Category Archives: SECTIONS

This Camera Fights Fascism in Otherzine

This Camera Fights Fascism:

A Personal Survey of Cinemas of Resistance

by Lynne Sachs

It’s been one horrible beginning of the year in America, and as you read this piece you will certainly know more than I do about the first few days, weeks, months and (aargh!) years of a Trump presidency. After marching with hundreds of thousands of other women and men in Washington D.C. on January 21, 2017, I decided that I would put out a call for films of any kind that would become a publically accessible collection of moving image pieces we would call ‘Cinema of Resistance’. Through a public social media request, I asked people from anywhere in the world to send me their video-witnessing of the Women’s March, wherever they experienced it, and after that to send any manifestations of public challenges to the message and the actions of our new President. For this project, I am not necessarily looking for polished works by people who call themselves filmmakers, but rather documents of resistance, beginning with the Women’s March, by anyone with a camera. There are already a whole range of videos in the collection now, including powerful material from Red States like Alaska and Nebraska – real proof that oppositional viewpoints exist where you least expect them and most respect them. Take a look at the growing collection HERE and send your own YouTube links to me to add to the collection. [Please find my email address below.]

And Then We Marched by Lynne Sachs (Cinema of Resistance, footage from the Women’s March on Washington, 2017)

As a filmmaker and a long-term progressive activist, I have been thinking and talking about the connection between our media practice and the crisis that is our current political situation. From the environment to reproductive health to immigration, Donald Trump is trying to dismantle every aspect of the Obama legacy. And so, with this in mind, I decided to turn to a selection of performance related acts of resistance going back as far as the 1960s that have shaken my own Weltanschauung, and forced me to think about the responsibilities of an artist during times of tumult.

In Kazuo Ishiguro‘s novel An Artist of the Floating World (1986) a Japanese painter reflects on his life during and after World War II. In his candid first-person narration, Ishiguro‘s protagonist confronts his own complicity with the totalitarian state as a producer of propagandistic paintings. Once we as readers realize that the narrator is struggling to understand his own confusion about his relationship to the political and commercial institutions around him, we begin to compare his ambivalence to our own, as artists, citizens, and human beings.

This series of reflections represents my personal survey of political actions, films, and performances that push our understanding of the delicate, potentially explosive impact of art, specifically media, in repressive environments, states, and institutions.

On May 17, 1968 nine Vietnam War protesters, including a nurse, an artist and three priests, walked into a Catonsville, Maryland draft board office, grabbed hundreds of selective service records and burned them with homemade napalm. This disparate band of activists chose to break the law in a defiant, poetic act of civil disobedience – what I would call a performance piece with profound consequences. Led by renowned priests and brothers Daniel and Phillip Berrigan, the Catonsville Nine planned their action as a visual statement against the Vietnam War, knowing full well that their collective decision would lead to years of imprisonment. An integral part of their planning was their notification to the press. Each phase of the action was documented by a local television crew that had been notified well ahead of time. Without a bona fide news agency’s filming of this production, the political resonances of this visionary gesture would be lost to us now, almost a half-century later. Ever since I first saw this archival material, I knew that its importance would echo in both the world of politics and art, as a manifestation of a radical form of resistance. In 2001, I made Investigation of a Flame, an experimental documentary on the Nine’s action and the aftermath.

Investigation of a Flame by Lynne Sachs, 2001.

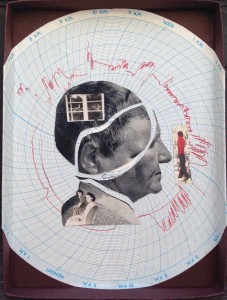

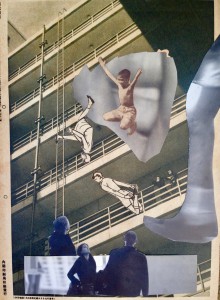

Around the same that the Catonsville Nine were encouraging a Baltimore television news crew to film their ritualized act of civil disobedience, performance artist Vito Acconci was producing his own form of self-reflexive photography-based disruptions. In 2016, PS1/Museum of Modern Art presented an exhibition of Acconci’s media work in New York City, Where We Are (Who Are We Anyway?)

