Seannon Nichols

Final Paper/Exam

COM 450 Experimental Cinema: History and Theory

November 18, 2014

Lynne Sachs: Prescribing the Cure to Existential Crises by Utilizing ‘Experience Cinema’ as a means to partake in, and showcase organically produced affirming moments in nature through Drift and Bough (2014), Georgic for a Forgotten Planet (2008), Photograph of the Wind (2001), and Tornado (2001).

Viewing what one wishes to see or thinks about in their minds eye is something that was once only possible in dreams. However dreams were made into realities when the camera was invented. Since the first camera was used, it is clear that representations of ideas can be shared and experienced by anyone who seeks them. The people behind these ideas are the filmmakers. Filmmakers are a sum of their experiences. Experiences shape how they do things, how they think, what they feel, and why they are here. The difference between filmmakers and every one else is that they chose to represent all these things in their work. They chose to share the sum of their parts.

Depending on the filmmaker there usually are different parts, so the sum doesn’t always add up to the same thing. This is especially true in avant-garde or experimental filmmakers. Every avant-grade filmmaker has a unique way of expressing themselves. Avant-garde by definition means not of the norm, before anything ordinary they exist.

The one who speaks to the tortured soul in all of us is Lynne Sachs. Sachs is a self defined experimental filmmaker. Sachs, born August 10th, 1961, originally from Tennessee, now she works primarily out of New York. She is a mom and filmmaker, a lot of the time combining the two in her works. When asked why she used so many different kinds of art in her films and if thats why she considered herself experimental she responded in saying “Honestly, I sometimes feel like a scientist working with materials that are simultaneously familiar and exotic. When I juxtaposed a home movie of my fourth birthday with an image of a black widow spider in my film “The House of Science”, I was experimenting with meaning, making suggestions about the connections between childhood and fear. I didn’t know if my “experiment” worked until I activated it with an audience. I’ve never been attracted to the kind of filmmaking that necessitates that you follow a formula for writing a script. The idea that there is a software template, for example, that screenwriters use to create a narrative film disturbs me to my very core. Each time I come up with an idea for a new film, I have to try out new ways of using a camera, which might seem as basic as it gets. I play with the technology as much as a feature filmmaker plays with her story. In an experimental film, the form and the content are essentially strangers who eventually will become the dearest of friends. Finding the chemistry for this new “relationship” pushes the experimental filmmaker to invent, play, take risks, fail and get right back up again.”

Her work is her life and in order to understand her work you need to understand her influences. In an interview I conducted with Sachs she expressed to me that her style and influences come from a plethora of directors such as “Chris Marker, Chantal Ackerman, Bruce Conner, Stan Brakhage, Haron Farocki, Holis Frampton, and so many others!” She also expressed to me upon my probing that Su Friedrich is one of her many influences. I had noticed a similarity in style with them when I had made the comparison of the two in my own critical review. Then subsequently, when asked wether I was correct in the similarities she responded by telling me “Su’s early films were extremely influential to me. Her oneiric “Gently Down the Stream” seemed to have been spit right out of a dream she had the night before she made the film. When I saw that film, I was awed by the closeness she had to her unconscious. Later, I saw “Sink or Swim” and was enthralled with her ability to tell such an intimate story about her relationship to her father while she was growing up. Throughout her career, there has always been an implicit confidence in the ability of women to find their way in the world and to express this journey from a specifically female perspective. This is in and of itself a political position that resonates with me. Both of us often intertwine autobiography with observations of the world around us.” Her obvious pull towards feministic ideals along with her desire to tell intimate stories about the relationships between objects and people and between people themselves came from all these influences. The focus and connection I’m demonstrating will be Stan Brakhage’s penetration through her work.

