The National Gallery of Art presents

American Originals Now: Lynne Sachs

Sundays, Oct. 16 & 23, 2012

Category Archives: SECTIONS

An Open Conversation on Cultural Boycott of Israel

An

Open

Conversation

on

Cultural

Boycott

of

Israel

All are welcome!

Thursday, September 15, 2011; starting promptly at 7:30 p.m.

Kolot Chayeinu/ Voices of Our Lives: Building a Progressive Jewish Community in Brooklyn, 1012 Eighth Avenue @ 10th Street in Park Slope

You are invited to a respectful and open discussion that begins with a panel of Jews who have many different perspectives about cultural boycott of Israel. During this time when the UN is scheduled to vote on Palestinian statehood, we hope to encourage discussion and thought within the Jewish community about how to best support movements for peace and justice in Palestine/Israel. This evening will provide an opportunity to hear from people with different points of view about whether cultural boycott is an appropriate and effective strategy for doing just that.

Too often these days open discussions among American Jews about Israel, its politics, culture, and government are prevented, often from fear that differences may split apart a community, an institution, or friendships. This open conversation is a way to open up discussion, not shut it down.

Background: Many artists and musicians and others oppose the Israeli occupation and support the cultural boycott of Israel–which is part of the international Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaign—as a non-violent way to press Israel to abide by international law and recognize Palestinians’ human rights and right to self-determination. This boycott includes the decision not to perform or exhibit in Israel or in settlements in the Occupied Territories. This also includes a call to boycott Israeli institutions that are complicit with the occupation. Supporters of BDS and of cultural boycott have joined an appeal called for by Palestinian civil society asking the international community to use this nonviolent tool at a time when the Israeli government, as well as the U.S. and European governments, have failed to act to stop the abuses that are intensifying and when other forms of pressure have not been successful.

Other artists, actors, and musicians and others, also committed to peace and justice, feel differently. They believe that a cultural boycott of Israel does more harm than good and is not an appropriate tool in the Israeli-Palestinian context. They accept—or support accepting—invitations to perform or exhibit in Israel and prefer to keep channels of communication open. When Israeli cultural institutions or artists perform in the US, some of these people prefer to focus on their art, and not to engage in political action such as protests or calls for boycott. Some who share this view about cultural boycott also feel this way about the Palestinian call regarding BDS in general or other specific expressions of it.

The event: On September 15, we are fortunate to hear speakers who have thought deeply about—and been involved in—issues of peace and justice, who have spent time in Israel/Palestine, and who disagree with each other about BDS and cultural boycott. Some of our speakers are active in the arts, and some are members of Jewish groups that focus on peace in the Middle East. Some are members of our host congregation. Our moderator will encourage the speakers and audience to probe deeply into these issues and the many questions that arise as we think and talk together and learn from and listen to each other. There will be time for audience members to ask questions and engage in discussion as well.

Speakers (organizational affiliation for identification purposes only): Udi Aloni*, Filmmaker; Dalit Baum*, Who Profits?; Jethro Eisenstein, Board of Directors, Jewish Voice for Peace; Roy Nathanson, Musician, member of Kolot Chayeinu/Voices of Our Lives; Lynne Sachs, Filmmaker, member of Kolot Chayeinu/Voices of Our Lives; Ron Skolnik, Executive Director, Partners for Progressive Israel (Meretz USA)

Moderator: Esther Kaplan, radio and print journalist; editor of The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute; co-host of Beyond the Pale, which covers Jewish culture and politics on WBAI/New York

*The two Israeli speakers confirmed their participation prior to the July 11 passage in the Israeli Knesset of the “Bill for Prevention of Damage to the State of Israel Through Boycott.” This law, which has drawn widespread international criticism, limits freedom of expression and association and exposes Israeli citizens and organizations to litigation and penalties if they publicly call for all kinds of boycotts of Israel, settlements, or the occupation. Both speakers have once again confirmed they will join us.

Kid on Hip, Camera in Hand Interview with Lynne Sachs

http://kidonhip.com/films/photograph/lynne-sachs/

Interview with Lynne Sachs

Can you talk a bit about your background and what led you to filmmaking?

As a girl, I always loved to paint and write poetry. Since I had never

seen an experimental film, I had no real desire to create one. Then I

happened to stroll into some films by Marguerite Duras and Chantel

Ackerman in Paris when I was about 19. Like a flash of lightening, I

discovered there was a place where I could put all of my ideas about

images and words in a non-narrative vessel that had no formula other

than time.

Can you talk about a moment, a film, a screening that really

inspired you to become a filmmaker?

Looking back on the influential films I saw as a child, I think I

should mention “Finian’s Rainbow” by Francis Ford Coppola, “Billy

Jack” by Tom Laughlin, “Walkabout” by Nicolas Roeg, and “Children of

Paradise” by Marcel Carne. These were movies I saw as young person

that turned my world upside-down. “Billy Jack” is an intense, very

political, very macho, kind of hippie movie that I am embarrassed to

say so rocked my world that I went to see it about five times when I

was ten years old.

What is the genesis of “Photograph of Wind”?

One spring afternoon in 2001, I was standing in my backyard watching

my daughter Maya playing in the grass. As I stared intently at her, I

realized that my relationship to her fleeting youth was somehow

similar to that of my teacher Gunvor Nelson’s with her own daughter in

her film “My Name is Oona” (1969). In this film, Gunvor stares at Oona

who is riding with blissful abandon on a horse at the beach. Oona is

free to run with the animal wherever she may choose, and yet she is

somehow lovingly reigned in by the gaze and concern of her mother.

Through the fabric of the celluloid in both its clarity and its

obscurity Gunvor weaves an intimate, oneiric homage to her daughter.

On the soundtrack (recorded with Patrick Gleason and inspired by

American composer Steve Reich), she creates a musical litany made of

the sound of Oona speaking her name over and over. Perhaps it was

seeing this film that compelled me to pull out my 16mm camera to film

my daughter running as many circles as she could before falling

dizzily to the ground. I called this short cine-poem “Photograph of

Wind” (2001).

What were some of the film’s influences?

I was very influenced by the films that Robert Frank made of his own

children. I am not sure where he wrote this but somewhere he used the

expression “photograph of wind” and it spoke to me in a profound way.

Can you elaborate on the process of making the film? How

important is the process to you?

Sometimes I make very complex collage films. This is just the

opposite. “Photograph of Wind” is a very spare work that combines two

shots. In these two images, we see the collision of black and white

and color, a human being and the leaves of a tree. But in the

juxtaposition, I think we witness the sense of a fleeting childhood

and the last moments of summer. No matter how tightly we grasp the

moment, it will go away.

Can you contextualize “Photograph of Wind” in relationship

to your body of work overall. Does this film relate to themes that you

typically explore or is this film a departure?

I have been exploring women’s experiences through so much of my work,

going back to my first short film “Still Life with Woman and Four

Objects” (1986). I like investigating my own discoveries about my

life – from getting my period, to having children, and all the things

in between. Specifically, I have made about five films with my

daughters. We all enjoy diving into the creative process together.

How does your point of view as a mother and a woman inform your

filmmaking? (Some women have felt that if they were to be taken

seriously as filmmakers they had to be “closeted” mothers or choose

between the two. Is that something you have encountered?)

Being a mother makes me feel like I can run outside to look at a

flower bursting from a branch – carrying a camera or dragging along

one of my children – and I have an audience with whom to share the

experience. On a more somber note, I also made a film about an

Israeli mother and filmmaker who was killed with her children in a

political conflict. The film is called “States of UnBelonging” and

making it allowed me to explore what it means to take risks as a

mother and an artist.

Does your role as a filmmaker inform how you see yourself as a mother?

I think that by being an artist, and in my case a filmmaker, we can

share an excitement about making things with our children. Life feels

like a universe of possibilities, and the measures of success are not

so much commercial as personal.

Did you have reservations about including your kids in the

project? Can you share a story about the process of working with your

kids?

I did not have reservations. Making this film with my daughter was

just a continuation of our play – at least for her. For me, of

course, I had to spend days in the optical printing room transforming

the original footage into the dreamy, high-contrast motion you see on

screen.