In a rare, extraordinarily comprehensive display of his autobiographical performance work, viewers were able to see a wide array of Acconci’s photo series and Super 8mm films. As his distributor Video Data Bank writes, Acconci “positioned his own body as the simultaneous subject and object of the work,” in a radical calling to question of male identity and hegemony. Looking back at his Drifts, for example, forces us to think about the current immigration blockades facing so many foreigners trying to enter the United States – legally – from Mexico to multiple countries in the Middle East. With the theme of OC’s “Cinemas of Resistance” in mind, I share three of Acconci’s works:

In 1970, Acconci created Drifts by documenting himself doing the following action:

- Rolling toward the waves as the waves roll toward me; rolling away from the waves as the waves roll away from me.

- Lying on the beach in one position, as the waves come up to varying positions around me.

- Using my wet body: shifting around on the sand, letting the sand cling to my body.

This eloquent series of photographs of Acconci’s body rolling in the waves slapping against the beach compels us to reflect upon the flow of human beings coming and going from sea to land, from nowhere to somewhere, from one country to the next – either with the same ease as the waves or struggling against artificial borders created by the whims of a state – be it only vaguely democratic or fully totalitarian.

In two Super 8mm films, Acconci again simultaneously performs and directs an action that forces us to think about the position of audience and actor. In Blindfolded Catching, we look at the complex relationship between a performer/entertainer and the spectators who are watching him. Acconci challenges the conventions of this relationship in a startlingly violent dynamic that makes us think about the activating presence of the camera in torture scenarios we’ve witnessed recently through public media from Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo.

Blindfolded Catching (Super 8 film, b/w, 3 min.,1970)

Fixed camera shoots me, full-body, standing blindfolded with my back to the wall; from off-screen, rubber balls are thrown at me, one at a time, over and over again. I’m trying to catch the ball I can’t see…I’m raising my arms up in front of my face, I’ve anticipated when the next ball will be thrown. I’m wrong, my motions are wasted. I’m hit by a ball, my body doubles over, it’s too late to protect myself.

And lastly, amongst the many thought-provoking films created by Vito Acconci in the early 1970s, I find Conversions to be one of the most fascinating interpretations of sexuality, pornography, and power. In this film, Acconci shakes up everything you know about male/female relations.

Link to : https://archive.org/details/ubu-acconci_conversions

Conversions (Super 8mm film, b/w, 6 min., 1970)

Two naked bodies on the screen: we’re all bodies – my head is out of the film frame, her face is lost in my body. The camera jerks around us, zooms in and out, looking for the right shot. Kathy Dillon, kneeling behind me, takes my penis in her mouth. With my penis confined, with my penis gone, I’m exercising (running in place, kicking, bending, stretching, jumping) – all the while, she’s trying to keep my penis lost in her mouth. As the camera moves in front of us, as the camera zooms in to my groin, my body has a vagina.~Vito Acconci

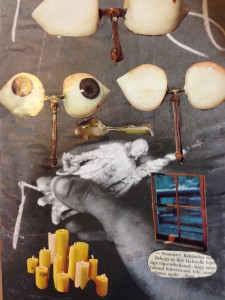

I first saw the films of Marie Louise Alemann (1927 -2015) in a 2016 screening at Anthology Film Archives in New York City. This one-evening exhibition marked the premiere of her oeuvre in the United States, roughly 40 years after its creation in the mid-1970s. Alemann, an emigré from Germany, understood the potential that film had for articulating anger and resistance. Knowing that her work was created during Argentina’s “Dirty War”, a time in which military forces and death squads hunted down and killed left-wing dissidents, I was curious to see what kind of work she was able to create in this era of national dictatorship. In Autobiográfico 2 (1974), she filmed herself bound by ropes and then releasing herself in an act of sensual, self-appointed liberation.

