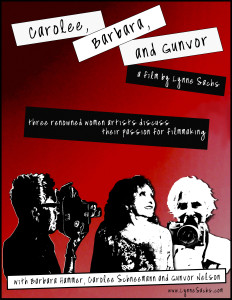

Carolee, Barbara & Gunvor

by Lynne Sachs

Super 8mm and 16mm film transferred to digital, 8 minutes, 2018

For inquiries about rentals or purchases please contact Canyon Cinema or the Film-makers’ Cooperative. And for international bookings, please contact Kino Rebelde.

Three renowned women artists discuss their passion for filmmaking.

From 2015 to 2017, Lynne visited with Carolee Schneemann, Barbara Hammer and Gunvor Nelson, three multi-faceted artists who have embraced the moving image throughout their lives. From Carolee’s 18th Century house in the woods of Upstate New York to Barbara’s West Village studio to Gunvor’s childhood village in Sweden, Lynne shoots film with each woman in the place where she finds grounding and spark.

Awards:

“Best of Festival” Onion City Experimental Film Festival, Chicago; Honorable Mention Jury Award, Festival de Curtas Belo Horizonte, Brazil; Honorable Mention, Woodstock Film Festival; Black Maria Film Festival Jury Award.

Screenings:

Premiere Documentary Fortnight, Museum of Modern Art, Feb. 20 – 26, 2018; Amherst College; Los Angeles Film Forum; Echo Park Film Center, Los Angeles; Other Cinema, San Francisco; Filmoteca Español, Madrid; “Xcèntric” Center of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona, Spain; Cosmic Ray Film Festival, Durham, NC; Oberhausen Film Festival, Germany; DocYard at the Brattle Theater, Boston; Athens Film and Video Festival (Ohio); Edinburgh Film Festival; Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center, Buffalo, NY; International Queer Film Festival, Hamburg, Germany; Pacific Film Archive/Berkeley Art Museum, Berkeley, California; Mill Valley Film Festival; Jhilava Film Festival, Czech Republic; Viennale, Vienna, Austria; Antimatter Media Arts Festival, Victoria, Canada; London Short Film Festival; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C; Queer Art Film, IFC Center, NY; Art of the Real, Lincoln Center; XPOSED International Queer Film Festival Berlin, Berlin; LUX & Club des Femmes present Evidentiary Bodies: Celebrating Barbara Hammer & Carolee Schneemann, London; Museo de Art Moderno Buenos Aires, Argentina; MUTA, International Audio Visual Appropriation Festival, Lima, Perú; Arteria, Cultural Information Centre, Zagreb, Croatia; Barbican, London; “Remake. Frankfurter Frauen Film Tage”, Kinothek Asta Nielsen Frankfurt, Germany, 2021; Festival International de Cine Contemporáno Camara Lucida; Cork International Film Festival, Ireland Artist Focus presented by Artist and Experimental Moving Image. DAFilms, Global Streaming; Carolee Schneemann “Body Politics” Film Series, The Barbican, London; Process Festival, Riga, Latvia, 2023; Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Rijeka, Croatia, 2023.

For inquiries about rentals or purchases please contact Canyon Cinema or the Film-makers’ Cooperative. And for international bookings, please contact Kino Rebelde.

Responses from Carolee and Barbara:

Hi dear Lynne, What a beautiful compilation…. I love my section and so appreciate the triple-visions within your camera life. It really is a lyric and incisive triple-portrait. I thank you so much for this clarity, visual richness. And I loved seeing Barbara with those old Bolex cameras! Your subtle inclusion of our personal surround has rhythm, shadow, light, momentum and quietude. How do we celebrate with you for this splendid work?

With love and admiration!

Carolee

——

Hi Lynne,

I finally had a chance to watch your lovely film! I was surprised at how energetically I performed for your camera, I was so happy when Gunvor finally spoke! She is as beautiful as ever. I’m honored Lynne, to be grouped with such strong and remarkable filmmakers.

Love,

Barbara

Artist Statement:

What is a body? What can a body do? How is a body rendered an object? And, how does this “object” have agency?