How do you balance teaching, making films, your family, life,

etc? Can you share a day in your life doing this balancing act?

I am not sure I have found a balance, but I guess that I try to

translate the joy I have for teaching to my relationship with my kids.

Both are oriented toward young people of course, but my students just

stay the same age and my daughters grow up. The hard part is not to be

too much of a teacher with your own children.

We have shared the rationale behind putting together the Kid on

Hip program. Do you have any thoughts on being included in this group

of films as a screening program?

Truly honored.

Experimental TV Center presents Sachs & Street at Anthology Film Archives

In 2001 and 2003, I traveled to Owego, New York for a one-week residency at the ever-so-inspiring Experimental TV Center, a funky brick loft in a small upstate village where artists have been living and making video work for forty years. While there, I created images for my films Investigation of a Flame, Window Work and much later XY Chromosome Project, a collaboration with my partner Mark Street.

TRIBUTE TO THE EXPERIMENTAL TELEVISION CENTER

An evening showcasing the amazing video art created at ETC over the decades from 1970-2007.

Friday, July 15th – 7:30pm

Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue New York, NY 10003

The Experimental Television Center is a unique video art production studio in Owego, NY. Since its founding in 1971, ETC has been providing artists with access to the tools of video art production through residencies and grants. The studio includes several one of a kind pieces of video processing equipment including a custom-built Dave Jones Colorizer and 8 Channel Video Sequencer, the Paik/Abe Raster Synthesizer or ‘Wobbulator’ and a custom Dan Sandin Image Processor, among others. This month, after over 40 years of service in the media arts field, directors Ralph Hocking and Sherry Miller Hocking are retiring and closing the Center down. The Standby Program’s has selected this program of videos from 1971 to 2007 that were preserved through their ETC Preservation Program.

Program :

XY Chromosome, Lynne Sachs & Mark Street, 2007, 12:00 min.

An impressionistic odyssey for the eyes becomes both haunting and delightful in this moving image dream expedition.

“Sachs and Street engage in visual and aural dialogue to explore the spaces between abstraction and representation. Street’s inexhaustibly tactile images use handpainted found footage and camera-less films like luminous palimpsests before the eyes. Sachs responds with theatrical, microcosmic worlds where the everyday is defamiliarized through hundreds of trembling and resonating objects.” (Flavorpill.com)

with:

We Can’t Go Home Again, Nicholas Ray, 1970-72, 4:00 min. (excerpt)

Earth Pulse, Gary Hill, 1975, 5:35

etc, etc, Caspar Stracke, 2005, 6:08

Lake Affect, Jason Livingston, 2007, 1:13

Delta Visions, Shalom Gorewitz, 1980, 5:02

Bug-Eyed Ramrod, Matt Schlanger, 1984, 5:48

Transmigration, Julie Harrison & Carol Parkinson, 1987-89, 10:15 (excerpt)

Gender Rolls, Connie Coleman & Alan Powell, 1987, 3:21

Godzilla Hey!, Megan Roberts & Raymond Ghirardo, 1988, 2:20

Dirt Site, Alex Hahn, 1990, 15:53

Wax or the discovery of television among the bees, David Blair, 1991, 13:33 (excerpt)

Red M&Ms, Bianca Bob Miller, 1988, 3:51

MIT Press OCTOBER / Roundtable on Digital Experimental Cinema

Flo Jacobs, Ken Jacobs, Luis Recoder, Lynne Sachs, Mark Street, Malcom Turvey, Federico Windhausen

Roundtable on Digital Experimental Cinema

Published Summer 2011 by MIT Press

Malcolm Turvey: We are here to discuss the various ways digital technologies have, and have not, impacted experimental filmmaking. There was a time, in the mid-1990s, if not before, when some people argued that digital technologies were revolutionary and that they would fundamentally change filmmaking. Now that the dust has settled, or at least started to settle, and we can look back over the last fifteen or twenty years, the “digital revolution” might not seem like a revolution at all. We want to talk about both what has stayed the same and what has changed in experimental filmmaking thanks to the advent of digital technologies.

Ken Jacobs: I think those people were right, but they were premature. They first made that argument about analogue video. But analogue video was not the way. There were people, like myself, who saw it as a great but transient medium. We saw good things being done, but now those things have gone.

Turvey: Are you talking about video art?

Ken Jacobs: Yes.

Federico Windhausen: When video art emerged, was it being discussed as something that experimental filmmakers would have to address? I have always had the sense that experimental filmmakers in the era of analogue video art felt that they could keep their distance from it pretty easily.

Flo Jacobs: That’s because the film-developing labs were still functioning.

Windhausen: So it wasn’t a threat? It was something you could easily avoid?

Ken Jacobs:That’s right.

Windhausen: Do others recall the situation the same way?

Mark Street: I remember the discussion about who was a video artist and who was a filmmaker, and how they had different purviews. You said the advent of analogue video art-so you’re talking about the early 1960s?

Windhausen: The moment of wider dissemination of the technology in the late 1960s and ’70s.

Street: In the 1980s, when I went to film school, there was still that distinction, but it started to mean less. People were making choices about shooting on analogue video based on economics, not based on content or aesthetics. When I first went to film school, people would ask, “Is it a film, or is it a videotape?” But ten years later, it didn’t seem to matter as much.

Windhausen: Were you around when Canyon resisted distributing on video?

Street: Well, some at Canyon resisted and some didn’t. There were some who felt that video was a threat, as you say, and there were younger people who felt that it really didn’t matter what medium was being used, that what mattered was the work itself. I remember being pulled both ways.

Flo Jacobs: Don’t you think the change really occurred when cheaper editing soft-ware like Final Cut Pro became readily available? Before that, there was Avid, but Avid was expensive. Then Final Cut Pro changed everything.

Turvey: When was that, Flo?

Flo Jacobs: 1999.

Windhausen: Right around the time that cheap digital cameras came on the market.

Lynne Sachs:I think that was a revolution in terms of access. Because of its accessibility, more people could enjoy the freedom of using the new media for creative thinking. People started to believe you could be a “filmmaker” without being a “director,” and that making a film could be an autonomous act from start to finish, as painting and writing are. That was very radical, because before that, there was a hierarchy in filmmaking (except among experimental filmmakers who tried to work outside that hierarchy). I think there has been a very important shift in society’s understanding of filmmaking. People realize that the resources are there to do it individually. This “democratization” is not just a political shift; it’s a paradigmatic shift in that it allows filmmaking to be the product of a truly individual vision, as Stan Brakhage and others always advocated.

Windhausen: But hadn’t the Bolex 16mm film camera already enabled a lot of what you’re talking about? It facilitated a shift from thinking about becoming a director within the industry to thinking about oneself as a creative artist working individually outside the industry. The difference in the digital era is that there’s already a long history of experimental filmmaking, and that history has valorized and legitimized the notion of the individual film artist that you are talking about, whereas when the Bolex emerged, people like Maya Deren in the 1940s had to stake their claim to being a film artist.

Street: There’s another history at work too, and that’s the history of video art, which is a half step toward what you are talking about. Because analogue video was a popular, anti-high-art medium, it spoke to the idea that you could own your own camera and respond to television and things like that.

Ken Jacobs: The first video cameras were pricey-they weren’t that inviting. I remember one thing that shocked me was their low resolution. Ralph Hocking ran a video center, a lab upstate, and in his own work he consciously exploited video’s “low-res” rather than imitating film.

Sachs: The shame of the digital world is that as the machinery gets more and more advanced, there is an attempt to mirror reality as closely as possible. That is what I think is so disturbing, whereas the avant-garde is not trying to mirror reality. We’re trying to shape, investigate, play with, and sculpt it. High-definition is so unappealing to me because of that.

Luis Recoder: You used the word “sculpt,” and I think that film is becoming more of an art because of these crises. The digital wants to emulate film, and it is in a crisis: it doesn’t have a history. While that is going on, filmmakers like myself can work with film in a way that maybe you weren’t able to at one time. It’s a different kind of a possibility, I think.

