DGenerateFilms

Chinese Independent Film Lives On

A Photo Essay by Karin Chien

Dec 2, 2014

https://www.dgeneratefilms.com/post/chinese-independent-film-lives-on-a-photo-essay-by-karin-chien

Earlier this month, dGenerate Films’ Founder and President Karin Chien attended the 11th China Independent Film Festival (CIFF) in Nanjing. Many did not think the festival could happen.

In 2012, CIFF was shut down by the authorities. In 2013, the organizers carefully screened only 10 feature films and one documentary. Then, earlier this year, the Beijing Independent Film Festival (BIFF), known to show more politically sensitive films than CIFF, was violently repressed, the organizers detained, and their archive of over 1500 independent films confiscated.

Yet, from November 15-20, CIFF’s organizers managed to pull off the only festival of independent Chinese films in mainland China this year.

Below, Karin chronicles her visit to CIFF, as well as to the BIFF offices and to the opening ceremony of a new festival, the 2nd China Women’s Film Festival.

Documentary director Xu Tong (FORTUNE TELLER) answers questions about his latest film CUT OUT THE EYES, which tells the story of a blind traveling musician in Inner Mongolia. A classroom at Nanjing University of the Arts served as one of four screening venues for the 2014 China Independent Film Festival (CIFF). Because the festival was not widely publicized, in order not to draw attention from the authorities, the majority of the audience were students who saw the posters and programs around campus.

Festival volunteers carry an extra bench through the Art Museum of Nanjing University of the Arts to accommodate an overflowing audience for ACTING FOR THE GOVERNMENT by director Jia Zhitan. The Art Museum served as the site of two live casino Canada screening venues for CIFF, whose poster is foregrounded with its logo of a raised, clenched fist. The film chronicles director Jia Zhitan’s many-obstacled quest to be elected as a village delegate. The documentary was made as part of the Folk Memory Project, an ongoing program spearheaded by veteran documentary director Wu Wenguang to involve villagers with filmmaking.

Dinner and a rare reunion of veteran documentary directors and friends, including (from left) distributor/curator Nakayama Hiroki, director Yu Guangyi (TIMBER GANG), director Zhou Hao (USING, TRANSITION PERIOD), director Gu Tao (THE LAST MOOSE OF AOLUGUYA), director Xu Tong (FORTUNE TELLER), along with Yu Qiushi (Yu Guangyi’s daughter) and feature film director Li Pengfei (HEAVEN’S WILL). Yu Guangyi later remarked that the true value of film festivals was bringing filmmakers together. Gu Tao and Zhou Hao were attending the CIFF screenings of their documentaries, before traveling to Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards, where Zhou Hao would win Best Documentary for COTTON.

A closed door evening session of the Documentary Director’s Forum, where director Shu Haolun (STRUGGLE, NOSTALGIA, and 2014 CIFF short film juror) photographs director Li Xin (PREACHERS, 2014 CIFF 10 Best Documentary program) while directors Gu Tao, Yu Guangyi, Zhou Hao, Zhu Yuzhi look on.

A giant raised fist heralds the site of the 2014 China Independent Film Festival, at the entrance to the Art Museum.

A tree-lined path on campus. Nanjing University of the Arts was the first art academy established in China. Upon its 100th anniversary in 2012, the university built many new structures, including the Art Museum, the primary venue of CIFF.

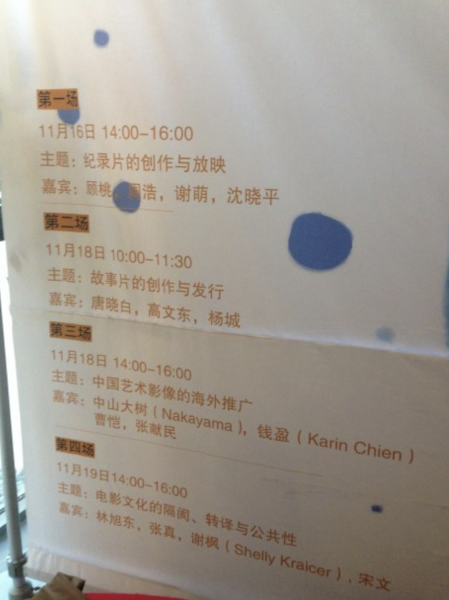

A large poster announcing daily afternoon panel discussions on the state of Chinese cinema, open to students of Nanjing University of the Arts. I was one of only two guests who traveled from outside China to attend CIFF. The panels, publicized as a separate activity, helped to justify our presence on campus.

A moderator calls director Zhao Dayong (GHOST TOWN, STREET LIFE) on speakerphone for the Q&A of SHADOW DAYS. The film premiered at the 2014 Berlin Film Festival, and is inspired by real events around “family planning” in China. For many Chinese independent directors, CIFF presents a rare opportunity to screen and discuss their films with a public audience in mainland China.

