

http://twi-ny.com/blog/2020/02/09/doc-fortnight-film-about-a-father-who/ - Go Indie Now: “Slamdance 2020 Bio Docs” Review of Film About a Father Who by Joe Compton, Feb. 10, 2020

https:// goindienow.com/home/slamdance2020_pt1 - Go Indie Now: Interview with Lynne Sachs on “Film About a Father Who”, Feb. 11, 2020

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wAf0_9aWGHw&feature=youtu.be - Women & Hollywood: “Collaboration Taught Me Different Ways of Making Films and Seeing the World” by Lynne Sachs, Feb. 10, 2020

https://womenandhollywood.com/guest-post-collaborating-taught-me-different-ways-of-making-films-and-seeing-the-world/ - agnès films: Supporting Women & Feminist Filmmakers – Review by Alexandra Hidalgo, Feb. 13, 2020

https://agnesfilms.com/reviews/review-of-lynne-sachs-film-about-a-father-who/?fbclid=IwAR0Q7f5zXkuSGJ6q3F7-FV0hc10Rsasex0Tt8qQguyoIK8TtSF0CjIgK4Y8 - The Pop Break: “Film About a Father Who Review: A Film as Ambiguous as Its Subject”

https://thepopbreak.com/2020/02/14/film-about-a-father-who-review-as-ambiguous-as-its-subject/ - Screen Daily: ‘Film About A Father Who’ – Sheffield Doc/Fest Review, June 15, 2020

https://www.screendaily.com/reviews/film-about-a-father-who-sheffield-doc/fest-review/5150622.article - Il Manifesto: “A Dialogue of Images That Question Our Certainties” – Interview with Lynne Sachs, June 11, 2020

https://ilmanifesto.it/lynne-sachs-dialogo-di-immagini/?fbclid=IwAR22UJ0x7YZSjIpXk-7VWUyNgxl-e-y80MDZFupanICvMgjgV6aASy8TorA - Modern Times Review: «A new relationship to language and listening in cinema»: Lynne Sachs on her Sheffield Doc/Fest Retrospective,” Interview with Lauren Wissot June 17, 2020

https://www.moderntimes.review/lynne-sachs-on-sheffield-doc-fest-retrospective/ - Ubiquarian: “The Process is the Practice: Prolific and poetic, experimental and documentary filmmaker, Lynne Sachs, lights up this year’s online edition of Sheffield Doc|Fest with a mini-retrospective, annotated lecture and her new feature, Film About a Father Who (2020)” by Tara Judah, June 21, 2020

http://ubiquarian.net/2020/06/the-process-is-the-practice/ - Film International: Review of “Film About a Father Who” by David Finkelstein, July 5, 2020. http://filmint.nu/film-scratches-july-2020/

- In Their Own League, Five stars (out of 5) review “Film About a Father Who -Poetic, impactful and moving journeys into unique worlds which are rarely captured on-screen” by Bianca Garner, July 13, 2020. https://intheirownleague.com/2020/07/12/sheffield-doc-fest-exclusive-review-film-about-a-father-who/

- Docs in Orbit: “Master Edition: In Conversation with Lynne Sachs” Podcast Pt. 1 and Pt. 2, August 2020.

- Pt. 1- Lynne Sachs speaks about how feminist film theory has shaped her work and her approach to experimental filmmaking

- Pt. 2 – We discuss her latest feature-length documentary film, Film About a Father Who.https://www.docsinorbit.com/masters-edition-in-conversation-with-lynne-sachs

- DocAviv Documentary Festival of Tel Aviv: From the Outside In: Investigation as a Language in the Films of Lynne Sachs, Two Film Program curated by Dr. Laliv Malemed – Overview, Sept. 2020. https://www.docaviv.co.il/2020-en/lynne-sachs/ ; Film About a Father Who – https://www.docaviv.co.il/2020-en/films/film-about-a-father-who/, States of UnBelonging – https://www.docaviv.co.il/2020-en/films/states-of-unbelonging/

- Ynet: Israel’s most comprehensive, authoritative daily source in English for breaking news and current events, “I Watched Rabin’s Funeral, I Named My Daughter Noa – Interview with Lynne Sachs” by Amir Bogen, Sept. 8, 2020.