Turvey: Do you mean that digital technologies show filmmakers ways to use celluloid that they might not have thought of before, ways that emphasize film’s differences from high-definition digital video?

Recoder: Yes, filmmakers and projection artists can work with celluloid in ways that are highlighted and assisted by this crisis, rather than evading or negating it.

Sachs: What do you mean by “crisis”?

Recoder: Well, you were saying that you’re not crazy about high-definition, right? I’m not crazy about it either. For instance, when you go to a film festival and bring your video, you don’t know what it’s going to look like when it’s projected, whereas with film, you have a better idea of what it’s going to look like and you can work with the projectionist to get it right. Video artists can sometimes do the same thing. They can run tests to see the quality of the projection. But often, you take your video to Sundance, or international film festivals, and it’s a bummer when you see it projected. With the medium of film, you have more control. I mean, you can even bring your own projector!

Ken Jacobs: I disagree. I can’t imagine a level of control over film that compares to the control you have with video.

Flo Jacobs: Except that you had fantastic problems switching over to PAL and Progressive Scan. You had disasters.

Ken Jacobs: Yes, there were problems. But let’s not forget the computer. It is this fantastic brain that can do anything. It gives just incredible freedom and control.

Sachs: For a while, one was totally dependent upon institutions in the city to convert from NTSC to PAL. But these days I can do much better conversions using Final Cut Pro and some other compressors than they can do. It takes a little while, but it looks perfect, going from PAL to NTSC or the other way.

Windhausen: But you’re talking about the advantages of video in production and postproduction, while Luis was talking about control over projection enabled by film.

Ken Jacobs: But there is a forward momentum with digital video, an urgency that’s lacking with film, which is just dying. There are only two film-processing labs in the city now. These problems with video will cease to be problems after a while. Video is constantly improving.

Flo Jacobs: But the other problem with digital video is preservation. What’s going to happen in ten years?

KenJacobs.The labs tell us that the only way to preserve digital video is to put it on film-on 35mm. [Laughter.]

Sachs: There are also the changes in our thinking brought about by these new technologies. The practical changes they occasion are a big part of our daily lives. But the changes in our thinking are harder to grasp. The other day, I was watching experimental documentaries by students from UnionDocs, and I asked them a question about sound, and every single student had downloaded their sound from the Internet. For them, it wasn’t about listening, about the surprise of finding something in the world around you. Instead, they seem to want to work in a cleaner comfort zone. Of course, we all work with found footage, and I adore that. But the surprises that come from working in the field teach you something about who you are in the world. I asked these people, who are all in their early-to-mid-twenties, if they ever go out into the world to listen to and record sounds. Their answer was no, for the most part. For them, filmmaking is more about acquiring the world than engaging with it.

Windhausen: Mark, do you find this with your students?

Street: I can make an analogy with books. I was talking to a student the other day and I said: “You’re looking for a book and it’s in the intellectual vicinity of these other books, so you go to the library to look for the book, and if the book isn’t there, there might be other books close by that could be of interest.” But it was an alien concept to this student-the idea of wandering and browsing and letting the library take you where it will. Nowadays there really is a more acquisitional approach to sound and images. It’s more like “I’m looking for this; let me go and get it” rather than “I’m going out to shoot and maybe I’ll happen on something by chance.” I think that’s a weakness of the digital age.

Ken Jacobs: They live only in their own times. They are not listening to the world, just making something out of the computer.

Turvey: Hold on. Isn’t it possible to discover something by chance on the Internet as well?

Sachs: That’s what they said to me. They said, “We find the most amazing things on the Internet,” and I said, “Oh, I spend plenty of time on the Internet, I know!” But they think: why go listen to the birds if you can download all these bird sounds without even knowing which birds they are?

Turvey: Lynne and Mark, if I understand your work correctly, you use multiple formats to shoot on, right? Do you do so because each medium offers different possibilities or advantages?

Street: For me, yes. I was in the basement today looking at a 16mm print that Craig Baldwin sent to me. I had to go downstairs and thread up the projector just to look at it, and there are limitations involved in that, just as there are limi- tations involved in shooting 16mm and Super 8mm film. I try to let those limitations speak, while also enjoying the freedom of the digital age. These days I transfer everything to digital, so I feel I can go out and shoot a roll of film and it’s OK to be defined by that roll for two minutes and forty seconds. But then I transfer it to digital and that opens up other possibilities.

Ken Jacobs. What moves you to still shoot film?

Street: I like the texture of it; I like the fact that when you shoot a roll of film, it becomes a specific entity and it’s unlike any other thing. It has its own weight and characteristics. You know? Thirty-six exposures: a roll of still film becomes like a little narrative, a little vignette of sorts. And I think that’s use- ful. I remember when I first started shooting videotape, I would fall asleep looking at my footage. [Laughter.] There was so much of it. I had six hours of footage. It used to be I had two rolls! You’d made it work, you’d make it count. So I like those limitations, I like being hemmed in, because making work is always about overcoming the obstacles.

Turvey: You are also interested in 35mm film, right? That’s fairly unusual within the experimental-film world. Didn’t you use 35mm film trailers in Trailer Trash [2009]? Where does that come from, that attraction to 35mm?

Street: Well, for a very brief and misguided period of time, I thought I could circumvent the fact that 16mm was disappearing in the early 1990s. I made a film called Sliding Off the Edge Of the World [2000] in 35mm in the hope that I could maintain the purity, such as it is, of the filmgoing experience. I was motivated, in part, by the experience of trying to show my films on 16mm. I would pay for a 16mm print and spend a lot of time and money figuring it out, only to be asked: “What’s that?” or, “Don’t you have that on tape?” Or to be told: “The projectionist is not here.” So I made a few 35mm films, and as I worked at a lab, it was easy for me to do that. However, Trailer Trash was finished in mini-DV, and I don’t really have any desire to work in 35mm anymore.

Windhausen: Ken, you did a couple of found-footage films on 35mm as well, right? Is it Disorient Express [1996] or Georgetown Loop [1996] that’s available on 35mm?

Ken Jacobs: Both are.

Windhausen: For the size of the image, because they are widescreen?

Ken Jacobs: That’s right. I hear what you’re saying about the intensity of using film. It costs so much, the meter is always running, and I honor that. But I enjoy having too much stuff on video, and then looking through it and seeing what unexpected thing I find, something I just couldn’t plan.

Turvey: So you find the extra volume of material facilitates creativity and surprise?

Ken Jacobs: I look at that stuff the way you might look at the world with a film camera. You pick it up from the world, but I’m looking at this already-recorded stuff to see what’s there that can suddenly be made vital.

Turvey: Luis, if I understand your projection process, you use 16mm film exclusively,is that right?

Recoder. And 35mm.

Turvey: You are from the youngest generation of filmmakers in this room, and so that means you would have gone to school in the 1990s, would that be right?

Recoder: Yeah, mid-’90s.

Turvey: Can you say something about why you work with celluloid film?

Recoder. I think it has a lot to do with what Lynne said earlier about the availability of media. Digital made celluloid film more available. You can now find it in a flea market for really cheap. I entered filmmaking at that moment in the mid-to-late-’90s when the hierarchy between celluloid film and digital wasn’t there. I didn’t have that kind of baggage, the view that one medium is more authentic than the other. It was more about availability and economic factors. Working with a projector and found footage, by chance I became a projectionist. I was going to festivals and was invited into the booth to set up my projector, and I learned about projection that way. I discovered possibilities within the realms of the theater and the booth, and the division between what’s hidden and what’s not, the apparatus and the audience. So it was really a schooling through the rear end of cinema, through the projection booth, which happened by chance. It wasn’t that I wanted to make films; it was more that I was led into it.

Windhausen: Guy Sherwin says that as well-that you can now buy film projectors really cheap. For him, digital has made it easier to work in film projection and performance than it was before, because you can just go on eBay and buy all these cast-aside film projectors that nobody wants anymore. Luis, you’ve been appearing at what I assume are expanded-cinema festivals. Have you seen other artists at these festivals working in video in ways that run parallel to, or in interesting contrast with, what you do in film?