A packed nighttime screening. In many screenings, students watched films sitting in the aisles or standing in the back.

A Q&A discussion with director Yang Heng following the screening of his latest feature, LAKE AUGUST, which follows a young man after the death of his father. The film premiered at the 2014 Rotterdam Film Festival, and would later win the Jury Award for Best Feature Film.

This final panel discussion took place upstairs at the Art Museum. Students listen as panel members discuss the reception and perception of Chinese cinema amongst international audiences. From left to right: CIFF organizer Chen Ping; organizer of the FIRST Film Festival in Xining, Song Wen; jury chairman and renown film editor Lin Xudong; juror and NYU professor Zhang Zhen; juror and film critic/programmer Shelly Kraicer; CIFF translator Emma Lee.

A Q&A discussion at the main screening venue of the Art Museum. Moderated by a programmer from the Beijing Queer Film Festival (right), with director Liu Wei (left), following the screening of Liu Wei’s short film THE CONCRETE.

A golden raised, clenched fist represents the five CIFF awards, determined by two juries. The 2014 winners are:

Best Short Film – A PIECE OF TIME by Cai Jie

Jury Award for Short Film – KETCHUP by Guo Chunning

Best New Feature Film Director – THE NIGHT by Zhou Hao

Jury Award for Feature Film – LAKE AUGUST by Yang Heng

Best Feature Film – THE RIVER OF LIFE by Yang Pingdao

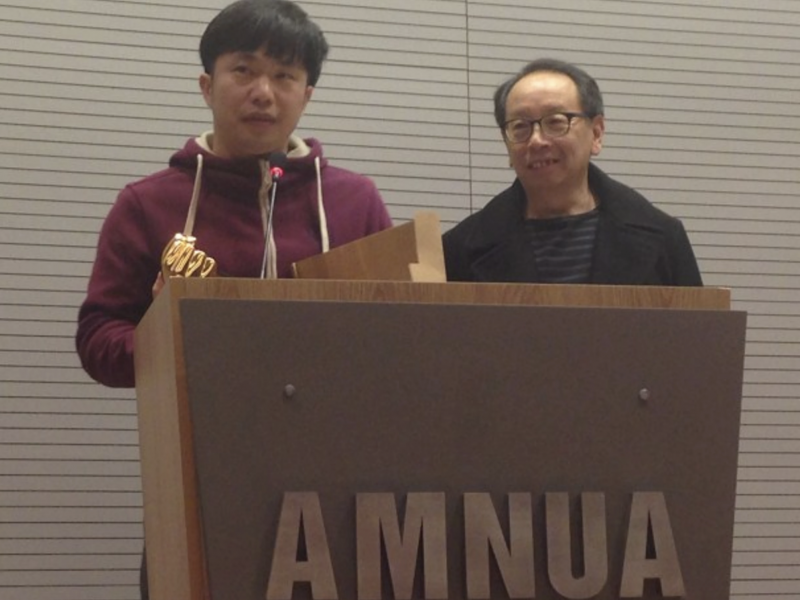

Twenty-two year old director Zhou Hao accepts the award for Best First Film for THE NIGHT while juror and CIFF co-founder Cao Kai (2nd from left) and CIFF organizer Shen Xiaoping look on. THE NIGHT premiered at the 2014 Berlin Film Festival.

Juror and film critic/programmer Shelly Kraicer reads the jury citation for LAKE AUGUST by Yang Heng, which won the Jury Award for Feature Film, while juror and NYU professor Zhang Zhen (2nd from left) and CIFF organizer Shen Xiaoping look on.

Director Yang Pingdao accepts the Best Feature Film Award for THE RIVER OF LIFE from jury chairman and renown film editor Lin Xudong. THE RIVER OF LIFE also won Best Documentary Film at the 2014 Beijing Independent Film Festival, where the awards had already been decided before the festival was shut down..

Outside the now shuttered Fanhall Films in the village of Songzhuang, an hour outside of Beijing. Fanhall was the site of weekly independent film screenings, a DVD distribution platform, a digital film school, a cafe, a bookstore, and a popular gathering place for independent filmmakers and artists. Fanhall has been closed since August 2014, when the Beijing Independent Film Festival (BIFF) was repressed by the authorities.

The newly constructed screening room at the Li Xianting Film Fund, sponsor of BIFF, in Songzhuang. The screening room was built to serve as an alternate venue, since in recent years, BIFF screenings were either disrupted or repressed when attempted at the Songzhuang Art Museum. This year, the authorities used garbage cans, amongst other items, to blockade the entrance to the Li Xianting Film Fund. No one could enter during the festival dates. Later, the entrance was completely sealed off, and no one exit either. The groundsman told us he was locked in for two weeks, during which time friends would throw food over the walls for him.

The now empty shelves of the Li Xianting Film Fund. Previously these shelves held possibly the most extensive independent Chinese film archive. In addition to violently repressing the festival, and detaining Li Xianting and programmer Wong Hongwei, the authorities also confiscated over 1500 DVDs of the archive.