It is said that “Brakhage’s work… required nothing less than a radical revision of the conditions of cinematic representation and the rejection, in practice, of its codes… which entailed both a redefinition of the space of cinematic representation, and the institution, through speed and validity of editing… and bodily movement traced by a handheld camera. (Michelson, pp. 113)” He revolutionized what filmmakers could do with cameras and subscribed to no rules and regulations. His painting directly on celluloid and scratching on celluloid (Sitney), created a whole new way to view film and relay messages which opened a completely new door for linguistics. Many filmmakers following him chose to walk through that door, including Su Friedrich. Like Friedrich and many other using linguistics in film had become a popular fashion and Sachs jumped on that train as well. Her love of the written word was present before her love of filmmaking, especially when it comes to poetry. In our interview she mentioned “When I decided to become a filmmaker, I never had to abandon my poetry writing…” It is vital to her artistic expression and to her representation of relationships and their meanings.

Lynne Sachs filmography as a whole stretches far and wide across genres and themes. Some themes that seem particularly important and relevant within her works are nature, relationships, and organically produced joy. Thus comes my interpretations of some of her best works. Lynne Sachs, contemporary avant-garde filmmaker, showcases and manufactures ‘experience cinema’ by showing atmospheres where audiences are saturated in overwhelming organic sensations, thereby exploring existentialism as it as a means to deter existential crises or as it applies to every day life, which can be seen in her films Drift and Bough (2014), Georgic for a Forgotten Planet (2008), Photograph of the Wind (2001), and Tornado (2001).

In order to fully understand the assertion of Sachs’ films as an aide to existentialism through ‘experience cinema’ I must explain those two concepts. To start, existentialism. Existentialism as most clearly defined, in the way that I am referring to it, is a philosophical theory or approach that emphasizes the existence of the individual person as a free and responsible agent determining their own development through acts of will. Earlier it is said that Sachs films can be used as a way to deter existential crises. Now that we know what existentialism is we need to determine what one does when they are suffering from a crisis of the theory. Normally that type of crisis is defined as one where an individual may waver on their meaning in the world, wether their particular life serves any purpose, or makes any true impact on this existence.

Next, one must understand the term “experience cinema.” “Experience Cinema” is a kind of cinema that I was seeing in some filmmakers pieces but had no term for it specifically. It is something that is not present in every film and that all filmmakers cannot achieve. I do believe it is possible to try and write a scene that is considered experience cinema but for the most part the cinematographer or directors needs to find or produce it. The clearest way it can be explained is something that happens in a scene or throughout a film, when your whole body becomes enraptured with a character, a setting, a sensation, a particular visual, because they touch upon everyone of your senses. Sachs’ films, the ones I chose in particular demonstrate this with every ticking second. She understands how to perfect an image with a camera and incorporate different stylistic types of art to make a perfect recipe of cinematic sensations that occupy the viewer so that it becomes four dimensional. Our brains make it real. I will start explaining more clearly what I mean with the aforementioned films by Lynne Sachs, in order to supply sufficient evidence that experimental cinema demonstrates itself as proof that we are here and by enjoying life’s organically produced moments there is no need to have existential crises.

Drift and Bough (2014) was made by Sachs in central park in New York City during a particularly aggressive snowstorm. This black and white film shot in super 8mm is a six minute film that opens on a partially covered empire state building and sweeps down to the ground, as if to follow the elegantly aggressive white snow falling to the park. The harsh winter winds blow through the trees and covers the rambles. It’s covering the people and the benches, covering whoever and wherever it wants, even the ducks trying to make their way through the frozen pond. It is clear it is snowing heavily and fast and you can experience how cold it is when the frozen people, all bundled up in their winter’s best, waddle by. The branches of the trees hang low from the weight of the snow and they struggle against the winds, as do the birds who group together trying to avoid this storm that ravages around them. When the storm finally calms we see a child heading up a hill with a sled enjoying the calm after the storm. A dog joyously celebrates his new snow covered park along with a people in a bike carriage enjoying the fresh fallen snow. As you can see by the representations of forceful nature and the pure joy experienced by its surroundings and individuals who realize that the anger of mother nature calmed to beauty, they are really living. When the film is played backwards in the middle after the storm has stopped all the previous images of the cold ducks and the snow heavy trees take on a different connotation. One that appreciates winter and what we have. That togetherness and the simple beauty of snow is a reason to be glad that we are here. Experience cinema has given the viewer harsh cold, relief, joy, Childish excitement, beauty, purity, and music that stirs the soul and looked to stir the snow.