I believe these questions are at the root of a female guided exploration of art making. As a young filmmaker and student, I remember reading Laura Mulvey’s ground-breaking essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), in which she proposes that “sexual inequality is a controlling social force in the cinematic representations of the sexes; and that the male gaze is a social construct derived from the ideologies and discourses of patriarchy.” As I hold my camera and frame our world, I work extremely hard to keep her words in mind, knowing that gripping my own Bolex 16mm camera or writing my own scripts does not necessarily mean that I would produce images that came from my own experience as a woman. I needed to find a personal, somatic cinema that embraced a new physical relationship to this apparatus. It wasn’t just that I wanted to produce images that spoke to women’s lives, liberation, love, struggle, awareness or consciousness. When I first watched “Fuses” (1965) by Carolee Schneemann (https://vimeo.com/12606342), “Optic Nerve” (1985) by Barbara Hammer (https://vimeo.com/49508330) and “My Name is Oona” (1969) by Gunvor Nelson (https://vimeo.com/242768525) in the late 1980s, my own camerawork was catapulted into an expanded, self-aware, performative mode of working. Their radical, improvisational and totally physical cinematography pushed me and other women artists to dive deeply and fully into our bodies and ourselves.

Over the following decades, I became very close to all three women. They were dear friends, fellow artists, and mentors. Making “Carolee, Barbara, and Gunvor” is my gift to them, and theirs to me.

REVIEWS

Screen Slate – 2/22/18

https://www.screenslate.com/features/733

“Lynne Sachs’ Carolee, Barbara and Gunvor is an 8-minute triptych of brief encounters with Carolee Schneemann, Barbara Hammer, and Gunvor Nelson filmed at the artists’ homes or studios. Sachs has a really well-attuned photographic eye, and she captures the trio in a series of easygoing domestic situations. The three artists discuss their artistic lives, how they came into their practice, how their gender identities factor in, where their work comes from. It’s a simple premise with intimate results, especially good at giving a sense of the artists’ environments. ” (Tyler Maxin)

Village Voice – 2/16/18

by Ela Bittencourt

“I could make the inside of myself show on the outside,” Barbara Hammer says in Lynne Sachs’s documentary Carolee, Barbara & Gunvor (2018), explaining how a lighter movie camera, developed in the Sixties, helped her convey intimacy, and thus became a useful, malleable tool of expression. The short, in which Sachs pays a visit to pioneering women artists who used moving image in their practice — Hammer, Carolee Schneemann, Gunvor Nelson — will enjoy a weeklong run as part of “Doc Fortnight,” the Museum of Modern Art’s annual showcase dedicated to nonfiction film. (Ela Bittencourt)

Brooklyn Rail, 4/4/18

Review by Mark Block

https://brooklynrail.org/2018/04/artseen/JEFFREY-PERKINS-George

“A similarly brief and similarly enchanting encounter followed with the world premiere screening of Carolee, Barbara, and Gunvor, (2018) Lynne Sachs’s nine-minute cinematic collage exploring the distinctive styles and approaches of three artists. She delicately weaves them together by positioning them each in a place of familiarity and inner personal power to themselves and their work. Schneemann interacts with a film camera as a prop which becomes an inducer of memories in her Hudson Valley home; documentary maker Barbara Hammer moves around various sources of inspiration in her West Village studio and Gunvor Nelson shares glimpses of the village where she spent her childhood in Sweden. Each artist is gracefully and uniquely introduced via different relationships they have created with themselves, their environments, the filmmaker, and the audience.”

agnès films: Supporting Women and Feminist Filmmakers

4/5/2018

Review by Julia Casper Roth

http://agnesfilms.com/reviews/review-of-lynne-sachs-carolee-barbara-and-gunvor

It was deep into her artistic practice that Lynne Sachs shifted to a collaborative style of filmmaking. As she recounts on her website, Sachs was in the midst of recording a project when it struck her that those in front of the camera were performing. Aware that such hyperbolic displays might betray the authenticity of her subjects, Sachs invited the subjects to participate with her. No longer was her process about filming and being filmed. Rather, filmmaking became a joint effort that softened the camera as an intermediary and aloof barrier.

