The Longhand Film

Filmmaker Magazine

by Courtney Stephens

in Issues, Reflections

on Jul 12, 2021

https://filmmakermagazine.com/111927-the-longhand-film/?fbclid=IwAR2_9BPt8O0WR1HnKUGxmoPjgLygDRY5WCFRDYFZEF0192rsotVRArgSpgA#.YQf3e1NKh3T

For the past six years, I sought out amateur travel films made by women in the first half of the 20th century, which I collected in an all-archival essay film, Terra Femme. In the process, I watched dozens of hours of footage of everything under the sun: biblical gardens, women doing laundry, ice fields, a tapir, mounds in a cemetery. Occasionally, there is a handwritten intertitle. “Crossing the Equator” reads one, and the filmmaker has added little serif marks to the letters in “Equator.” What follows is footage shot onboard a boat during a line-crossing ceremony, in which Poseidon and his goons haze anyone crossing for the first time by slathering them in shaving cream and throwing them in a pool—an equatorial baptism. Elsewhere, title cards show up with facts (“Had lunch here”) or bits of acquired wisdom (“Camel wisdom: if you stand behind them, they can’t spit on you, if you stand in front, they can’t kick you.”). By turn spectacular, mundane and cliched, the films also feature hand-drawn maps and shots of signage or tourist pamphlets. The effect is of a moving image scrapbook, annotating journeys through vanished worlds.

With the advent of home movie cameras in the 1920s, products quickly came on the market that allowed amateur filmmakers to make printed intertitles with borders and decorative fonts. Premade title sets were also advertised, a few feet of leader that could be affixed to the head of a film, with stock titles like “Symphony in Color” and instructions on what should be shot—in this case, spring blossoms. Other suggested subjects included airports, auto races, birthday parties and a scenario called “Hold the Phone” in which a housewife has her phone call interrupted by a “child crying, a salesman at the door, a collector, etc.” In contrast to this preordained content (and the predestined activities of female lives), women’s travel films are comparatively anarchic, seemingly driven by an urge to capture chance events, then collate the world according to them, with private notations and other forms of text stitching them together. Their haphazard arrangement and personal touches set them firmly apart from professional travel documentaries of the time. These were not aspirational endeavors, nor were many of the women I researched involved in the (male-dominated) amateur cine-club circuit. These films seem, by and large, to have been private documents, intended for the friends and families of their makers or for the makers themselves.

In his essay “In Defense of Amateur,” Stan Brakhage noted that the word in Latin meant “lover” and wondered why, by 1971 (when he published the piece), it had acquired a derogatory connotation. He extols the dedication of the home-movie maker, who photographs “the events of his happiness and personal importance.” Brakhage sees himself and other experimental practitioners as successors to this tradition. (He is in agreement here with Quentin Tarantino, who once stated, “I like holding on to my amateur status.”). As an experimental film canon took shape in the 1970s and ’80s, filmmakers like Hollis Frampton and Fred Worden used handwriting to call attention to the nature of word and image in a film, and to create palimpsestic studies of the different drafts living inside a finished work in films like Frampton’s Poetic Justice and Worden’s How The Hell I Ripped Jack Goldstein’s Painting In The Elevator. Brakhage himself “signed” many of his films by scratching cursive letters into successive frames of celluloid leader—when projected, the frames write the filmmaker’s signature across the screen in light. In 2021, we have seen the near-elimination of the line between professional and amateur. We use screens to scribble on Instagram stories and dash off memes. But handwriting continues to show up purposefully in experimental and nonfiction films, even as longhand writing becomes increasingly obsolete (cursive is no longer taught in many primary schools). What does handwriting convey when it shows up in a film? What is its relationship to past modes of vernacular writing? How does written text imbue or even subvert the information it conveys?

In The History and Uncertain Future of Handwriting, Anne Trubek points out that early writing was primarily a form of counting. Cave paintings are less works of self-expression, it is believed, than tallies of goods—an early form of data visualization. Many of the Mesopotamian tablets that have survived are receipts, the minuscule marks of ancient cuneiform recording a trade of linen under the rule of a particular king or providing a list of temple holdings. It would be several millennia before the notion of personal handwriting, and the belief that it reveals attributes of the individual, entered the public imagination. For the centuries in between, written scripts operated more like fonts, and the point was to adhere to them. The Romans wrote inscriptions in capitalis, the classically balanced serif script to which, perhaps, the filmmaker makes homage in her embellished “Equator” (and from whence we get the term capital letters). The geographically distinct scripts that proliferated in Europe through the Middle Ages were so ornate they were often unintelligible across regions. They were conformed to diligently by the monks who copied books and manuscripts and, following the advent of the printing press in the 15th century, found themselves in demand as tutors of penmanship. Formal calligraphy had a new application in Europe: the drawing up of documents and bureaucratic papers in the conquest of territories.