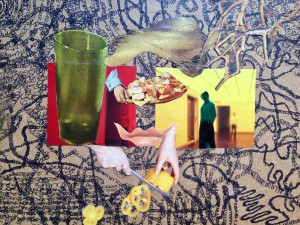

While in Buenos Aires in 2010, I spent an afternoon talking with Narcisa Hirsch, who worked closely with Alemann, about Marabunta, their performance and corresponding film collaboration. A ‘marabunta’ is a gigantic Brazilian ant that lives in the Amazon. Hirsch explained that their interpretation of this small but ferocious insect “served as a metaphor for people eating everything that they could find in their way.” Hirsch, Alemann and the other women in their artist collective made a huge sculpture of a human skeleton and covered it with food. Inside the skeleton were live pigeons painted with fluorescent colors. They mounted this sculpture in Buenos Aires near the doors of a movie theater showing Antonioni’s film Blow-Up (1966), and all the audience members were forced to look at the sculpture as they exited the film theater. Because the collective filmed the day-long creation and spontaneous exhibition of the Marabunta, their act of defiance against the male-dominated European Art Cinema of the 1960s is available to us today. Since the movie-goers were encouraged to eat the food that comprised the sculpture, they became complicit participants in this “biting” yet hilarious production. On many levels, Alemann and Hirsch’s resulting experimental film becomes an early example of a kind of expanded cinema that would, in our own imaginations, cannibalize Antonioni’s more “bourgeois” production.

Marabunto film (16mm ) by Narcisa Hirsch, Marie Louise Alemann y Walther Mejía

In the spring of 2016, I attended Microscope Gallery’s Brooklyn screening exhibition of Florida-based experimental filmmaker Christopher Harris’ films. This was to be my first opportunity to see a selected program of Harris’ work while he was there to discuss those issues that are most near and dear to him as a maker. Harris’ films are visually arresting, politically provocative, and sensitive — rarely have I watched such a nuanced, ambitious series of films that make you think for the hours, days and years that follow. His films and installations offer a remarkable opportunity to think about the ways that personal cinema can challenge assumptions about the acquisition of historical knowledge. Harris’ radical approach to historiography itself places his performative works in a new category of cinema’s counter culture.

In Harris’ Hallimuhfack (2016), a performer lip-syncs to the actual voice of renowned African-American author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston as she describes her method of documenting early Black folk songs in her home-state of Florida. According to Harris, “The flickering images were produced with a hand-cranked Bolex so that the lip-sync is deliberately erratic and the rear-projected, grainy, looped recycled images of Masai tribesmen and women become increasingly abstract as the audio transforms into an incantation.”

In A Willing Suspension of Disbelief ( 2014), Harris “re-stages slave daguerreotype in order to examine scientific racism.” Both pieces embrace the challenges, unpredictability, and evanescence of 16mm filmmaking as a form of anachronistic “resistance” to the more commercial, precise high-production “values” of digital. By working with Black women performers who become collaborators in his charged resurrection of the past, Harris offers both his female actors and us as an audience the chance to examine and confront the evils of our shared American story.

And finally, I’ll address Julian Rosenfeldt’s Manifesto which I saw in early 2017 in perhaps the largest single-room exhibition space in New York City, the Park Avenue Armory. According to the catalogue, material for this 13-screen installation is drawn from the writings of Futurists, Dadaists, Fluxus artists, Suprematists, and Situationists. Rosenfeldt weaves together their ideas with the musings of individual artists, resulting in a collage of artistic declarations. Hollywood actress Cate Blanchett performed all thirteen different protagonists as each screen attempts to articulate a contemporary call to action. Manifesto is by far the grandest, most expensive, most polished of the film works I have discussed in this essay. Clearly, critics, curators and the European and American art-going public are keen on celebrating the theoretical and historical foundations on which the Rosenfeldt builds his query into historical, political and social dialectics. We learn a great deal about the echoes of a fantastic array of thinkers, but do we come away from this work ready to engage with the world? In the exhibition catalogue, it seems to me, the emphasis is on the work’s “style that beautifully pays tribute to iconic film directors,” rather than to the ideas that he is ostensibly embracing. This is, sadly, a cinema about resistance but not a cinema of resistance.

I first met Father Daniel Berrigan (1921 – 2016), the Jesuit priest whose defiant protests helped shape a bold, grass-roots opposition to the Vietnam War, in 1998 when I was making Investigation of a Flame (2001). Little did I know that my interview with him about his role in the Catonsville Nine would lead to one of the deepest and most meaningful friendships of my life. Daniel was a poet and an activist, and both of these aspects of his being contributed to his life-long commitment to speaking out against injustice. Today, in this America of 2017, all of us must grapple with how to integrate our creative work into our lives as politically engaged members of a society in a disturbing moment of flux. We can certainly turn to the films of Acconci, Alemann, Harris and others as examples of work that expand our understanding of the way that a moving image – be it elliptical or explicit – can become a spark for thinking and action.