Recoder: Not as much,but there are a few people working with old analogue video equipment from the ’70s, so there is a revival, a backwards gaze at the medium of video itself. I think it’s because it’s so hands-on. Even in music there is a revival of the old analogue hands-on process. It’s all due to performance, the desire to perform with the medium. Earlier, I used the word “control,” but really I think it’s an improvisational process. There’s control in the sense that you know what different things are going to do, but then the performance opens that up into messier, less controlled ways of working with the material.

Windhausen: So in your experience of going to these festivals, there has been a revival of expanded cinema largely in the photochemical-film and analogue-video modes, but not so much in the digital-video mode?

Recoder: I haven’t really seen digital video, but I’m sure it exists, more so in the art world than in the film world. At film festivals-not just at expanded-cinema events but also traditional film festivals-they are opening up spaces for installation art and performance, and my partner Sandra Gibson and I fall into that niche. A lot of festivals, even big ones like Sundance, want to highlight materiality. In a strange way they are becoming “structural materialists,” albeit unconsciously. They invite us because they want materiality, again due to the crisis occasioned by digital media. With digital media, there is nothing material to see or touch as a medium.

Sachs: I think one of the interesting directions that the digital world is taking us toward is a fetishism of decay. We miss decay, so we have to create the activity of something physical breaking apart or aging. In the world of architecture they create furniture that looks faux-worn and antique. It is very peculiar to me that there are digital effects that can create scratches and dust. We don’t want things to age. Nevertheless, we miss the chemical reactions, the fact that physical things change, so we simulate decay. It’s so strange. The desire for decay is a nostalgia for the aura of the original and its physical transformation. In digital, the original isn’t transformed, but we want it to be. I don’t necessarily aspire to this myself, but then I find myself including things like the flash-out flames, and I use found footage because it adds a texture that gives me so much delight. I think it does the same for the audience, who say, “Oh, I really like that,” because it doesn’t look realistic, it doesn’t look like television or digital video. That’s why there’s a desire for decay.

Windhausen: But it’s also a desire for the material markers of the filmstrip, as in the simulated end-of-roll light flares you now see in those spots for the Sundance channel. Things that experimental filmmakers first discovered about film or liked to reveal to an audience are now so easy to achieve digi- tally.

Street: But isn’t it a nostalgia on the part of the younger generation for something that never existed? The great “experimental” filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola said that he has no hankering for film. He lived it, but his daughter who didn’t live it, Sophia Coppola, wants to shoot on film all the time. I used to have this idea that you could go out and get projectors, Dumpster-dive, buy stuff on eBay, etc., and create a DIY punk film aesthetic. Then a student brought in an old camera, a regular 8mm camera, and it was rigged in a weird way with a funny magazine, like a regular 8mm magazine that you would pop in. I had never seen anything like it, so we poked around on the Internet and discovered you could buy those magazines through a Web site. There was a guy in L.A. who was tinkering with and remaking them and then selling them for $70 or $80 each. I realized there was something faux-nostalgic about this. It wasn’t about finding the detritus of the culture and using it. Rather, it was about re-creating it, in an anachronistic way, like wearing a pince-nez or jodhpurs or something like that.

Turvey: So decay and obsolescence have become commodified and cliched?

Street: That’s how I felt, that people are paying too much for these things. Why not just use a video camera that’s cheap and that’s the lingua franca now, you know?

Ken Jacobs: But the marks of these older technologies mean something. They ring a bell, they do something. I studied decay, OK? My Tom, Tom, The Piper’s Son [1969-71] is really about decay, among a lot of other things. It wasn’t about nostalgia, it was about asking, What is this old stuff? What is it made of? What is its character as a series of light impressions?

Windhausen: There is a video by the artist Cory Arcangel called Personal Film [2008], which is full of the effects you are talking about, but he made it on a desktop digital imaging program and had it transferred to 16mm film. It has flame-outs and scratches and count-down leader, and when you look at it in the installation space-it was at Team Gallery a couple of years ago-it’s a 16mm projector projecting a 16mm film. If you don’t read the text about it, then you don’t know that it was all done on a digital desktop. For better or for worse, he’s someone whose work reflects how that younger generation works with digital imagery.

Ken Jacobs: But that’s to make nonsense out of this stuff. The flameouts-I kept them in my films for a number of reasons. I wanted to say, “This is the end; I can’t shoot anymore, because I have no other roll of film.” But I also wanted to say, “This is film; this is the character of film. What I’m showing you are unedited rolls from a camera; I left the flash frames in”-that was part of the statement. And now you can make it happen digitally, and it doesn’t connote anything. It doesn’t signify. It’s just an effect.

Sachs: That’s why I think that the flash-frame only exists as a conceit, as a metaphor. It’s no longer indicative of something material.

Windhausen: Luis, you choose not to show your audience what you’re doing in terms of the photochemical film processes and the projection processes that you’re working with. What’s your sense of how they understand the images that you’re creating, given the lack of knowledge about photochemical film that we’ve been talking about. Do you care?

Recoder: Yeah, I do.When I started doing projector performances,a lot of the people who came to see the show were let down because there was no performance in the traditional sense. I wasn’t in front of the screen doing things. Nowadays, when you are talking about expanded-cinema shows, that’s what they expect-there are a lot of younger artists putting projectors in front of the audience and in front of the screen, so that you can see what they’re doing and can see the effects of what they’re doing. I try to work with the audience’s anticipation of this kind of performance and their subsequent disappointment, where the whole spectacle maintains itself as an illusion and then breaks down. The audience is confused about what they’re really seeing and what’s really happening. Is it film? Is it video? I work within the space of that confusion.

Windhausen: But does what you’re doing remain, then, a mystery for the audience?

Recoder: Slightly. We reveal it sometimes afterwards, during the Q&A.

Windhausen: Ken, at times you have shown audiences what you’re doing and at times you deliberately hide, or stand in front of, the apparatus.

Ken Jacobs: That’s only with the Nervous Magic Lantern. I don’t want people to think that they understand it because they see its parts. It is completely mystifying to me, doing it, and I don’t want an easy answer for them.

Windhausen: Do you care whether they think they see a film performance or a video performance? Some of my students get it wrong if they don’t see the apparatus.

Ken Jacobs: No, I don’t care. I don’t want them to think that they’ve seen video, although I’m not consistent. We were in Paris, and the interest in seeing the machinery was so strong, I just opened it up. I want people to realize that it really is a magic lantern. That’s all it is. The result is coming from these primitive means. To have someone think it’s video would be disappointing.

Now, some of it is being recorded on video. There is a DVD of a piece I did with John Zorn, Celestial Subway Lines/Salvaging Noise [2004], so I guess I don’t think that it’s always so important that one see the machine. I also want the effects onscreen to be appreciated for themselves.

Flo Jacobs: But you can’t record it at all; it’s impossible. Every time we rehearse, it’s different, no matter what you do.

Ken Jacobs: What Flo is saying is that each time I do it, I improvise. I can’t repeat what I did a previous time.

Street: I’m just wondering: if flash-frames are film ephemera and Joan Jonas’s vertical roll is early video ephemera, what are the ephemera for digital video? What do people show when they’re showing us the subconscious of the medium?

Windhausen:Ken shows artifacting, pixelation …

Street: Ernie Gehr shows the space between the frames, as in Crystal Palace [2002]. I guess that’s it.

Windhausen: What we’re talking about are the medium-specific gestures that are typically made when a medium emerges and artists want to see what are, for example, the unique artifacts of decay within that medium, or something like that, right?

Street: Right, things that remain particular and idiosyncratic to that medium.

Windhausen: Cameras these days are like computers in that they have built-in obsolescence, like laptops. After a certain number of years, a camera is going to be off the market and obsolete. You and Lynne still work with mini-DV rather than HD, so you’re already old-school. Ken, meanwhile, has moved on to high-definition (he’s the youngest of all of us). [Laughter.] Last year Ken had a Creative Vado High Definition handheld pocket camera, and now he’s already got a new one that I’ve never even seen before. It doesn’t even have a viewfinder or a screen! So the question becomes: why bother doing medium- specific work when your medium is obsolete within a year?

