Lynn Hershman Leeson, Lynne Sachs and Nina Menkes are American independent, experimental filmmakers who have been making movies for three decades. Their films have been showcased at international festivals, and they’ve won numerous awards.

Which makes it all that more frustrating — to these filmmakers and their fans — that much of their work received little or no commercial distribution. Enter Fandor, the 4-year-old streaming service that specializes in independent, experimental, foreign and cult films.

Last summer, Fandor started Fix, a platform on the site that allows indie and experimental filmmakers the chance to connect with potential audiences. Fix features the work of 140 filmmakers with more being added. (Fandor is available by subscription for $6 a month.)

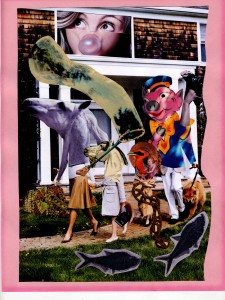

Leeson, Sachs and Menkes were filmmakers chosen for the initial Fix platform, part of an effort to spotlight female directors. Forty-eight women are featured, including such young filmmakers as Anna Frances Ewert and Penny Lane. Amanda Salazar, a spokeswoman for Fandor, said the hope is to showcase the wide spectrum of work done by female directors.

Leeson, the subject of several retrospectives on the site, has received emails from “younger people who are just discovering these pieces” on Fandor. “It reaches new audiences, and it kind of revives these works that otherwise would be difficult to see.”

Among her features and shorts streaming on the site are 1997’s “Conceiving Ada,” starring her muse Tilda Swinton, the 2002 sci-film drama “Teknolust” with Swinton and 2010’s “Women Art Revolution,” her documentary on the history of feminist art in the late 20th century that took 42 years to complete.

Leeson said she turned to filmmaking because “it combined all the elements of time and space and manipulating colors. It was a way to use all the compositional points of making art, but doing it in this fluid fashion that would reach a completely different and wider audience, even though the messages were the same.”

Despite her international acclaim, Leeson struggles to get her films produced. “I’m older, so I think if I were female and younger, it would be easier,” said Leeson, in her early 70s. “I think being my age, there are kinds of discrimination that one faces being able to do their work. It’s never been easy to make a film. ”

Or have one released.

“Teknolust,” she said, was picked up by a distributor at the Sundance Film Festival who didn’t honor the contract. Instead, “I opened it myself in New York,” she said.

But she never got discouraged, “I think art is all bred out of optimism, and you have to believe in what you are doing,” said Leeson, who’s planning a film with Swinton on genetic mutation in which the Oscar winner plays a cat.

Sachs’ films featured on Fandor include the 1994 documentary short “Which Way Is East,” a travel diary of Sachs and her sister Dana’s trip to Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam, 2006’s “States of UnBelonging,” about an Israeli filmmaker and mother who is killed in the West Bank, and 2010’s “The Task of the Translator,” an homage to Walter Benjamin’s essay of the same name.

Sachs, 53, was a photographer, painter and poet before she began to make films. “It wasn’t until I was in college and had my two years abroad in Paris that I discovered Agnes Varda and Chantal Akerman — all of these women filmmakers who had this semi-poetic approach to film,” said Sachs, the sister of director Ira Sachs (“Love Is Strange”).

“This was in the ’80s,” she said. “I had never seen any film by a woman director.”

Though Sachs noted that “there are more women in the experimental universe” than when she began, she is surprised how few female directors there are working in indie and commercial cinema.

Sachs, who has taught experimental film and video at New York University and the New School for 20 years, always asks her students to name their favorite director. She noted that none of her students has ever named a woman as their favorite filmmaker. And the sad truth, Sachs added, is that a few — even the young women in class — have difficulty naming any female director unless it is a high-profile actress-turned-director such as Angelina Jolie.

“It’s kind of shocking,” she said.

Two of Menkes’ seven features are on Fandor — 2007’s “Phantom Love” and 2010’s “Dissolution,” which was shot in Tel Aviv and is loosely based on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment.”

Described by The Times as “one of the most provocative artists in film today,” Menkes’ films are complex, dark, disturbing — and not surprisingly often met with hostility.

“The best example is to go back to my first feature, which was ‘Magdalena Viraga’ in 1986, which I made at the UCLA film school,” said Menkes, 49. “We actually got the L.A. Film Critics Assn. Award that year.”

But one student at the film school stood up after a screening and told Menkes that the story of an alienated prostitute was “the most violent movie I have ever seen. You do things Brian De Palma doesn’t do.”

The film, she said, “contains almost no actual violence at all. But it shows a woman having alienated sex, which maybe now is not as radical as it was at that time.”

And every distributor turned her down.

“Their official reason is that your film is too experimental. Indeed my films are experimental, but I think the thing that really made them say no was a gut reaction to this woman on screen not being aligned with their world view in terms of how women can be portrayed. I think that has remained an issue.”

Copyright © 2015, Los Angeles Times

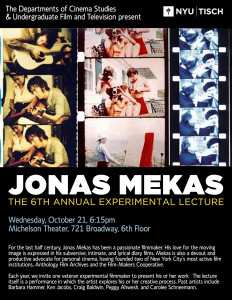

The 6th Annual Experimental Lecture

The 6th Annual Experimental Lecture