Note on Title: “This Machine Kills Fascists” is a message that Woody Guthrie placed on his guitar in 1941,which inspired many subsequent artists.

To be included in our Cinema of Resistance collection, upload your video to YouTube and send your link to:

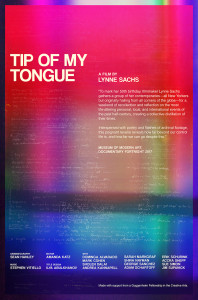

Tip of My Tongue

Tip of My Tongue (80 min. 2017)

a film by Lynne Sachs

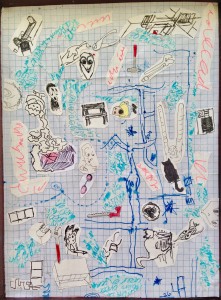

To celebrate her 50th birthday, filmmaker Lynne Sachs gathers together other people, men and women who have lived through precisely the same years but come from places like Iran or Cuba or Australia or the Lower East Side, not Memphis, Tennessee where Sachs grew up. She invites 12 fellow New Yorkers – born across several continents in the 1960s – to spend a weekend with her making a movie. Together they discuss some of the most salient, strange, and revealing moments of their lives in a brash, self-reflexive examination of the way in which uncontrollable events outside our own domestic universe impact who we are. As director and participant, Sachs, who wrote her own series of 50 poems for every year of her life, guides her collaborators across the landscape of their memories. They move from the Vietnam War protests to the Anita Hill hearings to the Columbine Shootings to Occupy Wall Street. Using the backdrop of the horizon as it meets the water in each of NYC’s five boroughs as well as abstracted archival material, TIP OF MY TONGUE becomes an activator in the resurrection of complex, sometimes paradoxical reflections. Traditional timelines are replaced by a multi-layered, cinematic architecture that both speaks to and visualizes the nature of historical expression. (Anthology Film Archives Calendar)

“The past is deconstructed. Unremembered. Reconstructed. A charmingly captivating ride through a constructed dream-party full of reflection and recollection. Lynne Sachs’ inspired use of archival footage and poetry is wonderfully complimented by Stephen Vitiello’s vibrant music and Sean Hanley’s pleasurably stimulating visual style. The personal living memory processed through poignant imagery and evocative scribblings offer a great account of (un)known global history. Stephen Vitiello’s hypnotic music in Sachs’ latest ‘Film About a Father Who’ was a match made in Cinema Paradise. The collaboration was one of the primary reasons behind my desire to watch Tip of My Tongue. The expectations were surpassed by this enchanting documentary piece.”

Sibi Sekar

Sibi Sekar was born on April 29th, 1997 in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. Sibi fell in love with cinema at an early age upon viewing the works of directors such as Luis Buñuel and Sergei Parajanov. His works have been screened at over thirty festivals across five continents. He recently graduated from Indian Institute of Technology, Madras with a master’s degree in Humanities and Social Sciences and is currently working on explorative films that are primarily an ascetic representation of resistance. The thematic dispositions of his films concern the symbolic depiction of being, nothingness and the transcendental space.

RECENT PRESS

“Tip of My Tongue is entrancing. As someone who was born in the mid ’90s, I am distantly removed from many of the events mentioned in the film. To hear personal accounts of the Iranian revolution or Nixon’s resignation was surreal for me, offering me a glimpse into a past I never experienced. I can only imagine the memories Tip of My Tongue would unearth for those who have lived through those same events. This film offers viewers a brilliant visual representation of what it means to remember. The metaphor one participant uses to describe the nature of political change can easily be applied to the human brain: ‘It’s like the paradigm of being part of an organism rather than part of a machine.’ It’s hardly simple, or even logical, but isn’t the complexity what makes it so interesting?” (Agnes Films, http://agnesfilms.com/reviews/review-of-tip-of-my-tongue-directed-by-lynne-sachs/)

“A mesmerizing ride through time, a dreamscape full of reflection, filled with inspired use of archival footage, poetry, beautiful cinematography and music. Raises the question of how deeply events affect us, while granting us enough room to crash into our own thoughts, or float on by, rejoicing in the company of our newfound friends.” (Screen Slate, Sonya Redi https://www.screenslate.com/features/366)