The analysis of character through handwriting came about in the 19th century and was briefly linked to the occult and divinatory practices like palmistry. But it gained steam as an empirically tested collection of truths that could bridge science and religion by revealing how the soul shows itself scientifically through writing. These ideas especially took hold in France, where to this day it is common to ask job applicants to provide handwriting samples, which are then analyzed by graphologists, or handwriting experts. Strong-willed people cross their t’s with force; low-hanging g’s and y’s are evidence of sadness. Pioneering graphologist Jean-Hippolyte Michon wrote, “Who can doubt that every word is the spontaneous and immediate translation of thought? And who can doubt that handwriting is as spontaneous and immediate a translation of thought as speech? All handwriting, like all language, is the immediate manifestation of the intimate, intellectual and moral being.” That the written word is the uninterrupted route from self to page is essentially the logic behind the signature, that mark of the unique self that binds us irrevocably to time—to debt, marriage and more. It becomes physical evidence, and this instant memorialization of the moment of writing links the pen to the camera, which can only ever film the present moment.

Handwriting often shows up in fiction films, as when a character reads or writes a letter or makes a written confession, as in Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest. Usually, it is a way of conveying internal emotions to the viewer or simply a means of moving the story forward. In nonfiction filmmaking, it could easily be seen as a neutral technology—just another way of making words, an ornamental flourish. But longhand writing carries with it more than just the information it conveys. In it lies the mystery of the author, a person living and writing in time. While the history of writing calls to mind learned volumes and chiseled inscriptions, and all the forms of perpetuity that humans have sought after, it is conspicuous evidence of frailty and disputation, of the provisional nature of factual knowledge. Authors die or change their minds. Libraries burn. Buildings fall. Ink fades.

Handwriting often shows up in films that feature nudity. In Mona Hatoum’s 1988 epistolary short Measures of Distance, we hear letters read aloud from the filmmaker’s Palestinian mother, exiled in Beirut. Arabic writing is layered upon what we learn are nude pictures of the mother taken by the daughter on a previous trip, before the current war that prevents Mona from returning. The mother’s letters, read aloud, tell of car bombs and the circumspect eye of her husband. She writes, “You asked me in your last letter, if you can use my pictures in your work. Go ahead and use them, and don’t mention a thing about it to your father. You remember how he was shocked when he caught us taking the pictures in the shower during his afternoon nap…. He still nags me about it, as if I had given you something that only belongs to him.” What is illicit in the film are not the naked pictures but the secret intimacy, forged in the text that overlays them. The letters speak to the constraints of female life; the fact of writing is a form of resistance.

In Maryam Tafakory’s short I Have Sinned A Rapturous Sin, made 30 years later, the filmmaker’s arms, but not her face, can be seen writing Farsi in chalk on black fabric. The words are lines from Sin, the poem by Forugh Farrokhzad (who would also direct the immaculate film The House Is Black). The lines, published when the Iranian poet was only 19, describe a bliss found in submission, beginning:

I have sinned a rapturous sin / in a warm enflamed embrace / sinned in a pair of vindictive arms / arms violent and ablaze

As she writes, Tafakory whispers the words aloud in a voice of urgent defiance. English subtitling in the form of cascading typed text fills up pockets of black in the frame, like echoes of the handwritten pleasure. The filmmaker writes me via email, “typed text and handwriting are different voices for me: handwriting is more quiet, a little shy and secretive. often cryptic or blended into the image. it can be dismissed or lost. my handwriting is always in farsi. typed text is more rigid, has a louder and more arrogant tone with fake authority and/or contradictory remarks. my typed text is mostly in english.” The scenes of writing are contrasted with footage of male commentators, offering their own take on female sexual energies: “In order to reduce her lust and unbridled passion, woman should eat lettuce.”