The official poster for the 2014 Beijing Independent Film Festival. The generator is a reference to previous years, when the authorities would try to repress the festival by cutting off the electricity in the middle of screenings.

The empty desks at the Li Xianting Film Fund. Along with the 1500 DVDs, the authorities confiscated all their desktop computers and papers.

At the opening ceremony for the 2nd China Women’s Film Festival (CWFF). Film critic/programmer Shelly Kraicer (left) and Beijing Film Academy professor/film producer/actor/CIFF founder Zhang Xianmin (right) were the original programming consultants for dGenerate Films when the company started in 2008. The ceremony was held at the Zhengyici Peking Opera Theatre, built in 1688 and restored in 1995. It is one of the most well known and oldest wooden theatres in China.

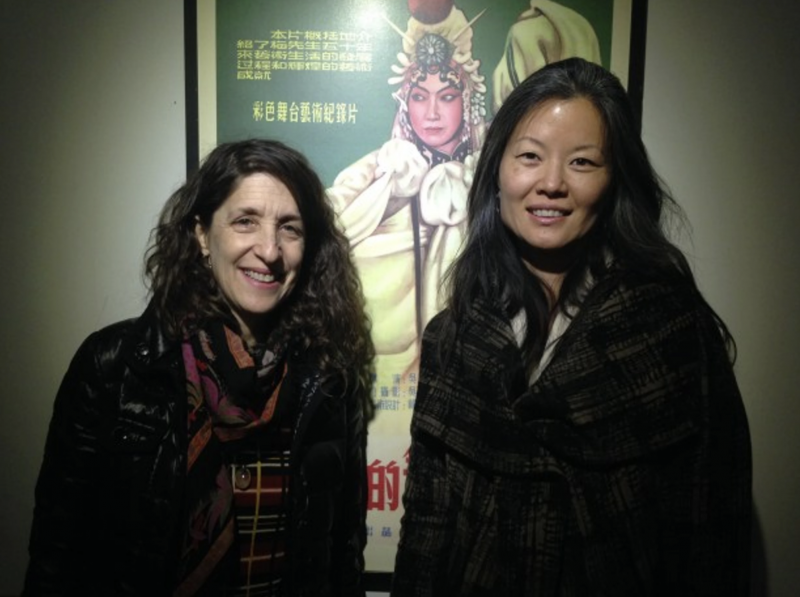

Posing with Lynne Sachs at CWFF’s opening ceremony. Lynne is the festival’s “filmmaker in focus.” Lynne’s latest film YOUR DAY IS MY NIGHT, and many of her earlier works, were subtitled into Chinese for these screenings. Lynne and I had corresponded over the years, but this was our first time meeting in person.

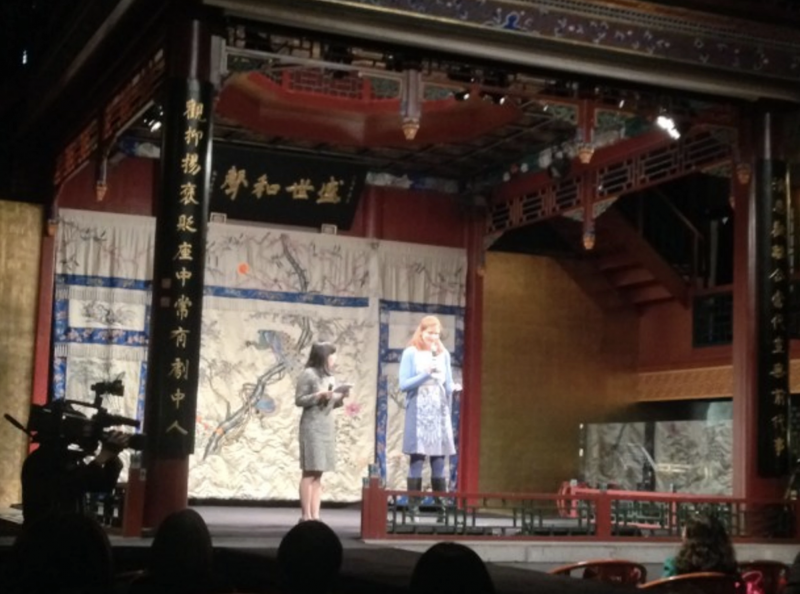

On stage at the Zhengyici Peking Opera Theatre. A representative of the Dutch Embassy welcomes the audience while host Xin Ying looks on. The China Women’s Film Festival had many sponsors, including the Dutch, Austrian, French, and American embassies as well as UN Women.

The official poster for the 2nd China Women’s Film Festival pays tribute to Esther Eng, the first female Hong Kong director and the subject of the festival’s opening film, S. Louisa Wei’s GOLDEN GATE GIRLS. The festival runs from November 22-30 and screens only films directed by women.