https://www.ynet.co.il/entertainment/article/B1TCDpmmP - “The Artful, Experimental and Brilliant Study of a Promiscuous Father Headlining Sheffield Autumn Programme” by Benjamin Hollis, Oct. 2, 2020

- https://documentaryweekly.com/home/2020/10/2/the-artful-experimental-and-brilliant-study-of-a-promiscuous-father-headlining-sheffields-autumn-programme

- Memphis Flyer: “2020 Vision: Indie Memphis Film Festival Moves Outdoors and Online”, Festival Highlights, by Chris McCoy, Oct. 14, 2020.

https://www.memphisflyer.com/memphis/2020-vision-indie-memphis-film-festival-moves-outdoors-and-online/Content?oid=23975165 - VODzilla.com: The UK’s First Video on Demand Magazine: “Sheffield Doc/ Fest Film Review: Film About a Father Who”, by Laurence Boyce, Oct. 14, 2020. https://vodzilla.co/reviews/sheffield-doc-fest-film-review-film-about-a-father-who/

- Texte Zur Kunst: “Tactile Translations: Esther Buss on the Sheffield Doc/ Fest Lynne Sachs Film Exhibition”, Berlin, Germany, Oct. 16, 2020.

https://www.textezurkunst.de/articles/esther-buss-taktile-ubersetzungen/ - Brown University Alumni Journal: “Man in Focus” by Brent Lang Nov. – Dec., 2020.

https://www.brownalumnimagazine.com/articles/2020-10-23/a-man-in-focus - Rencontres Internationales du Documentaire Montreal: Interview with Lynne Sachs by Charlotte Selb, Nov. 18, 2020.

https://ridm.ca/en/events/entretien-lynne-sachs/?fbclid=IwAR2yXnSV68dMM3uhYA_WZ86Kngx-ti0cSDqTLSZi1slyyfOAoBQEwNTggMM - Business Doc Europe, Nick Cunningham’s interview with Lynne Sachs. “Doclisboa/MOMI New York: Daddy Dearest”, Dec. 15, 2020.

https://businessdoceurope.com/doclisboa-momi-new-york-daddy-dearest/ - Memphis Flyer “2020 on Screen: The Best and Worst of Film and TV: Film About a Father Who Best Documentary” by Chris McCoy, Dec. 23, 2020.

https://www.memphisflyer.com/memphis/2020-on-screen-the-best-and-worst-of-film-and-tv/Content?oid=24444547 - Plotaholics: “Go Indie Now Presents TOP INDIE FILMS OF 2020, PART 2: FILMS 10-6” by Joe Compton, Jan. 6, 2021.

https://plotaholics.com/2021/01/06/goindienow-presents-top-indie-films-of-2020-part-2-films-10-6/ - Alliance of Women Film Journalists: “Film About a Father Who Examines a Problematic Relationship.” Positive review of FILM ABOUT A FATHER WHO by Diane Carson. Jan. 8, 2021.

https://awfj.org/blog/2021/01/08/film-about-a-father-who-review-by-diane-carson/ - Slant Magazine: ”Film About a Father Who Walks Down a Recorded Memory Lane” Three stars (out of 4) review by Pat Brown, Jan. 10, 2021

https://www.slantmagazine.com/film/review-film-about-a-father-who-walks-down-a-recorded-memory-lane/ - WBAI-FM: “Cat Radio Cafe: Filmmaker and Feminist Lynne Sachs.” Hosted by Janet Coleman, January 11, 2021.

https://www.wbai.org/upcoming-program/?id=2629 - Unseen Films: “Film About a Father Who Opens Friday” by Steve Kopian, January 11, 2021.

http://www.unseenfilms.net/2021/01/film-about-father-who-opens-friday.html - (IDA) or Documentary.org: “Screen Time: Week of January 11, 2021” by Tom White, January 11, 2021.

https://www.documentary.org/blog/screen-time-week-january-11-2021 - The Flaherty: “January 2021 Newsletter- Flaherty CoPresentation With the Museum of the Moving Image,” January 2021.

https://theflaherty.org/news/flaherty-january-2021-newsletter - Reverse Shot: “Lynne Sachs Interview” by Chris Shields, January 12, 2021.