Georgic for a Forgotten Planet (2008) is a film about wildlife in central park. When interviewing Sachs she told me in this film “I love working with plants or finding the biomorphic in inanimate things. Living in New York City, I probably don’t get enough pure living, so I try to make up for that by weaving in images of gardens or trees or water in my films. “Georgic for a Forgotten Planet” was shot in community gardens around the city and the title comes from Virgil’s Georgics, which were poems to agricultural written in 29 B.C.E.” The interweaving in the film with this eerily centric music accompanied by street noises and organic plant life and human interaction, including Sachs change of camera lens, makes this whole piece feel raw and gentle. The scene where she shoots up at the dandelions and weeds and accompanied by trucks and airplanes over head makes it clear that these simple plant pleasures are being missed by the busy world around it. She demonstrates this again by the editing of one shot during the busy street over the ignored plant life. Her homage to joyous organic moments, the bee pollenating the plant while a child plays and then the coming of water, all rounds out they joy one could find in life is one only appreciated it. There would be no need to internalize frustration about why we are here if you appreciated the joy of whats in front of you. The way she places the camera in nature makes one reflect back to brakhage and his many treks through the colorado forest. “I have always loved the way Brakhage creates abstract images from the flora and fauna that surrounded him in Colorado” Sachs says. Her inspiration to capture and influences from his work is apparent. When Sachs wrote a paper about Brakhage and his work on Window Baby Water Moving she comments that “Brakhage’s images have clearly touched me personally, aesthetically, and intellectually as a mother and as a maker of experimental films (Sachs, pp. 194).” Clearly his influence reaches far and deep and those struggle to appreciate the world and their purpose in it have Sachs and Brakhage to thank for the release they might find in their works.