Ken Jacobs: Young people, I believe, are sampling. They encounter something, they get an idea, and then they go for something else. The idea of making a discrete work that begins here and ends there is passe.

Windhausen: At the Oberhausen Film Festival’s retrospective of his work this year, Fred Worden said something similar when discussing his newer work in video. Filmmakers can now continually revise their work, because they have it on a hard drive. You just look up a particular file and continue working on it. The open work is becoming more of a norm now.

Street: I think that openness is good. I always encourage my students-this is Final Cut Pro talk-to create a new sequence every time they sit down to edit, as if they are reinventing the film every time. Filmmaking was linear; it involved a progression. As you edited it, the film hopefully got better, shorter, clearer. But in the digital age, you can sit down on a Tuesday and reinvent your film and on a Wednesday reinvent it again; you are not bound by a linear progression.

Windhausen: You don’t have the point of termination of having to pay for the print, for example.

Street: There was also an investment in every one of your gestures. A splice had better be good, because it was costly to go back. But with digital, you can experiment and play around because nothing is irrevocable. Very few of my students take me up on that, though. It’s usually still one sequence that they invest in and keep trying to improve.

Sachs: There is a term used today, which is “non-destructive.” The way we work now is that everything is protected. You’re never really working with what you did yesterday but rather with a duplicate of it, so that if you don’t like what you do today you can always go back to what you did yesterday. But when you were editing with film, you didn’t have that freedom. You were working with a work print, and if you cut it, of course you could put it back together, but most of the time, if you did intricate cutting, you were going towards some- thing and you weren’t going to break up all those little frames again. It was essentially destructive; there was no return. But now we want the constant capability of returning to something as if we were striving towards perfection and any risk we take might lead us astray from that perfect end.

Ken Jacobs: Are you saying this is positive or negative?

Sachs:I don’t know. It’s positive because I’m used to it now, but I don’t know if it makes me more risk-averse or less.

Turvey: So if it’s so easy to alter and go back, how do you know when a film is finished? What is the criterion, now, for a finished film?

Ken Jacobs: Oh, wait a minute. That’s nothing new. One simply senses that it is done, just like with a painting or a poem or anything else. You step away and it’s done. I don’t think that’s changed. I want to say this: Kino’s Avant-Garde 3 DVD contains Danse Macabre [Dudley Murphy, 1922], The Petrified Dog [Sidney Peterson, 1948], Plague Summer [Chester Kessler,1951], TheDeath of a Stag[Dimitri Kirsanoff, 1951], Image in the Snow [Willard Maas, 1952]- all of these could have been shot on video. There are very few films that pertain to the twenty-four frames per second, or sixteen frames per second, of the film strand. It takes some of Brakhage’s work, or Kubelka’s, to say, “Yeah, that had to be shot on film.”

Windhausen: What about Wavelength[Michael Snow, 1967]?

Ken Jacobs: Wavelength could have been shot on video, too.

Windhausen: Snow might say that you go from a long shot to the close-up of the postcard with the waves, which is a pyramid-shaped trajectory, whereas the projection from the film projector to the screen forms an inverse pyramid.

Street: But doesn’t that concern projection rather than being shot on video? There is the distinction between showing something on a small screen versus a large screen, and the distinction between shooting something on film and video. For example,I saw Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce1080 Bruxelles [Chantal Akerman, 1975] at Film Forum, and I had only seen it on VHS on the small screen. When you see it big, it all comes together, and when you see it small, it’s nothing. It’s a question of kind not degree.

Ken Jacobs: Scale is enormously important. It’s the same thing with music. Scale is significant.

Windhausen: Interesting. So what you’re saying is that for a large number of experimental films, there is not much lost if you watch them on video?

Ken Jacobs: No, I am saying that there is nothing lost if you make them on video; there is if you watch them on a monitor.

Windhausen: Oh, OK. Now, related to this and to distribution issues, there seem to be more festivals showing experimental work now than ever before. So do you find that your work is being disseminated more than ever before? To what degree are the festivals more important or more prominent than exhibition venues like Anthology Film Archives? Also, none of you have films on the Web. None of you have Web sites where full, high-definition versions of your work can be seen. Why not? •

Ken Jacobs: I’m unhappy when things are shown in less than optimum conditions. It makes me very unhappy, and that’s why it’s really important to make hard copies. Hard copies exist when people really care about work, people who want to have a DVD or something.

Windhausen: And is more of your work being seen, not just at festivals but in venues that are interested in showing works by Mark Street or Ken Jacobs, now that they can find a DVD to rent?

Ken Jacobs: Yeah, and they can find us.

Windhausen: OK, so how many of you travel with your work? One of the core values

of experimental film is the temporary community of the theatrical audience, the people in the seats who are watching your film. If film exhibition becomes Web-based, you lose that temporary community, potentially. Is that something that you are reluctant to let go of? Do you care?

Street: I’m reluctant. When you’re in your house, you’re surrounded by the things that you love, that you bought-bourgeois trappings-and I think you’re less able to take risks. But when you go sit in a theater, there’s a social contract. I’m watching Jeanne Dielman, I’m bored, but I’m not going to get up. I’m going to stick it out because there’s a social contract and I’m part of the temporary community you mention. I have a film festival at the end of every semester with my students, and the students ask, “Why? Why do we all have to get together at 7 p.m. on a Thursday? Can’t I just look at a disc, can’t you just give me a disc? Is it going to be on the Web?” It’s a very telling, contemporary question.

Ken Jacobs: And when they look at a disc, they skip through the film, the fuckers. [Laughter.]

Street: I like the social part of it. I think it’s important to be in the same room with the work and experience it as a group in the dark.

Ken Jacobs: I disagree. It’s always just me and the work. I’m not even with Flo when I’m watching this thing. I’m with the person who conceived and presented it,just like reading a book. I’m alone. I don’t want people around.

Sachs: You asked about whether we travel with our work. I actually make a lot of effort to travel with my work, and it’s extremely disruptive to family life and work life. But it’s very important to me. It keeps it alive. It makes it human. Many times I am paid an honorarium but they say, “We want you to be here,” and it’s not very much money. Nevertheless, I do my best to go with the films if I can. It’s worth it to me to feel that aliveness the way musicians do, or the- ater people. It’s not as if my work is all over the place in stores and it has this productive presence in society.

Windhausen: I can imagine younger filmmakers thinking that Web distribution is fine because they will get feedback from blog comments or things like that. But I haven’t seen it. I still find that younger filmmakers want a body of peo- ple responding directly to their work.

Ken Jacobs:I would very much love for my stuff to be available. Free is OK with me, although every so often I realize that’s not realistic. We need the money, there should be some money coming back, but really I just want the work simply out there, and as good as it can be.

Flo Jacobs: What Ken really wants is to travel with live works, otherwise it doesn’t make any sense. It’s easy for him to just put a DVD in the mail, so the only reason to travel is to perform.

Street: For you, Luis, the DVD does not exist, right?

Recoder. No, we have DVDs. We like to have our work seen by as many people as possible, and not everyone can invite us, not everyone has those resources. Our work has been shown on DVDs in installations, at places where they couldn’t invite us to go and do performances. For me, the medium of digital video is irrelevant; it’s just another distribution format. What we do is not video art. Some people might see it that way,but that’s not really a direction that I’m interested in.

Ken Jacobs: I’m someone who really likes working with accidents, and to me, video is a vast accident, you know, unplanned, unexpected, wow!

Turvey: Can you give examples?

Ken Jacobs: Well, I work with these miniature digital cameras, and I can’t see through them. For years I worked without a reflex lens, and it was a major thing in my life when I could afford to buy one with a built-in viewer. These miniature digital cameras are cheap models, unbelievable models. They focus by themselves, they get the right light levels by themselves. You press a button to turn them on and another to take a picture. Yes, there is a lot they don’t do, but it’s so much fun exploring what they can do, much of which is unexpected. So, I’m really grateful.

Turvey: Ken, would you ever go back to shooting on film?