“A beautiful, poetic collage of memory, history, poetry, and lived experience, in all its joys, sorrows, fears, hopes, triumphs, and tragedies … rendered in exquisite visual terms, creating an artful collective chronicle of history.” (Christopher Bourne, Screen Anarchy,

http://screenanarchy.com/2017/02/nyc-weekend-picks-feb-24-26-jordan-peele-curates-oscar-nominated-shorts-and-best-picture-winners-doc-gallery.htm)

“An examination of one generation’s complex and diverse navigation between public and private experience.” (“Tip of My Tongue: Film Scratches: Public Stories, Private Memories” review in Film International) http://filmint.nu/?p=20232

“The past is unearthed, turned over and reconsidered in new and astonishing ways by three filmmakers marking their return to Doc Fortnight …. To mark her 50th birthday, filmmaker Lynne Sachs gathers a group of her contemporaries—all New Yorkers but originally hailing from all corners of the globe—for a weekend of recollection and reflection on the most life-altering personal, local, and international events of the past half-century, creating a collective distillation of their times. Interspersed with poetry and flashes of archival footage, this poignant reverie reveals how far beyond our control life is, and how far we can go despite this.” (The Museum of Modern Art)

Featuring: Dominga Alvarado, Mark Cohen, Sholeh Dalai, Andrea Kannapell, Sarah Markgraf, Shira Nayman, George Sanchez, Adam Schartoff, Erik Schurink, Accra Shepp, Sue Simon, Jim Supanick

Music – Stephen Vitiello; Camera – Sean Hanley, Ethan Mass, Lynne Sachs; Editing – Amanda Katz; Archival Research – Craig Baldwin; Sound Mix – Damian Volpe

Selected Screenings:

- Closing Night Film, Documentary Fortnight, Museum of Modern Art (https://www.moma.org/calendar/events/2823)

- Festival EDOC – Encuentros del Otro Cine in Quito, Ecuador

- Athens Film & Video Festival, Athens, Ohio (http://athensfilmfest.org/tip-of-my-tongue/)

- Anthology Film Archives, NYC (http://anthologyfilmarchives.org/film_screenings/calendar?view=list&month=5&year=2017#showing-47368)

- Currents New Media Festival, Santa Fe, New Mexico (https://currentsnewmedia.org/events/experimental-documentary-series-feature/)

- Museum of Modern Art Documentary Fortnight Closing Night Film; Athens Film & Video Festival; Indie Memphis; Festival Encuentros del Otro Cine (EDOC), Ecuador; Currents New Media Festival, Santa Fe; Maine International Film Festival; Wexner Center for the Art; San Francisco Cinematheque; Mill Valley Film Festival; Anthology Film Archives; Three Rivers Film Festival, Pittsburgh Center for the Arts; Lightbox Theater, Philadelphia; Wellesley College; Hallwalls Center for the Arts; Union Docs Center for Documentary, Williamsburg, NY.

Supported by a Guggenheim Fellowship in the Creative Arts and a MacDowell Colony Residency

For inquiries about rentals or purchases please contact the Cinema Guild. For international bookings, please contact Kino Rebelde.

MM Serra discusses films of José Rodriguez Soltero

Puerto Rican filmmaker José Rodriguez Soltero (1943 – 2009) was a significant figure in the New York underground art scene during the mid-1960s and early 1970s. His films were frequently included in Filmmakers’ Cinematheque programs. He was featured in Film Culture and written up in Jonas Mekas’s Movie Journal column in the Village Voice, and was the friend and collaborator of Mario Montez, Charles Ludlam and Jack Smith.

Here MM Serra, Executive Director of the Filmmakers Cooperative in New York City, discusses the 1960s Queer, count-culture, underground films of Rodriguez Soltero with friend and filmmaker Lynne Sachs. The Coop has recently preserved and digitized his films for the world to see! This interview was conducted in March, 2017 prior to Sachs’s presentation of “Lupe” at Beta Local (www.betalocal.org) in San Juan, Puerto Rico, which may be (we are not sure) the first screening of the film in its entirety in the filmmaker’s “mother” country.