It’s this approach to filmmaking that makes Sachs’ most recent work, Carolee, Barbara and Gunvor, such a particularly wonderful piece. The short film doesn’t expose the stories of just any subjects; it looks at the lives of three creative giants who work with the moving image: Carolee Schneemann, Barbara Hammer, and Gunvor Nelson. With filmmakers balancing out both sides of the lens, the collaboration between filmmaker and subject reaches superheroine proportions.

Shot on 8mm and 16mm film, the soft colors and square aspect ratio of the film pull the viewer out of contemporary times. In the first image of the film, a cat is perched on a tree limb. In the next, the cat is acting as sentinel on a porch. The camera looks from the inside of a house out, framing the cat in a doorway. This moment jars me. I hear the voice of Schneemann discussing her entry into the medium of moving images, but the picture quality, the cat, the framing—it all conjures images of Schneemann’s own Fuses. For a moment, I wonder if I’m actually looking at Schneemann’s footage, but the tell-tale painted film frames, frenetic cuts, and abstraction of her work are absent.

Sachs’ camera casually captures mundane moments at Schneemann’s upstate New York home with beautiful, compositional precision. Schneemann describes moments ranging from her first experience with a Bolex camera to her desire to film the ordinariness of light coming through a hospital window. While she describes it, Sachs captures the sentiment; Schneeman is seen talking on the phone, hanging laundry, looking at mail. Sachs also prioritizes otherwise subtle images in and around the home: a dead bird on the porch, light coming through the window, and shots of greenery around the yard. In this piece, collaboration comes in the form of homage and interpretation.

Next, the film moves to the voice and image of Barbara Hammer. Of the film’s three subjects, Hammer is perhaps the most performative of the bunch. In a compositionally stunning scene, Hammer, at turns, walks and jogs the length of an iron fence in New York’s West Village. She repeats this several times, her body mingling with the long shadows cast by the iron slats. Eventually, she addresses the presence of Sachs’ camera. She stops, stares into it—challenges it—until Sachs pulls the camera skyward. A moment later, Hammer is on the ground, bathed in the fence’s shadows and smiling. Accompanying these images is Hammer’s forever youthful voice, explaining her love of performance both with and without her camera.

From here, the viewer moves into Hammer’s studio space to watch her toy with window blinds and choreograph film cameras as she slides them across her table. She discusses identity, and that discussion is punctuated with another challenge to Sachs’ camera; Hammer points the lens of a camera right back at her.

The final section of the triad takes the viewer to a montage of images that focus on the natural: flowers, ducks, a pond, and landscape greenery. There is no audio soundtrack for the first portion of this section: no music and no narration. The faintest sound of birds in the distant background can be missed unless the volume is set to high. Finally, the voice of Gunvor Nelson cuts the silence. It joins the images, describing Nelson’s entry into film and her impending exit from it as well. The images in this section of the film seem crisper, perhaps to reflect the camera Nelson holds in her hands—a digital Nikon. As Nelson and her camera interact with flowers and landscape, Sachs’ camera watches. Eventually, the two artists end up lens to lens, looking down a barrel at one another’s craft.

Carolee, Barbara and Gunvor is an exquisite dance shared by filmmakers and their literal and metaphorical lenses. It’s also a wonderful journey of nostalgia. The look of the 8mm and 16mm film paired with the subject matter easily takes the viewer back to the innovative first moments of women’s experimental filmmaking.

“In Search of a Feminist Sensibility”

2/24/2019

by Adina Glickstein

Another Gaze (excerpted here)

Is this a feminine sensibility? (This question) is at play in Carolee, Barbara & Gunvor (2018), Lynne Sachs’ portrait of three trailblazing experimental filmmakers, which premiered at MoMa’s Documentary Fortnight last year. In a Derenesque wink, the opening image is a cat, as Schneemann’s voice drifts in from the space offscreen. She remembers her first camera – a Brownie – and how holding it made filmmaking feel like “an inevitability”. Sachs’s camera, as if searching for Schneemann, pans around an empty room—a nod to Deren’s Meshes, and tinged with Akerman, too. Before any of the film’s titular subjects even appear on camera, Carolee, Barbara & Gunvor pulsates with the energy of feminist experimental cinema’s kindred trailblazers. Common threads are explicated, teased out by the subjects’ accounts, yet left open-ended as brevity is forced by the film’s short runtime.