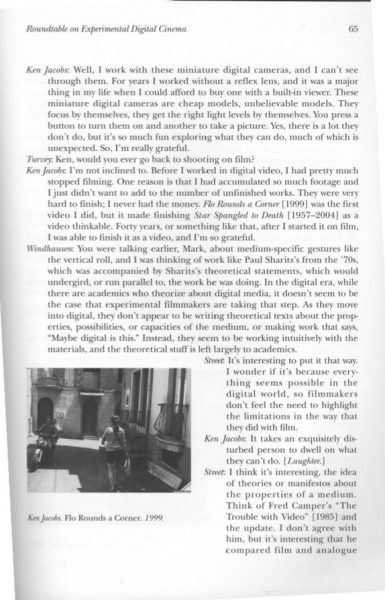

Ken Jacobs. I’m not inclined to. Before I worked in digital video, I had pretty much stopped filming. One reason is that I had accumulated so much footage and I just didn’t want to add to the number of unfinished works. They were very hard to finish; I never had the money. Flo Rounds a Corner [1999] was the first video I did, but it made finishing Star Spangled to Death [1957-2004] as a video thinkable. Forty years, or something like that, after I started it on film, I was able to finish it as a video, and I’m so grateful.

Windhausen: You were talking earlier, Mark, about medium-specific gestures like the vertical roll, and I was thinking of work like Paul Sharits’s from the ’70s, which was accompanied by Sharits’s theoretical statements, which would undergird, or run parallel to, the work he was doing. In the digital era, while there are academics who theorize about digital media, it doesn’t seem to be the case that experimental filmmakers are taking that step. As they move into digital, they don’t appear to be writing theoretical texts about the prop erties, possibilities, or capacities of the medium, or making work that says , “Maybe digital is this.” Instead, they seem to be working intuitively with the materials, and the theoretical stuff is left largely to academics.

Street: It’s interesting to put it that way. I wonder if it’s because every-thing seems possible in the digital world, so filmmakers don’t feel the need to highlight the limitations in the way that they did with film.

Ken Jacobs. It takes an exquisitely disturbed person to dwell on what they can’t do. [Laughter.]

Street: I think it’s interesting, the idea of theories or manifestos about the properties of a medium. Think of Fred Camper’s “The Trouble with Video~ [1985] and the update. I don’t agree with him, but it’s interesting that he compared film and analogue video. I don’t know that any filmmaker is doing that with digital. It’s too easy, in the digital world, to think that the latest thing is the new language and is not to be questioned. I see that right now with the 16:9 aspect ratio, for instance. It used to be that we had 4:3 or 16:9, that there was a choice. But in the last two years, I’ve noticed with my students that it’s not a choice any- more. They use 16:9, and that’s it.

Windhausen: So can we agree that the filmmakers here are relatively conservative in that they prefer to show their work in a theatrical projection situation where the temporary community of an audience has to watch the work from beginning to end?

Ken Jacobs: And you can’t go to the bathroom! [Laughter]

Windhauseri: That’s fairly conservative though, right?

Flo Jacobs: No, it isn’t! That’s not conservative.

Windhausen: It is today. You’re conserving it as a tradition. It’s a valuable tradition but it’s a conservative move.

Flo Jacobs: Do you want to walk into the middle of Strangers on a Train [Alfred Hitchcock, 1951]? I don’t think so. ls that being conservative?

Windhausen: I guess I mean new work.

Recoder: I think you can be more radically conservative now in the gallery. There are things that we are doing, my partner and I, that no theater is going to show. They are too long, or too boring, whereas in the gallery you can show them.

Windhausen: You’re making gallery work now?

Recoder.Yes.

Windhausen: But you’re in the minority here, is what I’m saying.

KenJacobs: All of us make work that begins at one time and ends at another time. We want it to be seen that way!

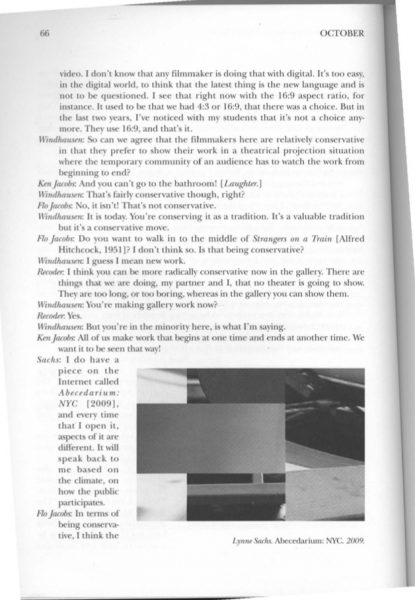

Sachs: I do have a piece on the Internet called Abecedarium: NYC [2009], and every time that I open it, aspects of it are different. It will speak back to me based on the climate, on how the public participates.

Flo Jacobs: In terms of being conservative, I think the work has to be seen from beginning to end. You can’t just stroll in, visit it, and stroll out. You can say the same thing about a painting. You wouldn’t want somebody to cut a detail out of a painting at the Met and hang that up, would you?

Windhausen: Well, there’s a difference between a perpetually open work and one that’s finished. I’m thinking, as a point of comparison, of new-media artists, who make work that’s interactive and continually open to change. It can be entered into and left behind at any point.

Flo Jacobs: But that’s their concept, that’s their work.

Windhausen:Another shift is that television is more cinematic, now, in every way, and people emulate the film theater in their homes.

Ken Jacobs:That’s good, because what about the kids who are looking at a cluttered monitor while watching a movie in bed?

Sachs: Or three movies!

Windhausen:”What’s wrong with that?” the kids would say.

Ken Jacobs:That’s right, they would say that. But they would not understand the problem.

Sachs:That is a real function of the digital, the fact that people believe that it is just as good an experience to watch more than one thing at once.

Ken Jacobs: Multitasking.

Sachs: Or multi-watching. It’s not even a task, because they’re not having to do something. It’s a “more is better” attitude.

Windhausen: In relation to this, I was thinking, Luis, that what I’ve seen at expanded-cinema festivals is a lot of work that is ambient, where I have the sense that the artist expects you to dip in and out of it in a relatively aleatory and arbitrary way, whereas what I’m accustomed to in single-screen theatrical, experimental films is having my attention be directed from beginning to end.

Ken Jacobs: OK, there was this guy named Andy Warhol [Laughter], and he introduced “background paintings” to convivial meetings, with people drinking and talking in front of something that looked expensive. That is a huge tradition now. I call it “stuntism”-fifty paintings of Marilyn Monroe or whatever. It’s not about asking people to learn how to see and to look at something very intently.

Turvey: But there are different kinds of work, right? So, obviously, your work demands and requires an intense perceptual engagement. But that’s not true of other kinds of work, or some television shows, or other things that one might consume on a smaller screen.

Ken Jacobs:T here are households where the TV is the first thing on and the last thing off.

Turvey: What I mean is that there are different viewing modes appropriate to different kinds of work. Just because people are watching three things at the same time on small screens doesn’t mean they are watching them inappropriately. For example, it would be foolish to sit and watch a CNN broadcast with the perceptual intensity that one would watch a work you make.

Ken Jacobs: Yes, I think we are what they call fascists. We want to dominate your complete attention.

Recoder: I think that’s what you were asking about, Federico, the aleatory, “in and out” perceptual experience of a certain kind of performance. Allowing that sort of open play and knowing that you have audiences who have all kinds of attention spans is to be anti-fascist, I think. And when you take out narrative and images, you are completely lost. One of the things that brought me to the avant-garde was the experience of viewing. I felt that I could walk in and walk out of it, not physically but perceptually. It allowed me to be in a space where there is a confusion between “Am I making this? Or is this making me?”

Windhausen: But you are articulating something very different from what these three filmmakers do in their single-screen works. Maybe you’re an exception, Ken, but most of the work that you’ve all made has a beginning, middle, and end, and you place a value on directing the viewer through the work. But with expanded-cinema pieces, as Luis has said, it’s the viewer making the work in an aleatory process that is equal to or of more value than being directed through the work.

Ken Jacobs: I don’t direct anybody. I am fascinated, and if I remain fascinated from beginning to end, that’s all the direction that goes into it.

Street: But Federico, there was ambient work that you dipped into and out of in the ’50s and ’60s. I don’t know that it’s technological.