“Lupe” (1966 – 16mm, color, sound – 49:05 ) by José Rodriguez Soltero is an underground classic of the stature of Jack Smith’s “Flaming Creatures”, Kenneth Anger’s “Scorpio Rising”, George Kuchar’s “Hold Me While I’m Naked”, or Andy Warhol’s “The Chelsea Girls”. It is ostensibly a biopic of Lupe Velez inspired by Kenneth Anger’s sketch of the Mexican spitfire in Hollywood Babylon and, stylistically, by Von Sternberg’s Marlene Dietrich vehicles. Rodriguez Soltero takes some liberties with the facts and produces a color-saturated, gorgeous dime-store baroque that tells of Lupe’s rise from whoredom to stardom, her fall into fractured romance and suicide, and her ascension into the spirit world. It is consistently inventive and surprising, and wrapped in a dense soundtrack that combines, Elvis, Cuban boleros, Spanish flamenco, The Supremes, and Vivaldi. It features some of the main players of the Ridiculous Theatrical Playhouse (Charles Ludlam plays a keen lesbian seducer and Lola Pashalinsky, Lupe’s maid). Mario Montez never looked better; no wonder this was his favorite film. Whether they know it or not, Pedro Almodovar, Vivienne Dick, and Bruce LaBruce have a godfather in José Rodriguez Soltero.(Juan Suarez )

For more information on the films of Jose Rodriguez Soltero, contact the NY Filmmakers Cooperative at 212 267 5665 or http://film-makerscoop.com/.

Many thanks to the National Film Preservation Foundation.

And Then We Marched

And Then We Marched

3 1/2 min. (digital from Super 8 and 16 mm film)

by Lynne Sachs

“One day after the presidential inauguration in January 2017, the Womenʼs March took place in Washington D.C. Footage from the demonstration, shot with Super8 camera, is combined with archival footage of the protest marches from various moments in the US history. A visual whirl of the protesters᾽ faces and banners is accompanied by a childʼs voice which is trying to express as accurately as possible what it means to fight for oneʼs own rights.”

— Ji.hlava International Documentary Festival

Filmmaker Lynne Sachs shoots Super 8mm film of the first Women’s March in 2017 in Washington, D.C. and intercuts this recent footage with archival material of early 20th Century Suffragists marching for the right to vote, 1960s antiwar activists and 1970s advocates for the Equal Rights Amendment. Sachs then talks about the experience of marching with her seven-year old neighbor who offers disarmingly insightful observations on the meaning of their shared actions. With commentary by Sophie D. and editing by Amanda Katz.

Screenings: Other Cinema, San Francisco; Workers Unite Film Festival; KOSMA Gwangju International organized by the Korean Society of Media & Arts; Microscope Gallery, NYC; Metrograph Theater, NYC; Rotterdam International Film Festival 2021; Ji.hlava International Documentary Festival, Czech Republic 2022.

For inquiries about rentals or purchases please contact Canyon Cinema or the Film-makers’ Cooperative. And for international bookings, please contact Kino Rebelde.

This film is currently only availible with password. Please write to info@lynnesachs.com to request access.

Tip of My Tongue at Athens International Film and Video Festival

http://athensfilmfest.org/tip-of-my-tongue/

Tip of my Tongue

Director: Lynne Sachs

Documentary

80 min

USA

Competition Feature

Thursday, April 6, 3:00 PM

Twelve New Yorkers born in the early 1960s across several continents “visit” every year of their lives in a brash, self-reflexive experiment about what it’s meant to live in America over the last half century. Director and participant Lynne Sachs, who wrote her own series of 50 poems for every year of her life, guides her collaborators across the landscape of their memories. She gives each person the same historical timeline as a catalyst for an exploration of the relationship between their personal lives and the times in which they have lived. Initially strangers with nothing in common but their age, the group works together writing, performing and filming.

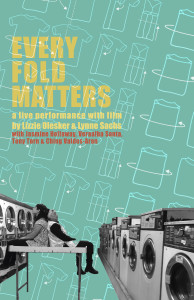

NYU’s Asian Film and Media Initiative & Cinema Studies present Every Fold Matters

NYU’s Asian Film and Media Initiative & Cinema Studies present

EVERY FOLD MATTERS

Created by Lizzie Olesker and Lynne Sachs

TWO SHOWS!