In her section of the triptych, Schneemann recalls the challenge of convincing a male friend to lend her his Bolex: he resisted “as if I would bleed on this precious machinery”. She admits that she didn’t really know how to use it. Yet we know that the spirit of determination – so distinct in her oeuvre – won out, because now she’s on the other side of the camera. Next, we see Hammer. In contrast to the disembodied voice from Vever – made frail by poor cell connection and increasingly-advanced cancer – she is vivacious, running through the West Village, clowning for the camera. She recounts a foundational anecdote of her practice: on a detour from another motorcycle ride she was sidetracked by a crop of leaves in striking red. As if compelled by the goddess, she took out a bifocal lens from her optometrist and placed it in front of the camera, moving while she filmed. The finished project was a sublime manifestation of exactly how she’d felt when the leaves first caught her eye. , This embrace of openness and contingency was, for Barbara, fundamentally feminine – “I could make the inside of myself show on the outside” – and a release from the schizophrenic pull of rigidly-gendered rules for expression.

The last and longest section of Sachs’s film opens with a series of lingering close-ups of flowers. “After seeing a few of Bruce Bailey’s films, I understood that I, also as a single artist, could try.” In her childhood village in Sweden, Gunvor Nelson paces herself through what she has decided will be the final three projects of her career. There is a certain and deliberate slowness in her approach. She struggles to find tech support for her DSLR, but adapts to this challenge, finding eagerness and excitement in “calmly working” with stills. Sachs opts for a drawn-out rhythm in this vignette, as meandering shots of the surrounding nature recall the particular intimacy of Nelson’s work. This extends to her current process: even amidst technological change, she is invested in listening to her images, we sense, not bludgeoning them into some preordained vision.

These two shorts give us insight into seven women: Barbara Hammer, Maya Deren, Carolee Schneemann, and Gunvor Nelson as subjects and speakers; Lynne Sachs and Deborah Stratman from behind the camera. Watching both films, I wonder what connections there are to be drawn. Does the recent surge in filmic portraits of female trailblazers point towards a ‘feminine sensibility’, long overdue for historical recognition? I’m hesitant to speak about any ‘shared themes’ across the layered, nuanced careers that constitute this genealogy, lest these similarities be construed as an essentialised roadmap. How can we identify the beauty that comes from rejecting the strictures of masculine ways-of-being in the world without mummifying it, crystallizing these artists’ irreducible vibrancy into a prescriptive binary formula?

The key might lie in situating their work within experimental cinema’s challenging, unfeminist history. Reflecting on her mid-Sixties collaboration with Stan Brakhage, Schneemann laments: “Whenever I collaborated, went into a male friend’s film, I always thought I would be able to hold my presence, maintain an authenticity. It was soon gone, lost in their celluloid dominance.” Cat’s Cradle is hardly the only masterwork of structural film to suggest a sort of Abstract Expressionist-adjacent machismo. Against this backdrop, the nexus of similarities between Schneemann, Deren, Nelson, Sachs, and Stratman becomes explicable not as the record of some intrinsically-female way of seeing and filming the world, but as the product of work: a shared undertaking invested in upending experimental cinema’s more problematic attitudes and replacing them with a new hierarchy of aesthetic values: adaptability, intimacy, and tenderness. Only when we honour these values, in all their many manifestations across these seven artists’ careers, can we begin to construct the kind of feminist genealogy¹ that film history so urgently requires.