Windhausen: It wasn’t the dominant mode. I’m talking about dominant modes within experimental cinema.

Street: So you think the dominant mode of experimental cinema today is aleatory?

Windhausen: No, I think it’s the dominant mode of expanded cinema.

Street: Right, but I think that’s a style, and I don’t think it’s any greater today than it was in 1969, or 1959, even.

Windhausen: Well, it’s certainly more popular today than it was back then.

Street: Maybe, but there has always been artwork that is non-directive, that allowspeople to engage it with various degrees of attention. It would be interesting to compare this new paradigm, as you describe it, to Christmas on Earth [Barbara Rubin, 1963], or something.

Windhausen: I’m not saying that those precedents don’t exist; I’m just saying that they weren’t as prominent as they are now.

Recoder: I’m interested in the word Federico used, “conservative.” I’m wondering where that’s coming from, as if you were trying to pin us all down.

Windhausen: I was talking about the theatrical situation with the temporary community and everyone looking at the same screen at the same time. That’s a long-standing value within the tradition of experimental film, one that I hope continues. But it is “conservative” from the perspective of the new-media artist.

Street: I’m conservative in that sense. I’ll sign.

Ten Short Film by Lynne Sachs at Austin Film Society

Avant Cinema 4.3: 10 Short Films by Lynne Sachs

Screening Info

Wednesday, May 25 at 7 PM

AFS Screening Room (1901 E. 51st St, Gate 2 by water tower)

$5 AFS Members & Students w/ Valid ID / $8 General Public

Q&A with Lynne Sachs via Skype, moderated by Austin experimental filmmaker/teacher Caroline Koebel

“Equal parts humanist and formalist, poet and historian, telling tales that are both timeless and political, Lynne Sachs creates film worlds in which the textures of daily domestic life are seamlessly connected to the realms of war, political activism, and our response to terrorist attacks. In one film, a grid becomes a secret map for understanding the difference between male and female. In another, an affectionate portrait of her young daughter becomes a study of whirling circular energy. For each of these ten shorts, Sachs creates a unique film language, by weaving together images, sounds, and words that evoke a particular way of viewing the world. All of these works reveal a sensibility that refuses to flatten either life or art, insisting on a multilevel reality in which the personal and the universal become doorways to a broader consciousness.” –David Finkelstein, writer for Filmthreat.com

This 62-minute program of ten films is made possible by Microcinema and their outstanding selection of experimental films presented in digital format.

‘Atalanta: 32 Years Later’ in Enchanted Brooklyn: Contemporary Fairytale Films / Brooklyn Arts Council

Enchanted Brooklyn: Contemporary Fairytale Films

Brooklyn Arts Council, BAMcinematek

May 9, 2011

https://www.brooklynartscouncil.org/events/enchanted-brooklyn

Enchanted Brooklyn takes a look at the evolution of the fairytale film, with classic stories re-invented by contemporary Brooklyn filmmakers.

Films by Georges Melies

Cinderella (Cendrillon)(1899), 6 min

Kingdom of the Fairies (1903), 16 min

Bluebeard (Barbe-Bleue)(1902), 9 min

The program begins with a look at the work of early film pioneer Georges Melies, who created spectacular fairytale films, the likes of which the world had never seen before. Fast-forward 100 years, to present day Brooklyn, where local filmmakers are re-imagining fairy tales and fables in new and experimental ways. Dr. Kay Turner, Brooklyn Arts Council Folk Arts Director, will be on hand to give context about the history and relevance of these magical, classic stories.

The Hunter and the Swan Discuss Their Meeting

Emily Carmichael, 8 min

A Brooklyn couple have dinner with a hunter and his girlfriend, a magical swan woman. It doesn’t go well.

Emily Carmichael is in many ways a Renaissance girl. As a Harvard University undergraduate she studied painting and literature, wrote and directed two full-length plays, directed a production of “Macbeth: The Puppet Shakespeare,” for which she designed and sculpted 22 clay puppets, and created the comic strip “Whiz Kidz,” which ran in the Harvard Crimson for two years. In 2006, she entered the MFA film program at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, where she has written and directed several live-action shorts and created the animated series “The Adventures of Ledo and Ix.” Carmichael’s films have screened at the Anthology Film Archives, Sundance, Slamdance, the South by Southwest Film Festival, and the CineVegas International Film Festival.

Atalanta: 32 Years Later

Lynne Sachs, 5 min

A retelling of the age-old fairy tale of the beautiful princess in search of the perfect prince. In 1974, Marlo Thomas’ hip, liberal celebrity gang created a feminist version of the children’s parable for mainstream TV’s “Free To Be You and Me.’ In 2006, Sachs dreamed up this new experimental film reworking, a homage to girl/girl romance.

Lynne Sachs makes films, videos, installations and web projects that explore the intricate relationship between personal observations and broader historical experiences by weaving together poetry, collage, painting, politics and layered sound design. Since 1994, her five essay films have taken her to Vietnam, Bosnia, Israel and Germany. Sites affected by international war where she tries to work in the space between a community’s collective memory and her own subjective perceptions. Strongly committed to a dialogue between cinematic theory and practice, Lynne searches for a rigorous play between image and sound, pushing the visual and aural textures in her work with each and every new project. Since 2006, she has collaborated with her partner Mark Street in a series of playful, mixed-media performance collaborations they call The XY Chromosome Project. In addition to her work with the moving image, Lynne co-edited the 2009 Millennium Film Journal issue on “Experiments in Documentary”. Supported by fellowships from the Rockefeller and Jerome Foundations and the New York State Council on the Arts, Lynne’s films have screened at the Museum of Modern Art, the New York Film Festival, the Sundance Film Festival and recently in a five film survey at the Buenos Aires Film Festival. In 2010, the San Francisco Cinematheque published a monograph with four original essays in conjunction with a full retrospective of Lynne’s work. Lynne teaches experimental film and video at New York University and lives in Brooklyn.

Fable in 3 Colors

Adam Shecter, 12 min

Borges states in his Book of Imaginary Beings that Hercules could not kill the Hydra’s last head. Instead, it was buried: immortal, dreaming, and hating. Filmmaker Adam Shecter began to wonder what the dreams of a myth would be. Fable in Three Colors represents the fusion of two types of mythology: the personal (dreams) and the cultural.

Adam Shecter is a visual artist and educator living in New York City. Working primarily in 2D animation and editions, his work is greatly influenced by mythology and mass cultural forms: from cinema to Saturday morning cartoons, comic books and music. He has had solo exhibitions of his work at Eleven Rivington Gallery (New York), Konstforeningen Aura (Lund), and Bielefelder Kunstverein (Bielefelder), among others. He attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2006. He has maintained his online test-site, theworldofadam.com, since 2001. His next show, “Last Men,” opens at the Eleven Rivington gallery this month.

The Queen

Christina Choe, 8 min

Bobby, a Korean-American teenage outcast, is working at his parent’s dry cleaners on prom weekend. When the prom queen and her boyfriend stop by with their dress and tuxedo, Bobby has his own prom to remember.

Christina Choe is a writer and director. She began her career as a documentary filmmaker and has screened her short documentary films, Turmeric Border Marks and United Nations of Hip Hop at numerous film festivals worldwide, including AFI Film Festival, Seattle, and Palm Springs Shorts Film Festival. In 2002 she received a New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship grant for video. She has also worked as an editor/assistant editor for ABC, VH1, HBO and the History Channel. Her feature script, “Guess Who’s Coming For Kimchee” was selected as the winner of the 2007 CAPE (Coalition of Asian Pacifics in Entertainment) New Writers Award for Best Feature Screenplay, the KOFIC (Korean Film Council) Filmmaker Lab, IFP Market Emerging Narrative Program, and placed in the top 20 for the 2008 Bluecat Screenwriting Competition. Most recently, she was also a semi-finalist for the ABC/Disney TV Writing Program. Her first narrative short, The Queen was selected as ‘Best of Fest’ at Palm Springs International Short Film Festival, Telluride, Aspen ShortsFest, Los Angeles Film Festival and nominated for the Iris Prize (UK Film Council). She is currently based in Brooklyn, where she is an MFA candidate at Columbia University for writing/directing and is working on a post-apocalyptic feature script about the future of food.