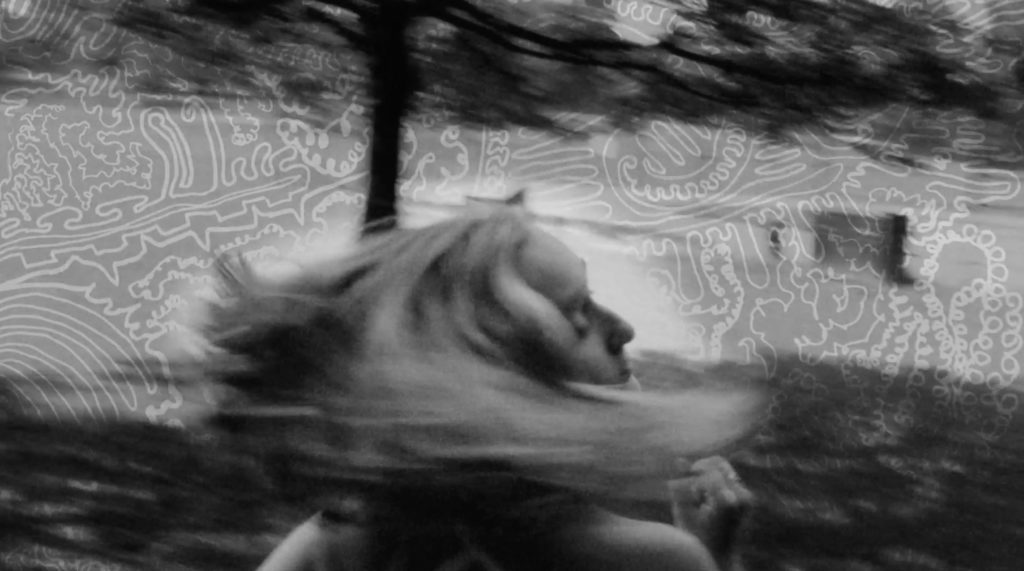

Next is Photograph of the Wind andTornado (2001). Photograph of the Wind is a work in black and white that follows Sachs’ daughter Maya, named after Maya Deren, spinning around her running in a circle creating wind in her hair. In the description of the video Sachs said “ As I watch her growing up, spinning like a top around me, I realize that her childhood is not something I can grasp but rather (like the wind) something I feel tenderly brushing across my cheek.” Clearly speaking in terms she was unfamiliar with at the time, this is exactly experimental cinema doing its job. Feeling the wind whip through her daughters hair, and sensing the turn of a top as you spin round and round. Sachs’ herself had a realization of existentialism. She was here forever trying to hold on to the childhood of her daughter finally realizing like the wind its something she cannot grasp but has to appreciate.

In Tornado (2001) Lynne shows the charred remains of papers that were destroyed after September 11th, and twin towers were crashed into. It coincides with a poem about tornadoes and how they destroy everything in its path. What makes this film so important, and in my opinion the best of her experience cinema films is the hands that hold the charred and ripped papers. They are wrinkled and smooth and you can hear them rustling with themselves and scratching along the paper, as if to say these pages may be broken but I still remain whole. These works are all representative or productions of experience cinema they make you feel and have reaffirmations of life. They affirm our existence they represent creation. Audience experience why they exist. They aide in those who question it.

These representations can be seen in popular cinema as well. One of the films I find most representation of experimental cinema and existentialism, which in hollywood cinema seems to be produced in americana crises, is American Beauty. This film tells the story of Lester Burnham who lived his suburban life in a daze and one day is awoken to find he hadn’t been experiencing life at all. Some might say he had a mid-life crisis. I believe he had a mid-life awakening and the way Sam Mendes represents this is through experience cinema. In particularly with the protagonist, there is a scene where he is fantasizing about a teenage girl Angela, and he walks into a steam filled bathroom and you can feel his heart race, and the wet sticky steam of the bathroom and the softness of the rose petals that lay in the water on top of Angela. This erotic metamorphous from a non sensational life into a full on orgasm of sensational experiences shows his existential turmoil fading away with experience cinema. Another example in the film of experience cinema being used to explore existentialism is the scene where Ricky shows Jane his video of the most beautiful thing he’s ever shot, a plastic bag blowing in the wind. This video showcases how this epithelial object danced with the wind and no one appreciated the simplistic beauty but Ricky. He saw the beauty in real life. He was the only one of them that was truly living. Ricky woke everyone up. He was the savior of suburbia.

Another few pop culture films that deal with existentialism outright are Groundhog’s Day, when a weather man must relive groundhog’s day over and over and over again until he is living a true and happy life. Another few are The Truman Show, I Heart the Huckabees and Fight Club. Now Fight Club more so represents than some of the others because the main character Tyler Durdin is a projection of Edward Norton’s subconscious to preform his desired actions. His life was already in an existential crisis. It takes him the whole movie to figure it out, but he is having one nonetheless. These subsequent films use different idioms to resurrect existential crises but they serve the purpose to show that this genre of self doubt is one that is still relevant even in fields that aren’t experimental.

In conclusion, Lynne Sachs as an experimental filmmaker is one to be admired. Her films do more than just entertain, they reach through the screen and enrapture your senses with experimental cinema. Wether she is citing beautiful poetry or overlaying bohemian experimental music over her images, you feel their power. They affirm why we are here. What their is on this earth for individuals to appreciate. We do not need to feel lost or purposeless, there is joy everywhere. Every organism matters. Lynne Sachs shows us that.