Written text is by its very nature an act of friction. In Goodbye to Language, Jean-Luc Godard’s 3D feature, the author Mary Shelley is depicted writing outdoors, her quill squeaking buoyantly on the page, as if to suggest that the loss of the written word is the loss of a kind of intercourse. Scratching words into celluloid is analogously erotic, like grazing skin with a needle. It’s also incredibly time-consuming. For just a few seconds of a word onscreen, one must carve the same word into hundreds of individual frames of film. The end effect is something coarse and alive. In 1967’s White Calligraphy, Takahiko Iimura carved an entire eighth century Japanese fable into black leader, one character per frame. It is too rapid to read and becomes pure choreography—a flurry of line and curvature. Writing is, after all, a form of drawing, and character languages carry in them earlier modes of representational sketches. In Su Friedrich’s film Gently Down the Stream from 1981, the filmmaker relays a series of dreams she had, interspersed with impressionistic images. “Wander through / large quiet / rooms” read the first three frames, in what appears to be liquid chalk but is revealed to be inscription on the film itself. The shifting allography (ways of making letters) suggests the mutability of dream space, in which one is some sense both writer and reader. The text HOWLS in sharp capitals when a woman cries out or gets tidy and nearly translucent when another shivers. From the handwriting analysis perspective, is variation the equivalent of the soul engaging in open play? An old book on handwriting analysis says that the letter t alone can tell you a lot about a person. A high t means you’re vain, a looped cursive t means you’re sensitive, a low stem on the looped t means you’re sensitive, but you try not to show it. Try to be less sensitive, the book advises. But the film is uninterested in this kind of external analysis. The self is a conjurer. When the dreamer makes a second vagina next to her first one, she wonders: Which is the original?

As a viewer, waiting for words in the frame causes a shift in the images. In Friedrich’s film, highlights on the surface of a pool start to look like letters attempting to form, which also carries an edging, erotic charge. “I lie in a gutter giving birth to myself,” the text finally declares. In the films of Nazlı Dinçel, hand-scratching (and typing, and hammer-punching) agitates the surface of explicit images as a way of claiming them. In her series of “Private Acts” films, the filmmaker recalls forbidden scenes: early experiences masturbating with a showerhead and other forms of autoeroticism, first sex following a divorce. These recollections are scratched into haptic imagery—the thumbing of a flower stamen is as charged as the jerking off of an anonymous penis—firmly imposing her own articulation of events upon tender scenes, an act against shame.

In another scene from Goodbye to Language, a voice asks from offscreen, “To live one’s life? Or to tell it?” The line is quoted by Moyra Davey in her 2016 video Hemlock Forest. Davey says that when she asked her son if he keeps a diary, he replied that he’d rather live his life than narrate it. Handwritten ruptures threaten to destabilize the image, to force time into review even as it unfolds. But they also open the frame to a different kind of truth-telling, which comes from earned knowledge and intellectual itinerancy. They are interested in what gathers over time, similar to a coral reef or the marked-up margins of a book. Language time differs from visual time because what is written has already happened, has been experienced, processed and transformed into words. Handwriting adds to this the accumulated time of the physical being, beginning with the years it took the child to learn to write.

Films use handwriting to summon the pasts that lie dormant in the present, not only for individuals, but within the physical landscape. Hope Tucker’s The Sea [Is Still] Around Us is what the filmmaker calls a salvage ethnography. The 2012 short film uses postcards sent from Corinna, Maine, over the course of the 20th century. The text is laid over contemporary shots of Corinna’s buildings and landscapes while Tucker’s quivering hand holds the postcard itself in the frame, showing earlier versions of the contemporary places. The chronology of postcards describe decades of industrial exploitation, starting with fragments of text from the years before the mill came—“I have a dandy tan on”—which give way to descriptions of choked waterways and overdevelopment. What began as handwritten messages transitions to typewritten text. One can’t be sure if this mirrors what is on the back of the cards we are shown, but the switch is clearly meant to suggest the same mechanization imposed upon the land.

Longhand is the mark of the living human; mechanical type is the mark of The Man. It is near-consensus among historians of type that something was lost in the transition to networked writing systems—not only in the loss of intimacy between the writer and the word, but the loss of intimacy found in vernacular modes of writing such as the postcard, with its shorthand convivialities. “Aloha!” reads a postcard from Hawaii sent in 1961 (and acquired by me at a thrift store a half-century later). “Mickey Rooney stayed here while visiting Honolulu. Most of the movie actors and actresses stayed here. Warm today 80 degrees. Looks like rain but when it rains it lasts about five minutes. Just a drizzle. Liquid sunshine. Los Angeles tomorrow.”

