June 1 2020

Announcing 2020 filmmakers’ spotlights and our retrospective

Today Sheffield Doc/Fest begins its festival with the international premiere of my feature Film About a Father Who along with a “spotlight” on six of my films.

“Two filmmakers have inspired a special focus: Simplice Ganou and Lynne Sachs” From very different regions of the globe (Burkina Faso and USA), with very different ways of filming and telling stories, both are filmmakers obsessed with the possibility of encountering the other, of building bonds with other humans through their camera, and translating that into cinematic beauty.”

“Drawing on her vast body of works from the past 30 years, we will present a curated selection of films by Lynne Sachs, focusing on the notion of translation as a practice of encountering others and reshaping and reinterpreting filmic language. This focus will be part of the online Ghosts & Apparitions film strand.”

In the lead up to revealing our full official selection for 2020 on 8 June, we would like to announce:

- the theme of our annual retrospective: Reimagining the Land, curated by Christopher Small.

- and three special focuses:

- a screening in tribute to the late French West Indies film pioneer Sarah Maldoror;

- a focus on American artist Lynne Sachs;

- a focus on Burkina Faso filmmaker Simplice Ganou.

Focus on Lynne Sachs

Drawing on her vast body of works from the past 30 years, we will present a curated selection of films by Lynne Sachs, focusing on the notion of translation as a practice of encountering others and reshaping and reinterpreting filmic language. This focus will be part of the online Ghosts & Apparitions film strand.

Five Lynne Sachs films ranging from 1994 – 2018 – mostly involving creative collaboration with others – will feature as part of our online programme from 10 June.

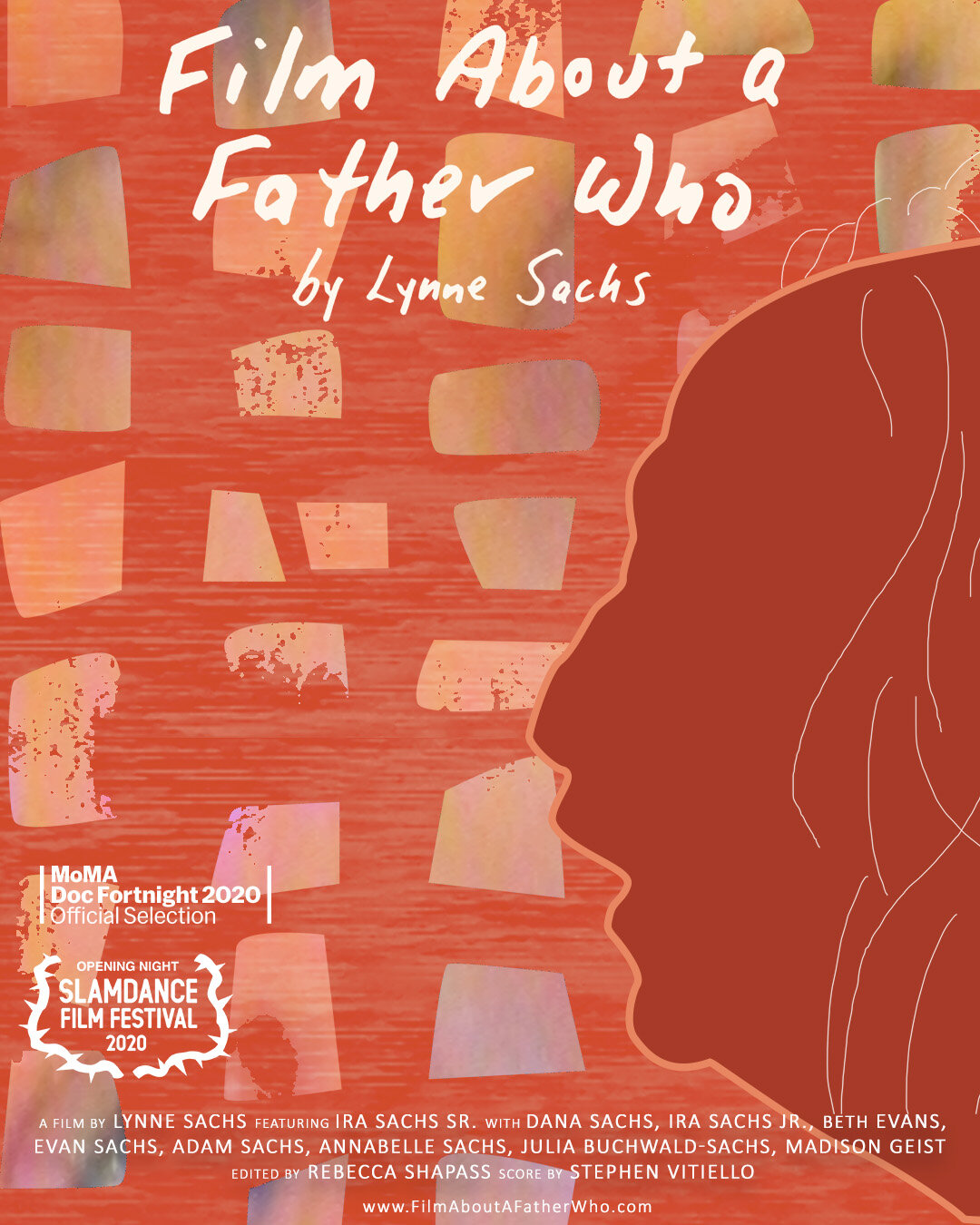

Her latest film, Film About a Father Who, offers a complex portrait of Ira Sachs Sr., a bon vivant and pioneering businessman from Park City, shot over a period of 35 years, and will make its International Premiere in Sheffield in October, and following that, online, as part of Into The World Film Strand.