Bibliography

Deutsch, J. (2004). Maya Deren and the American Avant-garde. American Studies In ternational, 42(1), 132-133. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.esearch.ut.edudocview/ 197130140accountid=1476

Drift and Bough. Dir. Lynne Sachs. 2014. DVD.

Fincher, David, Arnon Milchan, Jim Uhls, Art Linson, Ceán Chaffin, Ross G. Bell, Brad Pitt, Edward Norton, Carter H. Bonham, Loaf Meat, Jared Leto, Zach Grenier, Holt McCallany, Eion Bailey, Michael Kaplan, James Haygood, Alex McDowell, and Jeff Cronenweth. Fight Club. Beverly Hills, Calif: Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2002.

Georgic for a Forgotten Planet. Dir. Lynne Sachs. 2008. DVD.

Mendes, Sam, Alan Ball, Bruce Cohen, Dan Jinks, Kevin Spacey, Annette Bening, Thora Birch, Mena Suvari, Wes Bent ley, and Chris Cooper. American Beauty. Universal City, CA: DreamWorks Home Entertainment, 2000.

Michelson, Annette. “Stan Brakhage (1933-2003).” October 108 (2004): 112-115. Academic Search Complete. Web. 8 Dec. 2014.

Niccol, Andrew, and Peter Weir. The Truman Show. Hollywood, CA: Paramount Pictures, 1999.

Photograph of the Wind. Dir. Lynne Sachs. 2001. DVD.

Pierson, Michele. “Avant-Garde Re-Enactment: World Mirror Cinema,Decasia, and The Heart of the World.” Cinema Journal 49.1 (2009):1-19. JSTOR. Web. 27 Oct. 2014. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/25619742>.

Rabinowitz, Paula. “Medium Uncool: Women Shoot Back; Feminism, Film and 1968 — A Curious Documentary.” Science & Society 65.1 (2001):72-98. JSTOR. Web. 27 Oct. 2014. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/40403885>.

Ramis, Harold, Bill Murray, Andie MacDowell, Chris Elliott, Stephen Tobolowsky, and Brian Doyle-Murray. Groundhog Day. Burbank, Calif: Columbia TriStar Home Video, 1993.

Russell, David O, Jeff Baena, Gregory Goodman, Scott Rudin, Dustin Hoffman, Lily Tomlin, Jason Schwartzman, Isabelle Huppert, Jude Law, Peter Deming, and Jon Brion. I [heart] Huckabees. Los Angeles, CA: 20th Century Fox Home Enter tainment, 2004

Sachs, L. (2007). Thoughts on birth and brakhage. Camera Obscu ra, (64)194-196. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.esearch.ut.edu/docview/217539662?accountid=14762

Tornado. Dir. Lynne Sachs. 2001.

___________________________________________________________________________

FULL INTERVIEW

1. What influences, as far as directors, do you have when you do your work?

I have been inspired by Chris Marker, Chantal Ackerman, Bruce Conner, Stan Brakhage, Haron Farocki, Holis Frampton, and so many others!

2. You tend to use many different forms of art in your filmmaking, like collage, painting, and layered sound deign, in your works, why did you decide to use all these forms instead of just shooting? Is that what experimental is to you?

For me, each film needs to search for its own language of expression, and this creative journey is never mapped out ahead of time. I love using my camera, of course, but I also find the dialogue between the moving image and other artistic forms to be quite unpredictable and, therefore exciting. When I decided to become a filmmaker, I never had to abandon my poetry writing or my love of collage and painting. My work in sound came more recently, as I discovered that the aural dimension invited audiences to participate more freely with the cinematic moment.

- If not what about your work defines it as experimental cinema?