Friday, March 3, 2017

3:30 PM

5:30 PM

Michelson Theater, Dept of Cinema Studies

721 Broadway, 6th Floor

NYU Tisch School of the Arts

New York, NY 10003

EVERY FOLD MATTERS is a live performance and a film project that looks at the charged, intimate space of the neighborhood laundromat and the people who work there. Set at the crossroads of a Brooklyn neighborhood, we meet three characters in a real laundromat — a uniquely social and public space that is slowly disappearing from our changing urban landscape. Based on interviews with New York City laundry workers, the project combines narrative and documentary elements as it explores personal stories of immigration, identity, money, stains and dirt.

Featuring performances by: Jasmine Holloway, Veraalba Santa, Ching Valdes-Aran.

March 3rd performances sponsored by the Asian Film and Media Initiative in the Department of Cinema Studies.

“The legacy of domestic work, the issues surrounding power, and the exchange of money for services are all potent themes which rise to the surface and bubble over in dramatic, thrilling escalations of the everyday.” (Brooklyn Rail)

“Spotlights the often-invisible workers who fold the clothes, maintain the machines and know your secrets.” (In These Times)

“The intersection of film and performance, reality and imagination, employee and customer, historical fact and personal anecdote…You made us rethink the laundromat as a site of urban convergence, where strangers (of different races, religions, languages and classes) make ritualistic visits to a public space that’s also a functional extension of their own homes.” Alan Berliner, filmmaker

EVERY FOLD MATTERS has received support from New York State Council on the Arts, Brooklyn Arts Council, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (through Dirty Laundry/Loads of Prose), Women and Media Coalition, and Fandor FIX Filmmakers.

Our collaborators include acclaimed downtown actors Ching Valdes-Aran, Jasmine Holloway, Veraalba Santa, and, film editor Amanda Katz, cinematographer Sean Hanley and sound artist Stephen Vitiello.

Open to the public free of charge.

Screen Slate Review of Tip of My Tongue

Tip of My Tongue

by Sonya Redi

Featured February 25th 2017

https://www.screenslate.com/features/366

Most moments have a terrible tendency to surround us, enveloping us and swallowing us whole, before we have time to understand or process them. Much like waves, they pass through us, sometimes violently, taking our whole body for a spin and leaving us with nothing except an intense sensation and vivid memory. Lynne Sachs‘ latest film, Tip of My Tongue , grants us the impossible gift of trying to change that—letting us comfortably, over the course of a weekend, try to process those moments which impacted us so profoundly in the last half century. Sachs’ brilliant body of work has often focused on the curious dance between histories, the personal and global, so it is no surprise that her latest film moves across a myriad of topics with skill and grace.

Though singular in scope, the film’s premise is delightfully simple. In honor of her fiftieth birthday, Sachs gathers a group of New Yorkers from around the world, whose only common trait is that they were born around the same time. Together they spend the weekend conversing and sharing their personal memories from these turbulent years, reflecting on topics ranging from the assassination of JFK to Occupy Wall Street. Through this sharing of intimate fragments we are able to feel instantly connected, as if along for the journey. Sachs creates a magical, safe space for us to get lost in conversation, as well as take a step back and unfold on our own memories, however big or small.

It’s a mesmerizing ride through time, a dreamscape full of reflection and wonder, filled with inspired use of archival footage, poetry, beautiful cinematography and music. The film flows seamlessly across the years like one of the elusive waves it is trying to catch. It raises the question of how deeply events affect us, while granting us enough room to crash into our own thoughts, or float on by, rejoicing in the company of our newfound friends.

© Jon Dieringer 2010-2017. All Rights Reserved.

Agnes Films Review of Tip of My Tongue

Review of Lynne Sachs’s Tip of My Tongue

http://agnesfilms.com/reviews/review-of-tip-of-my-tongue-directed-by-lynne-sachs/

Review by Katie Grimes

Developmental Editing by Alexandra Hidalgo

Copy Editing and Posting by Elena Cronick

Tip of My Tongue (2016). 80 minutes. Directed by Lynne Sachs. Featuring: Dominga Alvarado, Mark Cohen, Sholeh Dalai, Andrea Kannapell, Sarah Markgraf, Shira Nayman, George Sanchez, Adam Schartoff, Erik Schurink, Accra Shepp, Sue Simon, Jim Supanick.

There is history, and then there is memory. Though both are hardly objective, memory is impossible to remove from personal experience. Often, what we remember from a historical moment is a strong emotion, an intimate moment, the people and objects who surrounded us when the event took place. In Tip of My Tongue, director Lynne Sachs explores the dynamism of memory through poetry, archival footage, and personal interviews; her artful collage of moments intelligently portrays the beauty that often lies hidden in the minds of those around us.