Together with the focus, we will present Sachs’ video lecture My Body, Your Body, Our Bodies: Somatic Cinema at Home and in the World, a fascinating journey through her themes and work.

Lynne Sachs focus, in Ghosts & Apparitions online:

Drawing on her vast body of works from over the past 30 years, we will present a curated selection of films by Lynne Sachs, focusing on the notion of translation as a practice of encountering others and reshaping and reinterpreting filmic language. Tensions arise from the filmmaker’s memories of Vietnam as a tragic place of war in Which Way Is East…; The Last Happy Day is a portrait of a man who translated “Winnie the Pooh” into Latin and reconstructed the remains of American soldiers; Your Day Is My Night tells of places in New York inhabited by immigrant workers and shaped by their lives and stories; the translation of Barbara Hammer’s images and sounds on a deserted landscape become a poem for her deceased friend in A Month of Single Frames. If translation can be considered the job of filmmaking, these works become a poetic and political tool for widening our view of the world and touching on its complexity, rendering it intimate and available for thought. Between them – Theatre, performance, music and an extremely sensitive and tender camera – compose a body of work that becomes more relevant each day.

WHICH WAY IS EAST: NOTEBOOKS FROM VIETNAM

Lynne Sachs (in collaboration with Dana Sachs), USA, 1994, 33 min

“A frog that sits at the bottom of a well thinks that the whole sky is only as big as the lid of a pot.”

Two American sisters travel from Ho Chi Minh City to Hanoi, followed by their own ghosts and those of local memories. On their way, they meet a country and its richness – strangers, translations, parables and stories, in a complex landscape. History is put into perspective, as each conversation becomes a true encounter: uncountable possible words to translate what we see and what we hear. The Vietnam they knew from TV is only a tiny part of this world to which they now decide to pay attention.

THE LAST HAPPY DAY

Lynne Sachs, USA, 2009, 37 min

A portrait of Sandor (Alexander) Lenard, a Hungarian medical doctor and a distant cousin of Sachs. In 1938 Lenard, a writer with a Jewish background, fled the Nazis to Rome. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. Army Graves Registration Service hired him to reconstruct the bones of dead American soldiers. Eventually he found himself in Brazil where he translated “Winnie the Pooh” into Latin, an eccentric task that catapulted him to brief world-wide fame. Personal letters, abstracted war imagery, home movies, interviews, and a children’s performance create an intimate meditation on the destructive power of war.

YOUR DAY IS MY NIGHT

Lynne Sachs, USA, 2013, 64 min

Since the early days of New York’s Lower East Side tenement houses, working class people have shared beds, making such spaces a fundamental part of immigrant life. A “shift-bed” is an actual bed that is shared by people who are neither in the same family nor in a relationship. It’s an economic necessity brought on by the challenges of urban existence. Such a bed can become a remarkable catalyst for storytelling as absolute strangers become de facto confidants. As the bed transforms into a stage, the film reveals the collective history of Chinese immigrants in the USA, a story not often documented.

THE WASHING SOCIETY

Lynne Sachs and Lizzie Olesker, USA, 2018, 44 min

When you drop off a bag of dirty laundry, who’s doing the washing and folding? The Washing Society brings us into New York City laundromats and the experiences of the people who work there. With a title inspired by the 1881 organization of African-American laundresses, The Washing Society investigates the intersection of history, underpaid work, immigration, and the sheer math of doing laundry. Dirt, skin, lint, stains, money, and time are thematically interwoven into the very fabric of the film, through interviews and observational moments. With original music by sound artist Stephen Vitiello.

A MONTH OF SINGLE FRAMES

Lynne Sachs, made with and for Barbara Hammer, USA, 2019, 14 min

In 1998, filmmaker Barbara Hammer had a one-month artist residency in the C Scape Duneshak which is run by the Provincetown Community Compact in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. While there, she shot 16mm film with her Beaulieu camera, recorded sounds with her cassette recorder and kept a journal. In 2018, Barbara began her own process of dying by revisiting her personal archive. She gave all of her Duneshack images, sounds and writing to filmmaker Lynne Sachs and invited her to make a film with the material.

International Premiere of Lynne Sachs’s latest film, as part of Into The World screenings in October:

FILM ABOUT A FATHER WHO

Lynne Sachs, USA, 2020, 74 min

International Premiere

Over a period of 35 years, Sachs shot varied footage of her father, Ira Sachs Sr., a bon vivant and pioneering Utah businessman. This is her attempt to understand the web that connects child to parent and sister to sibling. With a nod to the Cubist renderings of a face, Sachs’ cinematic exploration offers simultaneous, sometimes contradictory, views of one seemingly unknowable man who is publicly the uninhibited center of the frame yet privately ensconced in secrets. Sachs as a daughter discovers more about her father than she had ever hoped to reveal.