I really love that you are curious about the word experimental. Honestly, I sometimes feel like a scientist working with materials that are simultaneously familiar and exotic. When I juxtaposed a home movie of my fourth birthday with an image of a black widow spider in my film “The House of Science”, I was experimenting with meaning, making suggestions about the connections between childhood and fear. I didn’t know if my “experiment” worked until I activated it with an audience. I’ve never been attracted to the kind of filmmaking that necessitates that you follow a formula for writing a script. The idea that there is a software template, for example, that screenwriters use to create a narrative film disturbs me to my very core. Each time I come up with an idea for a new film, I have to try out new ways of using a camera, which might seem as basic as it gets. I play with the technology as much as a feature filmmaker plays with her story. In an experimental film, the form and the content are essentially strangers who eventually will become the dearest of friends. Finding the chemistry for this new “relationship” pushes the experimental filmmaker to invent, play, take risks, fail and get right back up again.

4. One of the reason I like Su Friedrich’s work is because it uses narrative form and documentary form with interviews as well as makes commentary, you tend to use political issues to make social commentary like your recent work Your Day is My Night, but use the same kind of form. Is this what you’re really passionate about or what inspired you to do this work? Did Su Friedrich’s Style have any influence?

Su’s early films were extremely influential to me. Her oneiric “Gently Down the Stream” seemed to have been spit right out of a dream she had the night before she made the film. When I saw that film, I was awed by the closeness she had to her unconscious. Later, I saw “Sink or Swim” and was enthralled with her ability to tell such an intimate story about her relationship to her father while she was growing up. Throughout her career, there has always been an implicit confidence in the ability of women to find their way in the world and to express this journey from a specifically female perspective. This is in and of itself a political position that resonates with me. Both of us often intertwine autobiography with observations of the world around us.

5. Georgic for a Forgotten Planet, was inspired by poetry by relates heavily to nature, is nature something your passionate about, cause we see your connection to snow in Drift and Bough as well.

I love working with plants or finding the biomorphic in inanimate things. Living in New York City, I probably don’t get enough pure living, so I try to make up for that by weaving in images of gardens or trees or water in my films. “Georgic for a Forgotten Planet” was shot in community gardens around the city and the title comes from Virgils Georgics, which were poems to agricultural written in 29 B.C.E. I recently shot images of the People’s Climate March and hope to make a film with that material. “Drift and Bough” is simply a film I made in homage to Central Park, a natural wonder in the heart of the city where I find solace and joy. I shot the whole film during one snowstorm last winter.

6. Does this connection to nature come from a Stan Brakhage influence and his wonderings in Colorado.

Another great question, I have always loved the way Brakhage creates abstract images from the flora and fauna that surrounded him in Colorado, but the again he was also able to create exquisite beauty from a crystal ashtray in his “Text of Light” (1979).

7. The other works I’m examining are Tornado and Photograph of the Wind. I was wondering if you use these banal objects like your daughters hair and the charred papers to demonstrate beauty in meaningless articles?

Years ago I made two films about objects in our lives – “Still Life with Woman and Four Objects” (1986) and “Following the Object to Its Logical Beginning” (1987), so you are so right. I like to determine how we as humans engage with the things in our lives. In “Tornado” (2002), I am reflecting on the Twin Towers at the World Trade Center as objects that sadly became anthropomorphized when they fell and “died”. In “Photograph of Wind” (2001), I think a viewer does feel the swoosh of the wind through the watching of my daughter’s hair swirling around the camera. Your comparison of these two films which both integrate my daughters is very astute.

8. I’m terming this effect that you show in your films as “Experience Cinema” Cinema that you feel in every shot wether its the cold of snow or the wind of your spinning daughter. Is this something that you try to express when you make your films?

Wow! I love your naming of my films as “Experience Cinema”. I am honored by this very sensitive and perceptive observation and frankly I never could have come up with this myself. If making films gives me and hopefully you this shift of awareness, then I can be happy about my practice as an artist. While I love words dearly, this non-verbal level of communication is vital work.

9. Lastly, is there anything pertinent about the above films I’ve mentioned that you think I should know in regards to influence or things you were thinking during development?

You are a wonderfully insightful and original thinker. There is nothing I would add to this gift you have given me.