Fairytale Fragments

Li Cornfeld and Paul Snyder, 3 min

Red Riding Hood gets stalked. Beauty gets sold. Bluebeard gets cooked.

Li Cornfeld lives in Brooklyn, where she writes and teaches. Her current projects include a chapter in a forthcoming women’s studies anthology on folklore, feminism, and Hermione Granger, and an etiquette blog,www.civilshepherd.com.

Paul Snyder is a film, commercial and music video editor. He has had the privilege of cutting for Spike Lee, Brett Morgen, and his work with the directors LEGS has been nominated for VMA and AICE awards. Paul works with the editorial company Lost Planet.

ENCHANTED BROOKLYN: Contemporary Fairy Tale Films is part of BAC’s Once Upon A Time in Brooklyn: Traditional Storytellers and Their Tales, a series of public programs and workshops featuring Brooklyn storytellers practicing various genres including folk tales, fairy tale, ghost stories, saints’ legends, personal experience, spoken word, talking drum, narrative dance, and more.

Proteus Gallery / Paradise of Projected Light

Saturday, April 23 2011 at 7pm

A program of short films by Ernie Gehr, Stan Brakhage, Jeanne Liotta, Sam Green and Mark Street will be followed by a post-screening discussion with Gehr, Green and Street. The films, curated by Lynne Sachs, Mark Street and Erik Schurink splinter and refract our preconceptions about paradise. The line-up begins with Stan Brakhage’s 1960s elegy to the NYC subway as urban miracle and his later microscopic homage to the awesome simplicity of a leaf, a petal and an insect. Next, we focus upward for Jeanne Liotta’s celebration of all things starry in the cosmos. Ernie Gehr is next with This Side of Paradise, of which Village Voice critic J. Hoberman said, “To watch (Gehr’s) film is to journey into the underground ….When Gehr inverts his camera, the world turns up-side-down. Heaven and Earth change places. The mud above, the sky below – which side of Paradise, indeed?”

Next Sam Green will take us on a journey of 20th Century utopias – both sublime and failed. And finally we’ll follow Mark Street on a geo-poetic search for the home of NYC’s collage hero Joseph Cornell, a life-long resident of the borough of Queens’ very own Utopia Parkway.

After the films, filmmakers Ernie Gehr, Sam Green and Mark Street will join us for a discussion of their work in the context of Proteus’ year-long investigation of Paradise.

The program: The Wonder Ring by Stan Brakhage with Joseph Cornell (4 min., 1960); Mothlight by Stan Brakhage (4 min., 1963); Observando el Cielo by Jeanne Liotta (12min., 2007); Sweet Dreams by Jeanne Liotta (4 min., 2009); This Side of Paradise by Ernie Gehr (14 min. 1991); Utopia Part 3: the World’s Largest Shopping Mall by Sam Green (12 min., 2010); and Utopia Parkway by Mark Street (5 min., 2011).

Lynne Sachs’ first film in Chick Docs- I Hate You

The Film-Makers’ Coop: Chick Docs- I Hate You

Saturday, April 23 at 7:30pm

Union Docs

322 Union Ave

Brooklyn, NY 11211

Boredom, murder, dress-up, dress-down, the underworld and the inner world. Angry lost resigned women navigate you through a hormonal roller coaster with this collection of documents of events and emotions. This is a biography of the shadowlands of the female psyche, with no cause or apology. Curated from the Film-Makers’ Cooperative collection by Jasmine Hirst and Katherine Bauer.

I Was a Teenage Serial Killer by Sarah Jacobson

USA, 1993, 27 minutes, Digital Projection, Black and White

Mary was a good girl until she decides to kill all the “sexist pigs.” She of course encounters many, of which, and enjoys killing them.

Psycho Pussy Slaughter by Katherine Bauer

USA, 2007, 10 minutes, Digital Projection

The Egyptian Goddess Sekhmet is brought back from her long slumber on the wine of the Nile. She is defeated, shortly after sacrificing several felines and females in her bloody revenant rituals.

Trailers by Jasmine Hirst

USA, 2011, 30 minutes, Digital Projection, Color and Black and White

I met and filmed Aileen Wuornos on death row in Florida in 1997. We had been corresponding for 5 years when Aileen asked me to film her talking about the truth of her life and crimes as part of her preparation to die. I have

been trying to finish this feature length documentary since then. But can’t. There is something wrong with me. Instead I make two minute trailers about other films I’d like to make. This is a trailer of trailers.

Liar by Anne Hanavan

USA, 2006, 2 minutes, Digital Projection

Fourth in a series of sexually explicit self portraits where the artist works through issues surrounding her past experiences with sex work, rape, and Catholicism.

Heaven by Linda Dement

USA, 1986, 3 minutes, Digital Projection

Punk surreal darkness from the streets of early 1980′s Sydney; artist Jasmine Hirst eats diamonds, a dead pig’s eye is gouged out, a girl aims her rifle & shoots while a voice reads from Bataille’s “The Story of the Eye”

Still Life With Woman and Four Objects by Lynne Sachs

USA, 1986, 4 minutes, Digital Projection, Black and White

A film portrait that falls somewhere between a painting and a prose poem, a look at a woman’s daily routines and thoughts via an exploration of her as a “character”. By interweaving threads of history and fiction, the film is also a tribute to a real woman. – Emma Goldman, 1986

Trick Film by Lotta Teasin

USA, 1996, 6 minutes, Digital Projection

Activities at home with the Mistress and her naughty pet. Starring Y.B. naughty and Ima Bottom.

Death Love by Katherine Bauer

USA, 2011, 3 minutes, 16mm

A girl digs out of the earth what she has lost.

Double Your Pleasure by M. M. Serra

USA, 2002, 4 minutes, 16mm, Black and White

Sound by Jennifer Reeves. Part of the “Ad It Up” series of shorts that are parodies of commercials.

i hate you by Michelle Handelman

USA, 2002, 3 minutes, Digital Projection

Riffing off of Nauman’s early performance tapes, Handelman chants this negative affirmation into a song of personal endearment. Simultaneously self- reflexive, self-conscious, meditative and pathetically funny.

The Urban Landscape in Cinematic Transformation

THE NEW AMERICAN CINEMA GROUP / THE FILM-MAKERS’ COOP in collaboration with MILLENNIUM FILM WORKSHOP present:

THE URBAN LANDSCAPE IN CINEMATIC TRANSFORMATION

PROGRAM 1: SHORTS: SATURDAY, MAY 7, 7 PM PROGRAM 2: FEATURE: SATURDAY, MAY 7, 9 PM

PROGRAM 3: SHORTS: SUNDAY MAY 8, 2PM PROGRAM 4: FEATURE: SUNDAY, MAY 8, 5 PM

Tickets available at the door for $8

The avant-garde/experimental cinematic form reconfigures traditional narratives and personal experiences, particularly among local subcultures—such as East Village punk, Chinatown markets, Lower East Side rock and roll, and the downtown subversive art and performance scene—creating a parallel between constant evolution of the urban landscape and its inhabitants and the experimental form. We propose to feature avant-garde films from our collection that feature the changing urban landscapes and the people who inhabit them. We’re interweaving the three threads: the urban landscape, the distinct subcultures, and the transformations of the neighborhoods over time, using films from the late 1980s until today.

FEATURING WORKS BY:

Rachel Amodeo Rudolph Burckhardt Bill Brand Donna Cameron

Shirley Clarke Peter Cramer Coleen Fitzgibbons Henry Hills

Philip Hartman & Doris Kornish Ken Jacobs Oona Mekas Marie Menken

Lynne Sachs Joel Schlemowitz MM Serra & Jennifer Reeves Mark Street

LOCATION:

MILLENNIUM FILM WORKSHOP

66 E. 4th St.

(btw. 2nd Ave. and Bowery)

212-673-0090

FOR FURTHER INFO:

Contact: MM Serra

Telephone: 212-267-5665

Email: filmmakerscoop@gmail.com