http://www.reverseshot.org/interviews/entry/2749/lynne_sachs_interview - E. Nina Rothe: ““Lynne Sachs: Between Thought and Expression” and why you cannot miss her MoMI retrospective” by E Nina Rothe, January 12, 2021.

https://www.eninarothe.com/faces/2021/1/6/lynne-sachs-between-thought-and-expression-and-why-you-cannot-miss-her-momi-retrospective - Eye for Film: “Film About a Father Who – Review“ by Amber Wilkinson, January 12, 2021.

https://www.eyeforfilm.co.uk/review/film-about-a-father-who-2020-film-review-by-amber-wilkinson - Screen Slate: “Lynne Sachs Interview: Film About a Father Who,” by Conor Williams, January 13, 2021.

https://www.screenslate.com/articles/469?mc_cid=03fa516ae8&mc_eid=7a575b7f3b - This Week in New York: “Lynne Sachs: Between Thought and Expression,” January 13, 2021.

http://twi-ny.com/blog/2021/01/13/lynne-sachs-between-thought-and-expression/ - Cine-Journal: “Interview with a filmmaker who…” by George Robinson, January 13, 2021.

https://cine-journal.blogspot.com/2021/01/interview-with-filmmaker-who.html - The Film Experience: “Doc Corner: Lynne Sachs’ ‘Film About a Father Who’” by Glenn Dunks, January 13, 2021.

http://thefilmexperience.net/blog/2021/1/13/doc-corner-lynne-sachs-film-about-a-father-who.html - Nashville Scene: “With Her Latest, Lynne Sachs Profiles Her Father — and Her Complicated Family” by Craig D. Lindsey, January 13, 2021

https://www.nashvillescene.com/arts-culture/film/article/21145389/film-about-a-father-who - The Wrap: “‘Film About a Father Who’ Film Review: Lynne Sachs Tries to Understand Her Dad in Thorny Doc” by Steve Pond, January 13, 2021.

https://www.thewrap.com/film-about-a-father-who-film-review-lynne-sachs-tries-to-understand-her-dad-in-thorny-doc/ - NYTimes: “Film About a Father Who Review: Family Secrets by Omission” by Ben Kenigsberg, January 14, 2021.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/14/movies/film-about-a-father-who-review.html?smid=tw-nytimesarts&smtyp=cur - MUBI Notebooks: “Lynne Sachs: Between Thought and Expression” by Kat Sachs, January 14, 2021.

https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/lynne-sachs-between-thought-and-expression - Criterion Collection – The Daily: “Perspectives on Lynne Sachs,” by David Hudson, January 14, 2021.

https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/7245-perspectives-on-lynne-sachs - Gay City News: “‘Film About a Father Who’ Explores Ira Sachs, Sr.’s Turbulent Life” by Steve Erickson, January 14, 2021.

https://www.gaycitynews.com/film-about-a-father-who-explores-ira-sachs-sr-s-turbulent-life/ - Roger Ebert: “”Film About a Father Who – Review” by Matt Zoller Seitz, January 15, 2021.

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/film-about-a-father-who-movie-review-2021 - Trust Movies: “‘Lynne Sachs’ ‘Film About a Father Who’ breaks new ground in the “family” documentary department” by James Van Maanen, January 15, 2021.

https://trustmovies.blogspot.com/2021/01/lynne-sachs-film-about-father-who.html - LA Times: “‘Review: Nine children with six women? ‘Film About a Father Who’ untangles director’s family tree” by Robert Abele, January 15, 2021.

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/movies/story/2021-01-15/film-about-a-father-who-review - The Film Stage: “New To Streaming…” by Jordan Raup, January 15, 2021.

https://thefilmstage.com/new-to-streaming-promising-young-woman-mlk-fbi-news-of-the-world-one-night-in-miami-more/ - What (not) to Doc: “In Virtual Release: FILM ABOUT A FATHER WHO,” by Basil Tsiokos, January 15, 2021.

https://whatnottodoc.com/2021/01/15/in-virtual-release-film-about-a-father-who/ - Docs in Orbit: “Lynne Sachs Retrospective t the Museum of the Moving Image” Hosted by Christina Zachariades, January 15, 2021.