But then tragedy falls into our lives: A loss, an illness, a pandemic interrupts the route we were on, remapping our geographies. All proximities become personal. In Instructions on Parting (2018), the filmmaker and artist Amy Jenkins documents a period in her life during which, in rapid succession, she became pregnant, then lost her sister, her mother and her brother, all to cancer, in a matter of a few years. The intensities of this time period are punctuated with notes of handwritten grief, stated frankly, ellipses between locations during an intense series of transits between dying family members in an endless succession of final visits. What can be told to the page is different than what can be spoken aloud, and this holds true of spoken voiceover.

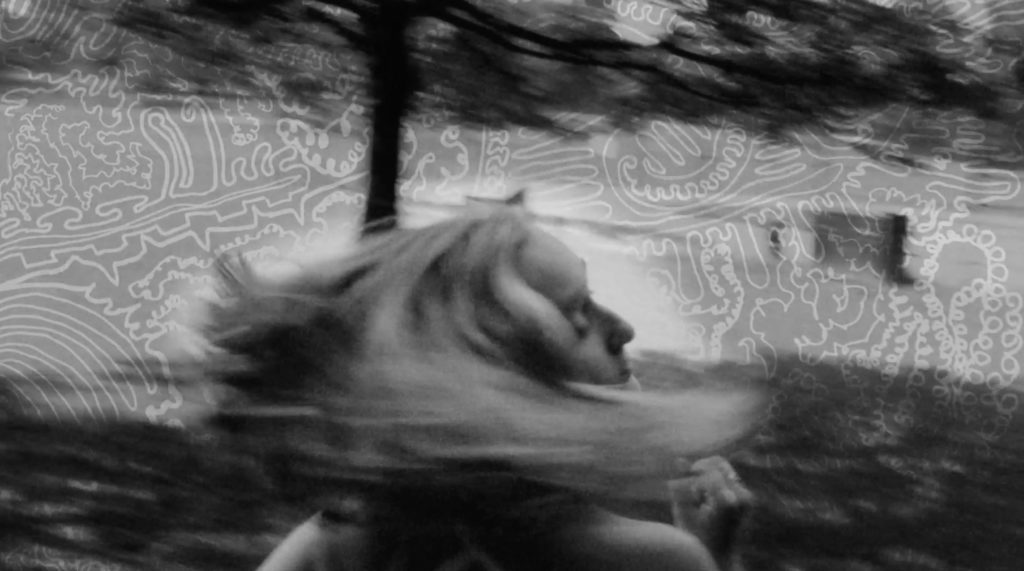

In 2017’s Tip of My Tongue, Lynne Sachs, on the event of her half-century birthday, gathers people born the same year but from other parts of the world, to think through the major historical events of the past 50 years as refracted through place and perspective. The film opens with a sequence of notations scanned from notebooks. Jotting and crossed-out phrases alight on the screen, then burn out like coals in time. They echo the feeling of living through historic events, when what is happening feels too fast to ever quite grasp except in retrospect. Plato wrote that written words can do nothing more than remind one of what one already knows or has already experienced, and the film is an homage to orality, the idea of writing as a prompt for performance and dialogue. As Socrates quipped, “If you ask a piece of writing a question, it remains silent.”

Baseball marginalia from James Benning’s private collection are linked to the diary of a would-be assassin in American Dreams: Lost and Found (1984), an iconographic exploration of the American social landscape. The scrolling cursive text at the bottom of the screen belongs to the diaries of Arthur Bremer, who, intent on shooting president Nixon, found an easier target in Democratic candidate George Wallace (Wallace survived). Hank Aaron memorabilia are presented in the upper quadrant of the frame, while the soundtrack offers key audio from the era: “You don’t have Nixon to kick around anymore,” advertising jingles, news coverage, rock ballads. This approach of multivalence through ephemera has the effect of being both lovingly culled and openly incomplete, acknowledging its own limits through the sheer specificity of what has been chosen for inclusion. We get the contours of a subtractive intelligence, collating debris and sifting through transmissions, striving not for completion but for insight. Benning’s cursive hand shows up again in 1992’s North on Evers. This time, it’s his own diaries that scroll over the physical landscape, often disappearing behind darker patches in the frame, then reemerging over grass or a window, like thoughts that dip into the arcane and return unfazed. He visits some friends in San Antonio. “They have a four year old daughter,” the words announce over sand. “I like kids at that age. They want to learn so bad.”