In Search of a Feminst Sensibility: Two New Films by Deborah Stratman and Lynne Sachs (excerpt)

By Adina Glickstein from Another Gaze Feb. 2019

Is this a feminine sensibility? A similar question is at play in Carolee, Barbara & Gunvor (2018), Lynne Sachs’ portrait of three trailblazing experimental filmmakers, which premiered at MoMa’s Documentary Fortnight last year. In a Derenesque wink, theopening image is a cat, as Schneemann’s voice drifts in from the space offscreen. She remembers her first camera – a Brownie – and how holding it made filmmaking feel like “an inevitability”. Sachs’s camera, as if searching for Schneemann, pans around an empty room—a nod to Deren’s Meshes, and tinged with Akerman, too. Before any of the film’s titular subjects even appear on camera, Carolee, Barbara & Gunvor pulsates with the energy of feminist experimental cinema’s kindred trailblazers. Common threads are explicated, teased out by the subjects’ accounts, yet left open-ended as brevity is forced by the film’s short runtime. In her section of the triptych, Schneemann recalls the challenge of convincing a male friend to lend her his Bolex: he resisted “as if I

would bleed on this precious machinery”. She admits that she didn’t really know how to use it. Yet we know that the spirit of determination – so distinct in her oeuvre – won out, because now she’s on the other side of the camera. Next, we see Hammer. In contrast to the disembodied voice from Vever – made frail by poor cell connection and increasingly-advanced cancer(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FMeoAx9dZkI) – she is vivacious, running through the West Village, clowning for the camera. She recounts a foundational anecdote of her practice: on a detour from another motorcycle ride she was sidetracked by a crop of leaves in striking red. As if compelled by the goddess, she took out a bifocal lens from her optometrist and placed it in front of the

camera, moving while she filmed. The finished project was a sublime manifestation of exactly how she’d felt when the leaves first caught her eye. This embrace of openness and contingency was, for Barbara, fundamentally feminine – “I could make the inside of myself show on the outside” – and a release from the schizophrenic pull of rigidly-gendered rules for expression. The last and longest section of Sachs’s film opens with a series of lingering close-ups of flowers. “After seeing a few of Bruce Bailey’s films, I understood that I, also as a single artist, could try.” In her childhood village in Sweden, Gunvor Nelson paces herself through what she has decided will be the final three projects of her career. There is a certain and deliberate slowness in her approach. She struggles to find tech support for her DSLR, but adapts to this challenge, finding eagerness and excitement in “calmly working” with stills. Sachs opts for a drawn-out rhythm in this vignette, as meandering shots of the surrounding nature recall the particular intimacy of Nelson’s work. This extends to her current process: even amidst technological change, she is invested in listening to her images, we sense, not bludgeoning them into some preordained vision.

These two shorts give us insight into seven women: Barbara Hammer, Maya Deren, Carolee Schneemann, and Gunvor Nelson as subjects and speakers; Lynne Sachs and Deborah Stratman from behind the camera. Watching both films, I wonder what connections there are to be drawn. Does the recent surge in filmic portraits of female trailblazers point towards a ‘feminine sensibility’,

long overdue for historical recognition? I’m hesitant to speak about any ‘shared themes’ across the layered, nuanced careers that constitute this genealogy, lest these similarities be construed as an essentialised roadmap. How can we identify the beauty that comes from rejecting the strictures of masculine ways-of-being in the world without mummifying it, crystallizing these artists’ irreducible vibrancy into a prescriptive binary formula? The key might lie in situating their work within experimental cinema’s challenging, unfeminist history. Reflecting on her mid- Sixties collaboration with Stan Brakhage, Schneemann laments (https://www.revolvy.com/folder/Films-directed-by-Stan-Brakhage

/544076): “Whenever I collaborated, went into a male friend’s film, I always thought I would be able to hold my presence, maintain an authenticity. It was soon gone, lost in their celluloid dominance.” Cat’s Cradle is hardly the only masterwork of structural film to suggest a sort of Abstract Expressionist-adjacent machismo. Against this backdrop, the nexus of similarities between Schneemann, Deren, Nelson, Sachs, and Stratman becomes explicable not as the record of some intrinsically-female way of seeing and filming the world, but as the product of work : a shared undertaking invested in upending experimental cinema’s more problematic attitudes and replacing them with a new hierarchy of aesthetic values: adaptability, intimacy, and tenderness. Only when we honour these values, in all their many manifestations across these seven artists’ careers, can we begin to construct the kind of feminist genealogy that film history so urgently requires.