https://www.docsinorbit.com/lynne-sachs?fbclid=IwAR0hyok8rheiIKlTIdFNNvU5duab6NJ3fRsEgUoLziS5334hGq1vSxNjbaI - DocNYC: “Monday Memos” mentions FAAFW and Retrospective by Jordan M. Smith, January 18, 2021. https://mailchi.mp/docnyc.net/mondaymemo-2021-01-18?e=dfb43bb105

- Spectrum Culture: “Film About a Father Who Review,” by Joel Copling, January 19, 2021.

https://spectrumculture.com/2021/01/18/film-about-a-father-who-review/ - Cleveland.com: “Cinematheque hosting Zoom Q&A with Director Lynne Sachs regarding ‘Film About a Father Who’” by John Benson, January 20, 2021.

https://www.cleveland.com/entertainment/2021/01/cinematheque-hosting-zoom-qa-with-director-lynne-sachs-regarding-film-about-a-father-who.html - Hyperallergic: “30 Years of Offbeat Documentaries by Lynne Sachs” by Dan Schindel, January 21, 2021.

https://hyperallergic.com/615665/momi-lynne-sachs-retrospective/ - Letterboxd: “Andrew Wyatt Reviews FAAFW on Letterboxd” by Andrew Wyatt, January 21, 2021.

https://letterboxd.com/awyatt76/film/film-about-a-father-who/ - In Review Online: “Film About a Father Who | Lynne Sachs” by Nicholas Yap, January 21, 2021.

https://inreviewonline.com/2021/01/21/film-about-a-father-who/ - DeFacto Film Reviews: “Film About a Father Who” by Robert Joseph Butler, January 27, 2021.

http://defactofilmreviews.com/film-about-a-fatherwho/ - Filmmakers’ Cooperative: “Panel Discussion with MM Serra, Jack Waters, and Bradley Eros,” January 27, 2021.

https://film-makerscoop.com/screenings/lynne-sachs-zoom-panel-discussion - [refedine] magazine Reviews: “Film About a Father Who” by Alison Smith, January 30, 2021.

https://redefinemag.net/2021/film-about-a-father-who-lynne-sachs-film-review/ - The Flaherty: “February 2021 Newsletter- Dispatch – ‘An Evening With the Sachs Family” by Anto Astudillo February 2021.

https://theflaherty.org/news/flaherty-2021-newsletter-february - Canada’s National Observer: “Reviewing a gem from the Victoria Film Festival….” By Volkmar Richter, February 5, 2021.

https://www.nationalobserver.com/2021/02/05/reviews/reviewing-gem-victoria-film-festival-couples-loud-and-long-night-and - The Eagle: “‘Film About a Father Who’ candidly explores kinship and neglect” By Volkmar Richter, February 5, 2021.

https://www.theeagleonline.com/blog/silver-screen/2021/02/film-about-a-father-who-candidly-explores-kinship-and-neglect - Film Dienst: “First person #3: A conversation with filmmaker Lynne Sachs” by Esther Buss, February 6, 2021.

https://www.filmdienst.de/artikel/46116/kracauer-blog-lynne-sachs-interview - 48 Hills: “Screen Grabs: The outlaw sounds of youth” by Dennis Harvey, February 8, 2021.

https://48hills.org/2021/02/screen-grabs-the-outlaw-sounds-of-youth/ - Cine-File Selects: “Film About a Father Who” by Kathleen Sachs, February 11, 2021.

https://www.cinefile.info/ - Cineaste: “Review of Film About a Father Who”, Feb. 2021.

https://www.cineaste.com/spring2021/film-about-a-father-who

Rotten Tomatoes: https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/film_about_a_father_who

IMDB – https://www.imdb.com/title/tt11600484/?ref_=ttexrv_exrv_tt

Credits

Featuring Ira Sachs Sr. with Lynne Sachs, Dana Sachs, Ira Sachs, Beth Evans, Evan Sachs, Adam Sachs, Annabelle Sachs, Julia Buchwald, and Madison Geist

Editor – Rebecca Shapass

Music – Stephen Vitiello

Produced with the support of: New York Foundation for the Arts Artist Fellowship, 2018 and Yaddo Artist Residency, 2019