A figure walks through what appears to be a smoldering forest in Sky Hopinka’s Fainting Spells (2018), whose form makes homage to Benning. The film is an imagined conversation between someone younger asking someone older to tell them the story of how the ho-chunk began using the Xąwįska (Indian pipe plant) to revive people who have fainted. Text scrolls across land and sky, though maybe this terrain is less a place, like Benning’s America, than a substrate upon which knowledge is remembered:

“Night is falling and the spirits can see us. / It’s time to go home. / You had told me, ‘When you see the red / oaks, follow the water. / Then, when you find a fork in the river there / will be a lovely piece of land. / Remove everything that shines from your / hands, from your neck, from your body, and / swim to the nearest shore.’ / Xąwsįska, you’ve fainted again.”

Magnetic poles determine the earth’s latitude lines and the equator, but lines of longitude are a human invention, drawn onto the earth arbitrarily. A conference to decide where to place the Prime Meridian took place in 1884, at which representatives from several nations (the colonizing ones) met in Washington, D.C., to agree upon a common zero longitude line. Each nation had used its own navigation for maritime maps—on French maps, deviations of longitude were measured from Paris and so on. But the equally essential point of the conference was to standardize time zones so that clocks around the world would sync. At the time in America, neighboring cities sometimes had different times of day, making train schedules rather complicated. The record of the conference attendees vying for a longitude zero that centered themselves reads a bit like a Monty Python script. The delegate of France shoots down the British delegate’s pretext for a longitude zero cutting through Greenwich, England (that the British Empire had the largest tonnage of world shipping), as “entirely devoid of any claim on the impartial solicitude of science.” In other words, it would simply be a flex on the part of Great Britain. The conference adjourns with Greenwich as longitude zero, initiating Greenwich mean time. One imagines the world’s globe-makers updating their globes, drawing the longitude lines on by hand. Imperial perspective has been subsumed into the appearance of objectivity. Writing in its earliest form: a transaction receipt.

In Kevin Jerome Everson’s short film Partial Differential Equation (2020), a college student fills a chalkboard with a long mathematical proof. Differential equations include a changing, unknown variable, often stemming from the physical world. What is the force on the object? Where is it going? Partial differential equations are concerned with the multiplicity of factors at play in a given situation: position, temperature, orientation. These variables can end up encompassing almost everything, and solutions can blow up to infinity as they evolve in time, becoming unsolvable. We never learn what is being represented in the equation on the chalkboard. It takes more than eight minutes to write it out, filling the chalkboard (but safely by the end of the 16mm reel).

Those who read in languages that move left to right on the page, like English, tend to experience screen motion the same way: a car driving toward screen right has the sense of forward momentum and progress. Movement toward screen left is going somewhere else, as in Behrouz Rae’s short film Untitled. When the filmmaker draws a line in pencil “backward” across a world map in a book labeled Retreat of Colonialism in the Postwar Period, he charts his own path from his native Iran to his adopted home, the United States. Mapmaking is a way humans assert control over the physical world. Like the drawing up of contracts, it was an essential tactic of imperialism. Drawing one’s own path into an atlas, or making a moving image version of one, is an alternate form of mapmaking. Both add another variable to the two-dimensionality of the map—the variable of time. The use of handwritten language in non-narrative cinema is similar. Language, in these genres, is often used to deliver facts and information, which are supposed to have no point of view. But by including their own written hand, the filmmaker uses these tools as a means of finding out what the filmmaker themself knows, embracing the infinite contingencies that have acted upon them, and which may even be encoded in their handwriting. I find my own to be inconsistent; the graphology book tells me that variability is the result of a desire for change.

“One day, time will make every road map in the known universe obsolete and useless. And then we’ll all get lost,” says Bill Brown in his short documentary Roswell (1994), filmed on desert roads in and around New Mexico. Brown isn’t so much interested in whether a UFO crashed in Roswell in 1947 as he is in the burden of space and time that acts upon those on earth. What must it have been like for that UFO captain, navigating above the big blank desert without a map? Phrases of spoken voiceover are occasionally scrawled in strong Sharpie letters in the filmmaker’s “secret diary”: “ON THE ROAD TO CORONA I REMEMBERED (the page is turned) A REALLY SAD STORY…” A solitary woman, living out on the land during pioneer days, would write love letters, then release them into the open wind. The narrator speculates that one of these letters reached an alien starboy, who came to New Mexico looking for her. Maybe, he speculates, the Roswell crash is less a terrestrial mystery than a cosmic tragedy: the story of a woman who almost had the chance to outrun her own fate by vanishing in a UFO. A woman who, through desperation or optimism, wrote tender greetings into a void—to no one in particular.