In her film, Sachs brings together twelve New Yorkers born in the early 1960s. Though strangers, together they explore their memories of the past five decades in the intimacy of Sachs’s home. From countries as wide-ranging as Australia, Iran, and the Dominican Republic, participants relive JFK’s assassination, the AIDS epidemic, Occupy Wall Street, and more. As Sachs describes in her narration, “Together we construct a collective distillation of our times, building an inverted history of deep breaths, illness we don’t understand, assaults, the death of a princess, a struggle of a president, a lost envelope, terror. … And so we begin our memory game.”

To my delight, Sachs isn’t afraid to experiment. Her film begins with flashes of color illuminating handwritten notes. Dates accompanied by lines of poetry, some crossed out, appear too quickly to read while archival footage plays in the background. Our eyes only catch a few words here and there: Bob Dylan, Russian spies, the Vietnam War. The montage reminds us of how memories often live in our minds as fragmented, half-remembered pieces sprinkled with bursts of emotion. Throughout the film, Sachs uses close-up shots to confront viewers with the faces of those who remember. We hear them recite their stories in their own words, the intimacy of which reflects the individuality of each of their experiences. Audio is faded in and out to represent the fragility of those memories. In one scene, two participants lie in opposite directions with their heads next to each other, eyes closed. Viewers can see one participant speaking but hear the other’s voice. Like so many elements of Sachs’s film, this scene has layers of meaning. When two people think about the year 1978, two completely different moments come to mind, offering a diverse experience of history.

Tip of My Tongue is entrancing. As someone who was born in the mid ’90s, I am distantly removed from many of the events mentioned in the film. To hear personal accounts of the Iranian revolution or Nixon’s resignation was surreal for me, offering me a glimpse into a past I never experienced. I can only imagine the memories Tip of My Tongue would unearth for those who have lived through those same events. This film offers viewers a brilliant visual representation of what it means to remember. The metaphor one participant uses to describe the nature of political change can easily be applied to the human brain: “It’s like the paradigm of being part of an organism rather than part of a machine.” It’s hardly simple, or even logical, but isn’t the complexity what makes it so interesting?

The world premiere of Tip of My Tongue will include two screenings of the film at the Museum of Modern Art as a part of Doc Fortnight 2017: MoMA’s International Festival of Nonfiction Film and Media.

The screenings will be 7:30 p.m. Saturday, February 25, and 5 p.m. Sunday, February 26 in Theater 1 in the Museum of Modern Art.

View the trailer for Tip of My Tongue and click here to visit Katie Grimes’s profile.

Screen Anarchy’s Christopher Bourne Reviews Tip of My Tongue

Doc Fortnight 2017 at The Museum of Modern Art

by Christopher Bourne

This consistently rewarding survey of some of the world’s most innovative nonfiction filmmaking wraps up this weekend. Two of its best entries are by great filmmakers who have screened films before at this festival.

Lynne Sachs’ latest film Tip of My Tongue, which has its world premiere as the festival’s closing night selection, is a beautiful, poetic collage of memory, history, poetry, and lived experience, in all its joys, sorrows, fears, hopes, triumphs, and tragedies.

Sachs has previously made such experimental, hybrid documentaries as Your Day is My Night (2013) and Every Fold Matters (2016), which incorporate documentary material, live and filmed performance, personal storytelling, and aural and visual collage to explore experiences of shared private and public spaces.

In Tip of My Tongue, to mark her 50th birthday, Sachs gathers together 12 people – all fellow New Yorkers, some friends, some relative strangers – born in the 60’s and thus around her age. The film uses archival and original footage, written text, Sachs’ own poetry, and first-person narratives of memories and experiences to explore how personal, political, cultural, and social histories intersect and affect individuals in unique ways. The cultural upheavals of the 1960’s, the Vietnam War, Nixon and Reagan, the start of the AIDS epidemic, 9/11, the 2008 financial crisis, Occupy Wall Street, and other events figure greatly in the stories told by the people gathered here. The years covered here – the numbers of which are written on various surfaces throughout the film – are rendered in exquisite visual terms, creating an artful collective chronicle of history.